Psychological trauma as a contagion

The transmission of psychological trauma from clients to criminal justice services staff has the potential to produce traumatised organisations. Sharon Lambert from the School of Applied Psychology, UCC and Graham Gill-Emerson, from the HSE Adult Homeless Integrated Team, Cork write.

Those who work in the criminal justice services will be very aware that many if not most of the people who find themselves involved in crime come from very challenging life circumstances. The profiles of people who are incarcerated in Ireland show that most emerge from situations of marginalisation, poverty, mental health and addiction.

While this information is not new or indeed a surprise, what has changed in the last decade or so is our understanding of the link between early adversity and later life outcomes. The last decade has seen an explosion in research on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and these experiences are being recognised as our greatest public health issue.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences study was the first study conducted on a national scale to show the wide-ranging impact of childhood trauma on healthy development, later-life negative health related outcomes, and its long-term costs to society. These effects are referred to as complex trauma and are so enduring and wide-ranging, that the diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) does not account for the impairments associated with them.

Research is emerging and ongoing, but it is argued that epigenetic changes occur in the presence of consistent toxic stress. Advances in neuroscience have revealed that exposure to toxic stress or trauma in childhood impacts on the ways in which the developing brain hardwires, with very serious consequences for later life functioning.

The adult brain is not fully formed until up to the 25th year of life and undergoes many changes throughout childhood and adolescence. Experiences of a warm responsive caregiver and exposure to a range of educational experiences facilitate healthy brain development; however, exposure to toxic stress or developmental trauma can cause synaptic pruning or the death of neural connections at just the time when the brain should be forming and growing.

Individuals exposed to high levels of stress have highly responsive fight or flight systems. Arousal of the sympathetic nervous system has consequences for thinking and behaviour; individuals whose systems are set on flight or fight experience both their internal and external world as threatening and often act accordingly, we will witness this as acting out.

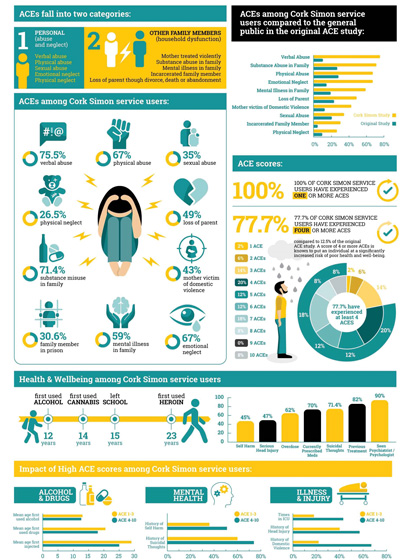

The original ACE study revealed that exposure to adverse childhood experiences (abuse, neglect and household dysfunction) is common with almost 40 per cent of the general population experiencing two ACEs. However, this decreases to 12.5 per cent for four or more ACEs. It has been argued that four ACEs are clinically significant and that each additional ACE has a dose response for increasingly the likelihood of illness and dysfunction (SAMSHA, 2018).

For example, a score of four increases the risk for attempted suicide by 23.2 times, seven times more likely to have alcohol issues and six times more likely to be raped within your lifetime. Also, over 50 per cent of people with four or more ACES report to having learning difficulties (WHO, 2014).

Secondary trauma stress differs to vicarious trauma in that it does not change a persons’ world view, it has instead been described as a syndrome among staff working with trauma survivors that mimics post-traumatic stress disorder.

The behavioural manifestation of this toxic stress can range from aggression to withdrawal. Often these behaviours are viewed as challenging when in fact the impacted individual has little control over these automatic systems. The ‘challenging’ behaviours presenting may well have once been required for survival in childhood and those very behaviours once required for survival are likely now to be the behaviours that led to the person come into contact with the criminal justice system.

For example, a very high percentage of people in prison are there due to drug or alcohol related offences. It is now argued by many that addiction is a response to unmet mental needs and/or exposure to developmental trauma. The use of drugs and alcohol by some initially helps them to manage their intense emotions and gives relief to trauma symptoms.

However, this substance use often becomes problematic leading to criminality such as violence and theft and consequently involvement with the criminal justice system. While many people know the link between early adversity and crime, the public often lacks empathy for those who commit crime, as too can professional.

A trauma informed environment is one that understands the impact of trauma on both service users and staff…

It is understandable that people get frustrated by another’s ‘bad behaviour’, however what the science now tells us that it is not just simply bad behaviour and bad choices. These behaviours are survival responses driven by a physiological system that is primed to respond to danger and that by not addressing the trauma and treating these behaviours as a criminal justice issue instead of a health issue, it inevitably leads to a cycle of more crime and trauma.

In order to make a meaningful change in reoffending rates we must look at the underlying trauma and develop systems that can respond to this. To not address the high levels of trauma in the criminal justice system leads to further traumatisation of those committing crime and those tasked with working them. It is increasingly recognised that working in systems where there are clients with high levels of trauma, impacts on those workers and this has been termed ‘a trauma contagion’.

Trauma contagion refers to the concept that working with trauma survivors may increase the risk for vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress and burnout for some. The terms are at times used interchangeably in the literature. According to Pearlman and MacIan (1995), vicarious trauma occurs following long-term exposure to the stories of traumatised service users and may cause decreased motivation and empathy.

An additional feature of this is a risk of a ‘distorted world view’. The experiences of workers in front line services represents a small minority of the general population as a whole, however, if a worker develops vicarious trauma they may perceive their world as more unsafe than the actual statistical risk. Staff may isolate themselves from others who do not work in front line services as they no longer hold similar views of risk, danger and trauma and may tend to gravitate more towards others who share similar occupational experiences.

Secondary trauma stress differs to vicarious trauma in that it does not change a persons’ world view, it has instead been described as a syndrome among staff working with trauma survivors that mimics post-traumatic stress disorder. This can be as a result of exposure to a service user’s trauma stories or it and can occur suddenly as a direct result of exposure to a stressful incident such as violence or finding a service user dead.

It must be noted that not all staff in front line services are impacted by secondary or vicarious trauma, and many report feeling satisfaction with their ability to offer care and develop a connection with service users.

Burnout occurs when the demands outweigh the resources and results in physical and emotional fatigue that may also result in disengagement from work and the depersonalisation of service users. This is an adaptive response where the stress becomes so overwhelming that in order to continue to function the worker needs to disengage from empathising with service users in order to protect one’s own mental health; this usually occurs over a period of time and may be an unconscious process for the worker.

Other symptoms of burnout may include feelings of helplessness and despair, insomnia, health risk behaviours (e.g. overeating, misuse of substances), difficulties within personal relationships etcetera. It can become systemic in that a whole organisation can be impacted.

Vicarious and secondary trauma have been described as ‘occupational hazards’ for those that work in front line services, therefore the organisations have a “practical and ethical responsibility to address this risk”. There are a number of ways that an organisation can respond to their staff needs; regular and effective supervision that is separate and distinct from line management, the focus is on the impact of the work. Reflective practice in supervision is an effective way to reduce the impact of the work on staff. A work environment that demonstrates good practice in relation to self-care is vital.

Addressing the trauma needs of both service users and staff results in a range of benefits for the organisation such as decreased critical incidents, increased morale and staff retention to name but a few. Many organisations that provide services to vulnerable and marginalised groups now recognise the importance of adopting a trauma informed work environment.

A trauma informed environment is one that understands the impact of trauma on both service users and staff and makes changes to policies, procedures and practices (SAMSHA, 2014). A trauma informed service does not necessarily treat trauma using clinical interventions, it does however recognise the levels of trauma within its organisation and responds to these.

Workspaces have become increasingly focused on output, risk management and paperwork. A focus removed from the people, both staff and service users, increases the risk for all involved, including the organisation itself. Workplaces need to invest in understanding trauma and its impact in order to maximise the safety of all within that organisation.