An Irish political Moses

March 2018 marked the centenary of the death of John Redmond. In recent years, a concerted effort has been made to rehabilitate the legacy of one of the most influential constitutional figures of 20th century Ireland. DCU’s Daithí Ó Corráin explores his life.

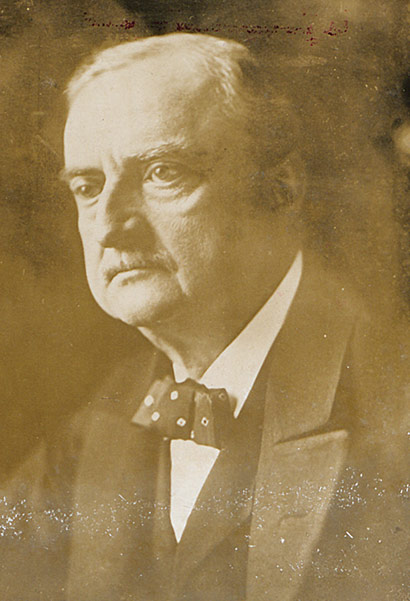

Few Irish political careers can rival the extremes of success and failure experienced by John Redmond. Weary and disillusioned, he died of heart failure on 6 March 1918 at the age of just 61. One British newspaper depicted him as a political Moses doomed to wander in the desert for 40 years with only a tantalising glimpse of the Promised Land. That, of course, was Irish home rule and in 1914, Redmond, as chairman of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), was expected to become the first Prime Minister of an Irish home rule parliament. Unfortunately for Redmond, high office was denied to him as the depth of unionist opposition to home rule and the timing of the outbreak of the First World War contributed to a very different historical trajectory. After the 1916 Rising, a demand for an independent Irish republic, championed by Sinn Féin and the rising generation, swept aside home rule. Redmond’s final years had the pathos of a great tragedy as he lost not only his cause but his following.

In his graveside oration at Redmond’s burial in Wexford, John Dillon, his deputy and successor, suggested that, “[t]ime will do justice to his work and to his statesmanship (hear, hear), and all the people of Ireland, even those who today misunderstand him, will in time come understand the greatness of his life and of his work and of the unselfishness of his career.” A reappraisal of Redmond’s life and legacy has taken decades. Although Denis Gwynn published his sympathetic The life of John Redmond in 1932, remarkably a fresh and sustained biographical treatment did not appear until Dermot Meleady’s fine two-volume biography in 2008 and 2014. On the centenary of Redmond’s death, the appearance of three studies – Pat McCarthy, The Redmonds and Waterford: a political dynasty, 1891-1952; Alvin Jackson, Judging Redmond and Carson; and John Redmond: selected letters and memoranda, 1880–1918 edited by Dermot Meleady – finally satisfied Dillon’s exhortation.

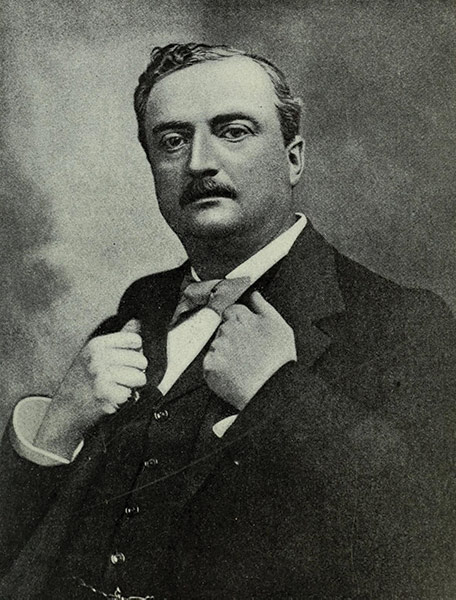

A member of a Catholic landed family from County Wexford, Redmond was steeped in the ways of the House of Commons and during his career became one of its most distinguished members. His granduncle, after whom he was named, his father and his younger brother, Willie, all served as MPs for Wexford borough. John Redmond was first elected for New Ross in 1881 but from 1891 until his death served as MP for Waterford city. The affinity between the Redmonds and Waterford was sustained until 1952. Deeply loyal to CS Parnell, Redmond remained one of his few followers at the time of the Parnell split in 1890-1, which sundered the IPP. He also played a leading role in organising an elaborate funeral for Parnell. After almost a decade of recrimination, the decision of the anti-Parnellites to accept Redmond as chairman of a reunited party in January 1900 helped bind the wounds of the split. Adroit in debate, Redmond was regarded as one of the finest orators produced by the party. He proved a competent chairman and moderating influence but was not a political chief in the mould of a Parnell or de Valera. One of Redmond’s unheralded achievements was to maintain the unity of the party, despite its many factions and bitter personal feuds.

“The position of Ulster proved the Achilles heel of home rule. Though he decried partition as the mutilation of the country, in the opening months of 1914 Redmond was compelled to accept some form of exclusion as the price of peace.”

Of imposing appearance, Redmond had a courteous but reserved and senatorial public persona. His solitary nature and dislike of social occasions often made him appeared aloof from party colleagues and political followers. When not in London, Redmond was happiest in his Irish refuge – his remote Wicklow estate house at Aughavanagh, once Parnell’s hunting lodge, where he could indulge in fishing, shooting and walking. The IPP leader married Johanna Dalton whom he met in Sydney while on a fund-raising tour for the party in 1884. She died in 1889 leaving three young children. Later Redmond found contentment through a second marriage to Ada Beesley in 1899.

A commanding Liberal victory in the 1906 election allowed the government to steer clear of Irish home rule. Nonetheless, Redmond facilitated legislation to provide cottages for Irish labourers, the Irish Universities Bill and the 1909 Irish Land Act. However, he was opposed to women’s suffrage and suspicious of the financial burdens associated with the old age pension. The position of the IPP was changed utterly during the constitutional crisis of 1909 caused by the House of Lords’ veto of the Liberal government’s budget. Holding the balance of power following two general elections in 1910, Redmond skilfully extracted concessions from the government on introducing a home rule measure and curbing the veto of the House of Lords. This was pithily summed up in his party’s ultimatum: ‘No veto, no budget’. The veto had been the main constitutional barrier to Irish home rule. The Parliament Act of 1911 limited the veto to three years so that the Lords could delay but not defeat outright a bill passed by the House of Commons. In this way, it was expected that the Third Home Rule Bill, an underwhelming measure introduced in April 1912, would become law in 1914. The years 1910 to 1914 were the high point of Redmond’s career. He had shaped British politics to Irish needs, broken the power of the House of Lords and won the introduction of a measure of home rule.

Throughout his career Redmond had misjudged the depth of unionist opposition to home rule. During the third Home Rule Crisis they were willing to prevent the home rule by force if necessary. To a politician wedded to constitutional methods as well as the spirit and practice of conciliation this came as a shock to Redmond. The position of Ulster proved the Achilles heel of home rule. Though he decried partition as the mutilation of the country, in the opening months of 1914 Redmond was compelled to accept some form of exclusion as the price of peace. He was also compelled to follow the unionist example by wresting control of the Irish Volunteers in the summer of 1914. The outbreak of the First World had profound implications for Ireland and for Redmond. Home rule was placed on the Statute Book on 18 September 1914 but it was immediately suspended for the duration of the war and accompanied by an unspecified provision for the special treatment of Ulster. What should have been his greatest triumph proved the hollowest of victories.

Redmond’s policy of rapprochement with British and Irish unionism through common martial sacrifice was made explicit in a pivotal speech at Woodenbridge on 20 September 1914 in which he committed the Volunteers to serve “wherever the firing line extends in defence of right, and freedom and religion”. In retrospect, the speech is often seen as the beginning of the end for the IPP but at the time Redmond had little scope for manoeuvre believing that Irish nationalists would be at a disadvantage after the war when an Irish settlement was debated. He also believed there was a moral duty to participate in the war. A more pivotal event was Redmond’s decision, in line with traditional party policy, not to participate in the wartime coalition cabinet. This marginalised the IPP which had nothing to show for its efforts beyond an image as a recruiting sergeant. The war also increased tensions within the leadership cohort of the party. After the 1916 Rising, two final opportunities to salvage home rule in the summer of 1916 and through the Irish Convention of 1917 caused irreparable damage to Redmond’s standing and an open breach within the party. The death of his brother Willie, his closest political confidante, in the Battle of Messines was a crushing personal loss at a time when the party suffered a succession of humiliating by-election defeats at the hands of Sinn Féin. Death spared Redmond witnessing the annihilation of his party in the December 1918 general election.

That Redmond’s failures were great should not obscure his most significant legacies: an unwavering advocacy of constitutionalism and a self-sacrificing dedication to Irish independence.

Dr Daithí Ó Corráin is a lecturer in history in DCU’s School of History and Geography. Ó Corráin’s broad research interests are 19th and 20th century Irish political, cultural and ecclesiastical history. At present, he specialises in the history of the Irish Revolution, 1912-23 and the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Ó Corráin is completing the first authoritative history of the Irish Volunteers from its inception in November 1913 to its re-branding as the IRA in 1919. He is also co-editor of the Irish Revolution series published by Four Courts Press.

Dr Daithí Ó Corráin is a lecturer in history in DCU’s School of History and Geography. Ó Corráin’s broad research interests are 19th and 20th century Irish political, cultural and ecclesiastical history. At present, he specialises in the history of the Irish Revolution, 1912-23 and the aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Ó Corráin is completing the first authoritative history of the Irish Volunteers from its inception in November 1913 to its re-branding as the IRA in 1919. He is also co-editor of the Irish Revolution series published by Four Courts Press.