Alan Matthews discusses the agri sector’s medium term future

The agricultural sector is recovering. However, dependence on direct payments, climate change and ageing farmers are potential problems, writes Alan Matthews.

Irish farming and the food industry is on a roll. Following a disastrous year in 2009 when milk prices collapsed, the farming industry has seen two good years when incomes have recovered by 70 per cent from that dreadful experience, although they still remain below the levels reached in 2005 and 2007.

Is the optimism justified? There are some grounds for thinking so, but also some reasons not to overdo the hype.

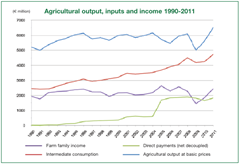

To evaluate where we are in farming, it is useful to provide some historical context. The chart shows trends in the value of agricultural output, inputs, direct payments and farm income since 1990.

The most striking thing about the trend in the value of agricultural output (measured at basic prices, which includes the value of any coupled payments or premia linked to the output a farmer produces) is that, following some growth in the early 1990s, it has basically stagnated since then.

At the same time, expenditure on agricultural inputs has steadily increased, partly due to greater volumes but also to higher prices.

Throughout the period, farm incomes have remained static (again, with the exception of the dip in 2009). The chart underlines the importance to farm income of the decoupled income payments which were introduced as part of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy in 2005.

In a normal year, around 70 per cent of farm income is accounted for by these direct payments, but in 2009 there would have been a negative farm income for the country as a whole were it not for these payments.

The chart does not suggest that the recent rise in farm incomes has been out of the ordinary, but rather a recovery from the depression in 2009. Indeed, Teagasc economists, in their January 2012 situation and outlook, have projected that the value of family farm income will fall back by around 12 per cent this year.

The longer-term optimism in farming derives from two factors. One is the medium-term outlook for continued high global and EU food prices, in part linked to higher energy prices and the growth in demand for biofuels. The 25 per cent increase in cattle prices in Ireland in the past year is one example of this trend.

The downside of high output prices is that input prices are rising even faster, so that farmers experience a deterioration in their terms of trade.

The second factor is the expected removal of milk quotas in 2015. Gross margins per hectare in dairying are well above those available in alternative enterprises, so the prospect of the final removal of quotas allowing dairy farmers to expand production without constraint opens huge opportunities. The Food Harvest 2020 report projected a possible increase in milk output of 50 per cent between 2007-2009 and 2020.

These positives are vulnerable to a number of potential threats. For much of the first decade of the 2000s, what worried farmers most was further trade liberalisation as a result of a successful conclusion of the Doha Round. This would have meant the abolition of export subsidies, a significant overall reduction in average tariff protection for beef and dairy products, and tighter ceilings on overall production-linked support.

The Doha Round no longer looks likely to happen in the near future. Successive CAP reforms and higher global food prices have made the prospect of third country competition much less daunting. Even bilateral trade deals, such as the free trade agreement with Mercosur, which so concerned Irish beef farmers, now seem much less threatening.

A more immediate threat is the outcome of the current EU negotiations on the size and composition of the EU budget over the period 2014-2020 and, linked to that, the discussions on the review of the CAP post-2013.

The initial Commission proposal for the budget was very favourable from an Irish perspective. The Commission proposed maintaining the CAP budget constant in nominal terms, in the context of a slight increase in overall EU spending.

However, many of the net contributor member states are unhappy with this proposal. Given the climate of fiscal rectitude in Europe, the budget outcome may not be so favourable to Ireland, thus reducing the future flow of direct payments.

The issue for the Agriculture Commissioner in the budget negotiations has been how to justify the large share of the overall EU budget (around 40 per cent) still being spent on agriculture. His answer is to green the payments, by linking a proportion of the payment to compliance by farmers with a series of environmentally desirable practices such as setting aside a minimum proportion of each arable farm as an ecological focus area, maintaining existing areas of permanent pasture, and requiring crop diversification on arable farms.

Compliance with these criteria will not be unduly onerous for Irish agriculture although some tillage farms in the south-east of the country could face higher costs. Of greater political concern to Irish farm leaders is the proposal that payments within each country or region should move to a flat uniform rate.

When Ireland decoupled direct payments from production in 2005, it did so using the historic model which meant that the differences in payments received by individual famers were set in stone. Some farmers received high payments per hectare because of the particular farm system and level of production on their farms in 2000-2002; a few farms receive nothing at all.

In general, payments are higher in the south and east of the country compared to the west and north. While some regionalisation of the level of payments would be allowed under the Commission’s proposals, the fear is that the redistribution of payments would penalise the more productive farms and shift these payments to less productive farms.

In the long-run, high direct payments drive up land prices, making the cost of entering farming (for young farmers) or expanding (for enterprising farmers) extraordinarily expensive. Over time, a gradual reduction in the untargeted, across-the board payment would encourage necessary structural change and allow more efficient farmers to manage a higher proportion of the available land.

Another potential conflict looms with climate policy. Agriculture is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 40 per cent of total emissions from the non-ETS sector. As part of the EU’s climate strategy, Ireland has stringent annual emission targets to meet after 2014 to 2020 and beyond.

The relevant ministers have stated that food production will not be constrained by climate targets, but exceeding these targets will either require the state to purchase surplus emission credits from other member states, or face fines.

Structural issues particularly around access to and use of land may also prove a constraint on increasing output.

Less than 7 per cent of Irish farmers are under 35 years of age, and 45 per cent are over 55. While this demographic structure has characterised Irish farming for some time, it is an unpromising basis as a platform to launch a major increase in output.

Thus there are promising opportunities for Irish farming in the future, but these opportunities should be evaluated realistically. The lessons of the past are that sudden changes in the trajectory of farm output and incomes are unlikely.

Alan Matthews is Professor Emeritus of European Agricultural Policy at Trinity College Dublin