The Soviets of 1919

As Ireland embarks on the second half of its decade of centenaries focused on the First Dáil and the Irish War of Independence, eolas looks back at one of the more radical aspects of the revolutionary period: the workers’ soviets that appeared sporadically across the country in 1919.

1919 was a potent time for revolution and workers’ collectives in Europe; the successful Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917 had kicked off waves of social unrest aimed at establishing communism in Europe. A Bavarian Soviet Republic was declared in Germany; the Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted 133 days in between reigns of the First Hungarian Republic and over one million industrial workers took part in Italy’s Biennio Rosso (Two Red Years), starting in 1919. It was against this backdrop that Peadar O’Donnell and the workers of what is now St. Davnet’s Hospital rose the red flag in Ireland.

Monaghan Lunatic Asylum Soviet

The mental health services present today at St. Davnet’s were a separate facility in 1919, known as the Monaghan Lunatic Asylum. The workers of the asylum were unionised by the recently founded Irish Asylum Workers’ Union (IAWU) and worked an average of 82.5 hours a week. Workers, including those who were married, were not permitted to go home between shifts. The asylum was managed by a local committee, appointed by the county council. These committees tended to be dominated by the clergy, farmers, shopkeepers and publicans.

In March 1918, 96 of the asylum workers went on strike, picketing for higher pay and union recognition. The committee agreed to a war bonus of four shillings and union recognition, but the workers were not fully satisfied and threatened to strike again in September of that year, demanding a 56-hour week, a full pay rise of £1 over the pre-war rate and the right to go home between shifts. When the committee rejected their demands and warned that those continuing to agitate would be dismissed, the workers invited Peadar O’Donnell, Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) organiser, future leader of a Derry flying column in the War of Independence and Ulster representative on the Anti-Treaty IRA’s Army Executive, to negotiate on their behalf.

After two meetings between the committee, O’Donnell and IAWU representatives in December 1918 and January 1919 yielded no progress, O’Donnell warned that strike action was coming. The Resident Medical Superintendent, Dr. Conlon, claimed that the workers had little cause for complaint: “They work 12 hours every day for seven days a week, but they get every 13th day off and every 4th Sunday from 10am.”

On 24 January, the workers voted for action and occupied the asylum, hoisting a red flag outside and barricading themselves inside, declaring Ireland’s first ever workers’ soviet. The 200 attendants that took part laid out their five demands:

- A 56-hour work week with time and a half pay for overtime;

- freedom for married attendants to go home after work;

- a comprehensive increase of £1 on pre-war rates for all workers;

- skilled workers to get the going rate for their craft; and

- the equal treatment of female staff.

The committee attempted to break the strike by offering male attendants a pay rise and by sending in armed police, but the soviet held firm and their demands were granted, with the soviet ending after 12 days and socialist newspaper Voice of Labour hailing a “complete victory”.

Limerick Soviet

The most famous of Ireland’s soviets, whose existence would not have been possible had it not been for the War of Independence, which was raging at the time. When the IRA killed one Royal Irish Constable and injured another trying to rescue Robert Byrne, the republican trade unionist who was under arrest as he recovered from a hunger strike in hospital, the British Army declared Limerick city a Special Military Area, meaning permits were required to enter and leave the city. Byrne was wounded in the attempt and would die from his injuries. In response, the city’s United Trades and Labour Council declared a general strike on 13 April and the strike committee declared a soviet the next day.

British troops were boycotted, alternative currency was printed, food prices were controlled, and newspapers were published by the soviet. The historian Liam Cahill writes that the attitude to private property under the soviet was “pragmatic”: “So long as shopkeepers were willing to act under the soviet dictates [i.e. accepting the currency], there was no practical reason to commandeer their premises.”

The soviet became international news by coincidence, as sections of the international media were in Limerick to report on a transatlantic air race that was then cancelled. The soviet was ended on 27 April after Sinn Féin Mayor Phons O’Mara and the Catholic bishop Denis Hallinan called for its end. According to Cahill, it was The Irish Times who called the strike a soviet, warning that it was an attempt to emulate the Bolshevik Revolution.

Knocklong Soviet

May 1919 was a month of revolution in the small village of Knocklong in County Limerick. It was in the village’s now gone train station that Dan Breen, Seán Treacy, Séumas Robinson and members of the IRA’s East Limerick Brigade boarded a train to free Seán Hogan from RIC custody. In the same month, workers seized the creamery owned by the Cleeve family, Anglo-Canadian unionists who had heavily supported recruitment in Limerick during World War I, a war that made them around £1 million due to a food supply contract with the British Army.

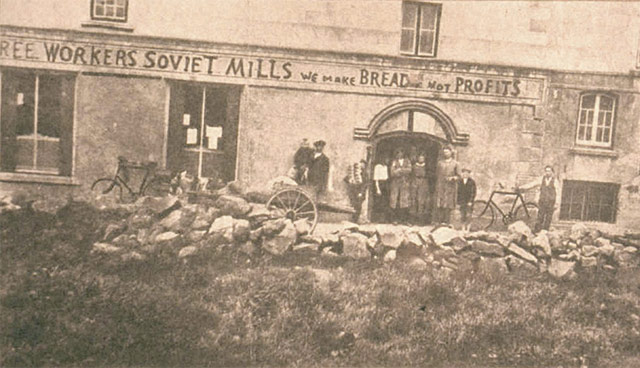

Employees of the Cleeves were some of the lowest paid in the country, with unskilled labourers earning an average of 17 shillings per week. A trade dispute led to the ITGWU seizing the means of production and running the creamery independently and erecting the red flag, along with a banner reading: “Knocklong Soviet Creamery: We Make Butter Not Profits”, which would be iconically emulated by the 1921 Bruree Soviet at a bakery and mills also owned by the Cleeves.

When the Soviet was ended after five days, the workers had won a 48-hour week, 14 days holidays, a pay rise and improved ventilation in working spaces. On 24 August, the Cleeves took out fire insurance on the creamery, which was burned down by the Black and Tans on 26 August.

Further soviets were established between 1920 and 1922 across various industries in Waterford, Cork, Tipperary, Drogheda, Roscommon, Rathmines and more. During the Civil War, the soviets drew the ire of both the Free State and the Anti-Treaty IRA, before fading away as the revolutionary period came to an end.