Electricity in Ireland: a brief history (1916-2015)

Brian Ó Gallachóir, lecturer at the University College Cork and Principal Investigator of Energy Policy and Modelling Research in the university’s Environmental Research Institute, provides a brief analysis of developments within the Irish electricity industry over the past century.

Ireland’s electricity industry had been in operation for more than 40 years before the first nationwide electricity market was established in 1927. Starting small and primarily based around Dublin, local authorities and private companies generated and supplied electricity. In the early 1900s, locally generated electricity spread across Ireland to the main municipalities. During the First World War when coal rations were implemented, a paradigm shift in electricity generation occurred when the British Board of Trade investigated all indigenous sources of energy in the UK. During this period, plans to generate energy from large-scale hydroelectric plants located on Ireland’s waterways were presented. One such proposal played a defining role in the development of Ireland’s electricity sector; harnessing the River Shannon.

Ireland’s electricity industry had been in operation for more than 40 years before the first nationwide electricity market was established in 1927. Starting small and primarily based around Dublin, local authorities and private companies generated and supplied electricity. In the early 1900s, locally generated electricity spread across Ireland to the main municipalities. During the First World War when coal rations were implemented, a paradigm shift in electricity generation occurred when the British Board of Trade investigated all indigenous sources of energy in the UK. During this period, plans to generate energy from large-scale hydroelectric plants located on Ireland’s waterways were presented. One such proposal played a defining role in the development of Ireland’s electricity sector; harnessing the River Shannon.

Harnessing the energy of Ireland’s longest river, the Shannon, was one of the first major developments of the newly formed Irish Free State. Spear-headed by Irish engineer Thomas McLaughlin, the Shannon hydroelectric scheme utilised a 30-metre head height on the river to deliver 85MW of electrical output and included plans for a supply network to distribute the electricity nationwide. Once commissioned, the Shannon hydroelectric plant (referred to as Ardnacrusha due to its geographical proximity) was adequately sized to meet the entire national electricity demand in its early years of operation and to make Ireland’s electricity sector 100 per cent renewable.

Ireland’s newly formed first Government decided to establish the State-owned Electricity Supply Board (ESB) in 1927 to operate, manage and maintain the Shannon scheme and distribute the electricity countrywide. The ESB turned down the option to sell electricity in bulk to other distributors, instead opted to deliver directly to consumers on a non-profit-making basis. This decision was made on the basis that local politics and municipal boundaries should not hamper the development of a national electricity network according to Shiel (1984).

Once Ardnacrusha was commissioned in 1929, the ESB had a transmission and distribution network (110/38kV) ready to transfer electricity nationwide. Over the following decade, generation capacity increased, becoming more fuel diversified and geographically dispersed. New hydroelectric plants were commissioned and peat was considered as an alternative fuel source for electricity generation in parallel with the pursuance of rural electrification policies. With coal rationed again in the Second World War, peat was promoted as a viable alternative; one that included the benefits of being indigenous, widely available and, from a socio-economic point of view, advantageous to rural Ireland. Rural electrification was delayed during this period of unrest and it was not until the Rural Electrification Scheme (1946) and the Electricity Supply Amendment Act (1955) were passed that the electricity network started to reach the most rural and isolated communities in the country.

By 1970, 46 per cent of Ireland’s installed generation capacity was indigenous (peat and hydro) and 54 per cent oil-based. With more oil-fired units in planning, and yet devoid of any indigenous oil resources, this level of dependency left Ireland in an exposed position for both oil crises in the 1970s. However, as pointed out by Manning and McDowell (1984), early warnings from the ESB were brought to the attention of the Government surrounding the risk exposure from over-reliance on a limited number of sources for electricity generation.

Initially, the concerns related to hydro and peat but later, in the 1960s, these changed to oil. Concerns proved correct in both instances as hydro and peat generation experienced difficulty in 1958/59 and 1963/64 due to weather conditions which restricted their capacity to generate electricity and in the late 1960s/70s, oil was affected by multiple events such as the Six Days War (1967), the cutting of the Trans-Arab pipeline (1970) and the 1970s oil crises. It was not until a series of events in the 1970s that energy policy in Ireland became focused and began to shape the electricity sector for years to come according to FitzGerald et al. (2005). Firstly, the oil crises proved to the Government that over-dependence on a single fuel source, especially a non-indigenous fuel susceptible to geopolitical instability, heightened risk exposure. Secondly, natural gas of commercial quantity was found off the south coast in 1973; and thirdly, nuclear power became an option for providing base load power.

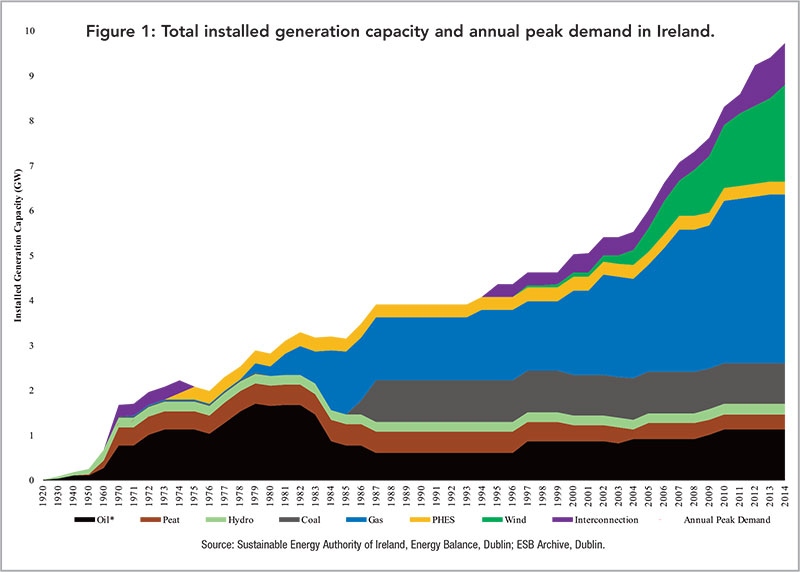

Alternatives to oil-based electricity generation were examined to address concerns surrounding the nation’s over-dependency. Over this period, gas generation became more widely used. This stemmed from the newly developed indigenous gas resource along with advancements in gas combustion technology many oil-fired units were retrofitted to gas while new peat units were also commissioned for security of supply reasons. Studies carried out at the time showed that nuclear power was the only serious alternative to oil for providing base load power in Ireland per Manning and McDowell (1984), however issues surrounding size of the plant were an initial barrier followed by environmental concerns which quickly prompted a negative public perspective towards the Carnsore Point project. Due to an accumulation of issues the project was shelved in favour of a coal-fired plant in Moneypoint, County Clare. Commissioned between 1985-1987, Moneypoint added 915MW of generation capacity at a time when the economy was performing poorly, leading to large over capacity on the system, as shown in Figure 1.

The sector continued to develop and further diversify throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century. The history of modern-day wind power in Ireland is an example of this development when it began with the first major demonstration project at Bellacorick, County Mayo. The project, funded through European Commission under the VALOREN programme, contained 21 Nordtank turbines with a combined capacity of 6.45MW. Through focused, strong energy policy over the following three decades, Ireland’s wind power industry grew significantly. At the end of 2015, the installed wind power capacity in Ireland was 2455MW per the International Energy Agency (2015), producing the third highest contribution to national electricity demand (22.8 per cent) of all IEA Wind Member Countries.

For further details on the electricity sector development in Ireland and the various policy decisions that sculpted the industry over the last century, see A 100-year review of electricity policy in Ireland (1916-2015), Energy Policy 105 (2017) 67-79, available at ScienceDirect.com.