Irish-English explained

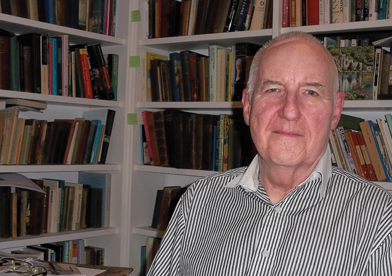

Professor Terence Dolan, who has just completed a third edition of his Hiberno-English dictionary, discusses the way Irish people use the English language with Stephen Dineen.

Professor Terence Dolan, who has just completed a third edition of his Hiberno-English dictionary, discusses the way Irish people use the English language with Stephen Dineen.

For Terence Dolan, an expert of Hiberno-English for over thirty years, the distinctly Irish use of English is alive, well and changing. “One reason I write this stuff on Hiberno-English,” explains Dolan, “is I’m trying to celebrate the Irish use of English, to give it a full grammatical pedigree and to show how it’s used throughout the country and other places too.”

Dolan says there are three main components to Hiberno-English: the spoken word’s grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. The grammar is based on the Irish language. “There’s no have in Irish, so you can’t say ‘I have written the book’ in Irish,” he explains, hence the Hiberno-English: ‘I’m after writing the books’. Translated grammar (from Irish) is the source of and being used instead of while in certain sentences e.g. ‘He came in and me having my dinner.’

The Hiberno-English vocabulary is vast. Words and phrases include: eejit, phoney, pass-remarkable, cuala-buala. Craic is an example of a conservative, old fashioned word from 17th century English settlers in Ireland, and “nothing whatever to do with Ireland at all,” says Dolan. It derives from the Anglo-Saxon cracia, meaning to make an explosive noise to entertain your friends.

Hiberno-English pronunciation of English words has distinct traits such as an embellished ‘h’ in words with ‘th’ like Thomas (because there is no ‘th’ in Irish), and the epenthetic vowel, “which is an extra vowel put in between r and m,” e.g. farim, worim, filim (phoenetic spellings).

Written English is universal, however. “Written is standard because language has to be like traffic lights, with red lights and green lights,” Dolan tells eolas. Everyone has the same rules to ensure “universal acceptance and understanding.”

“The great thing about Hiberno-English,” explains Dolan, “is it is a distillation of the Irish character.” He says we often speak in code and people from rural areas can be very oblique. “Irish people over the centuries have been oppressed, so therefore they don’t want people to know what it is they’re thinking or saying.” Irish politicians utilise Hiberno-English “because it’s devious to start with, and evasive, so politicians naturally will use that language when they’re speaking English.”

Dolan says politicians “love using big words, pompous words like ‘challenge’ all the time.” He explains: “Challenge actually doesn’t mean what they think it means (i.e. to compete about something).” Instead of speaking about difficult times, politicians use: ‘These times are challenging’. He says politicians feel it gives them “a certain prestige.”

Dolan has noticed that “there are far fewer rural phenomena now or ecclesiastical phenomena” in the vocabulary. “You used to have lots of references to Christ and the Virgin Mary over the centuries because of the Catholic power in Irish society. There’s been quite a few omissions now,” he notes. “As rural communities suffer in Ireland, and they become less powerful and less dominant, a politician will want to speak in the style and culture as it’s evolving.”

Recent phenomena in Hiberno-English’s evolution include “D4 English”, developed by “upwardly mobile people” who “began to think that language and the way you speak is a stylistic accessory.” Irish immigration may have influenced the London cockney language, says Dolan, who is originally from London but of Cavan parents, and has been living in Ireland since 1970. The cockney rhyming slang was possibly invented by the Irish “so the actual English wouldn’t understand what they were talking about.”

Foreign people and immigrants inIreland often find Hiberno-English incomprehensible, Dolan notes. Foreign people tell him Irish people speak “so fast”, and that they have difficulties with rural Irish accents. This is particularly difficult for non-Irish people who have been taught standard English grammar, only to experience the “strange oral grammar” of phrases like ‘I’m after doing’ and ‘the week that’s in it’.

Beyond Ireland, English is changing as “more and more people are listening in to world news so they need to be part of the jargon empire as it now is.” American English is dominant and English is changing through its “sheer power”. Dolan explains: “A thousand million people speak English every day, and English itself has one million words in its vocabulary. It’s enormous. And therefore so flexible.”

Abbreviation is becoming more common but this is not new. Whilst researching a book he is writing on Richard FitzRalph, a 14th century Archbishop of Armagh and Oxford University Vice-Chancellor, he discovered that FitzRalph’s Latin texts were full of abbreviations, explained he believes by the shortage of vellum on which to write. Modern abbreviation in mobile phone texting “is in fact just a follow-on through from something that’s happened 600 years ago.”

In his descriptions of Hiberno-English, Dolan never says it is grammatically wrong. “It’s actually translated English. It’s not bad, it’s very conservative, it’s just got quite a few old-fashioned words,” he explains. It continues to grow and the new edition of his dictionary (to be published in the autumn) will have new words and phrases like NAMA, dig-out and Galway tent, which have become common parlance.

Hiberno-English will take new turns, he predicts, slowly becoming more Americanised. With the increased influence of China in the world: “I think more and more people will begin to speak a Chinese type of Hiberno-English.” How will it manifest itself? “I’ve no idea yet. That’s the future.”

Journey of a language

The way Irish people speak English dates back to 1650s English, according to Dolan, when Irish people had to learn the language “in order to get the instruction from their owners…the lords and ladies of the big castles.” Because their mother tongue was still Irish, learnt English with Irish pronunciation made it a very different form of the language. The pronunciation system of the Irish language was used with the vocabulary of English and Irish together. With the founding of Trinity College (1592), St Patrick’s College Maynooth (1795) and the national school system (1831), English gradually became the norm. The Irish language declined significantly with the Great Famine (1845-48), and English became the language of commerce and politics thereafter.

Hiberno-English was also influenced by Latin through the hedge schools (of the 18th and 19th century). An example of its influence today is the way Irish people pronounce the word data.