Accelerating marine power

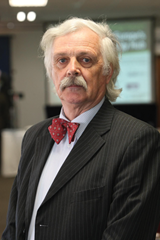

Immediate action to fast-track ocean energy is needed to reach Ireland’s 500MW target, according to Tony Lewis. The UCC professor discusses the problems and potential solutions for the sector with Owen McQuade.

Immediate action to fast-track ocean energy is needed to reach Ireland’s 500MW target, according to Tony Lewis. The UCC professor discusses the problems and potential solutions for the sector with Owen McQuade.

The Government must fast-track marine licensing if Ireland is to generate 500MW from ocean energy by 2020, says Professor Tony Lewis. The University College Cork academic leads its Hydraulics and Maritime Research Centre.

“I think at this point in time it would be difficult to believe that it will happen,” he said of the target. “We really have no strong commitment from the Government to fast-track all of this. There’s great aspirations made but the licensing process is really not put together at this point in time.”

Northern Ireland is more advanced than the Republic on licensing. Consultation is under way and he expects licences for tidal development off the North Coast to be granted by the end of the year.

In contrast, responsibility for marine affairs in the South has been moved between departments and legislation to update the licensing system did not get through the last session of Dáil Éireann. Lewis points out that Ireland is legally bound to have 79MW by 2020, under the National Renewable Action Plan submitted to the EU. As for the 500MW figure, he thinks achieving that by 2025 is a “more realistic target”.

Lewis also sits on the board of the European Ocean Energy Association (EU-OEA) and has been working in the field for over 30 years.

Taking stock of the industry’s status, he sees wave energy and tidal stream as the two areas where the most development is taking place, but both are still at the advanced demonstration level and “not yet ready for commercial deployment.”

This is true for companies across the sector, whether Wavebob in Ireland, Pelamis in Scotland or Ocean Power Technologies (OPT) in the USA: “They’re all the stage where they’re doing commercial development and demonstrations in the sea but I reckon it will be at best 2013 or 2014 before we start to see commercial devices being available for exploitation.” Lewis expects to see the installation of multiple devices by 2015.

However, companies have previously oversold their products, which has damaged the sector’s reputation. Three Pelamis machines were sold to set up the world’s first ‘wave farm’ at Aguçadoura, off Portugal, in 2006, which was subsequently abandoned as they did not meet the stated capacity.

He explains: “The reason is because the small companies are the people who are developing the technologies and they want to go straight into the sea. And you can’t do that so you’ve got to have a risk reduction as you go forward.”

These failures mean that larger companies are reluctant to invest, although some are taking an interest. Examples include the Voith and Siemens joint venture (now Voith Hydro) and Tonn Energy, a joint venture between Vattenfall and Wavebob (of which Vattenfall has a 51% stake). Bord Gáis, EDF and French defence contractor DCNS are also involved.

The Cork centre suggests a five-stage development protocol, which is the norm in major energy firms such as Shell. The International Energy Agency and US Department of Energy concur.

Investment, he expects, will increase over the coming years. Indeed, it is essential to meet the binding targets set down in the European Strategic Energy Technology plan i.e. reduce the greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent, increase the share of renewable energy to 20 per cent and make a 20 per cent improvement in energy efficiency, all by 2020.

However, he points out that the European Commission “can only put so much into research”. National governments and the private sector must also play their part.

However, he points out that the European Commission “can only put so much into research”. National governments and the private sector must also play their part.

The critical grid

Slow progress on licensing legislation, as explained, has been an obstacle but other hurdles include grid availability, technology selection, reliability and Ireland’s capacity to grow the sector.

Further development cannot take place without a “very critical” investment to strengthen the west of Ireland’s traditionally weak grid. The Grid25 plan allows for this in County Clare, around Belmullet and in the south west but it is not yet clear whether this work will be a priority.

The research centre has suggested an undersea cable to Moneypoint, which could then be linked to the 400KW cross- country transmission line. The Marine Renewable Industry Association, he notes, is prioritising development off Clare and North Kerry, which could therefore be ‘cabled’ to Moneypoint.

Marine research across Ireland has been joined up and its funding matches the staged development process.

SEAI’s Ocean Energy Development Unit is “funding companies to develop technology but they won’t fund them to develop technology in Galway, for example, until they finish tank testing in Cork. And similarly, they won’t let them go with grant aid into the open sea until they’ve been through the earlier stages.”

That said, at least 25 technologies are currently available with more on the way, especially in wave. Offshore wind and tidal are relatively straightforward, by comparison, as they depend on turbines.

Simpler concepts are better, in his view. “The complicated devices in theory have the best potential to make good efficiency and everything else but they don’t work independently,” he says, adding that their movement must be constantly controlled for these to operate safely.

“[With] some of the simpler technologies like the OE [Ocean Energy] buoy, which is just a simple box with air pumping in and out, or the Wave Dragon, which is a big box over-topping when it’s full, I think they have the potential in the short term to be the more successful,” Lewis comments. In the longer term, though, the Wavebob and Pelamis devices will potentially be more efficient and cost-effective.

“What we need at this point in time is long-term deployments at sea. I mean, nobody’s been at sea for more than a year,” he contends. An aircraft, for example, must be thoroughly tested before it enters service and the same is true for generators.

In summary, his advice is to walk before you run: “We need more R&D demonstrations rather than commercial demonstrations. We’re still at that early stage of development and once you have deployments, then you can build with confidence, not oversell things and then end up with a big setback.”

Maintenance

As with any other generator, an offshore plant will need maintenance throughout its working life.

Most offshore operators say that they can only carry out that work when the wave height is less than one metre. At Belmullet, though, that only happens over 2 per cent of the year (i.e. seven days or 150 hours) and usually in summer.

Some companies have started to use helicopters for maintenance, as happens in the North Sea oil and gas industry, but Lewis sees problems ahead: “When you’re producing oil and gas, the daily production is more than able to pay for that type of operation but I think the daily production of el

ectricity from waves is not going to be able to support that.”

Ireland’s marine development also needs manufacturing. While a good shipyard is available in Belfast, where Harland and Wolff now assembles turbines, those facilities are limited in Cork and almost non-existent in Limerick.

“Can we really build these things here?” he asks “And do we have the supply chain on the engineering side to actually support all these developments?”

“Can we really build these things here?” he asks “And do we have the supply chain on the engineering side to actually support all these developments?”

And he warned: “Unless we start doing that now, we’re not going to get there and like the wind, we’ll be buying it from Denmark or we’ll be buying it from somebody else.”

Having published his first wave energy paper in Technology Ireland magazine back in 1977, Lewis finds that “it’s been a long time coming” but the time for action is very much now. Ocean energy offers both the potential for jobs and a potential solution for security of supply, which will become one of Ireland’s key policy issues.

“We’re at the end of the pipe,” as he puts it, and energy is taken for granted. The population expects: “Press the button and the lights come on.” A major disruption, though, would challenge that complacency.

One of ocean energy’s big advantages, he concludes, is financial as the fuel is free. “If you pay for it [the plant] now, you’ve paid for it and you know how much it is,” Lewis remarks, whereas with other technologies, “you don’t know what the fuel prices are going to be in 10 years’ time.”

Profile: Dr Tony Lewis

Originally from Llanelli in Wales, Tony Lewis has degrees in civil engineering and oceanography, and came to Ireland in 1975, to start University College Cork’s ocean engineering course. He is currently Professor of Energy Engineering at UCC and Director of its Hydraulics and Maritime Research Centre, the only facility in the Republic for tank testing hydraulic devices.