Household savings and a future economic recovery

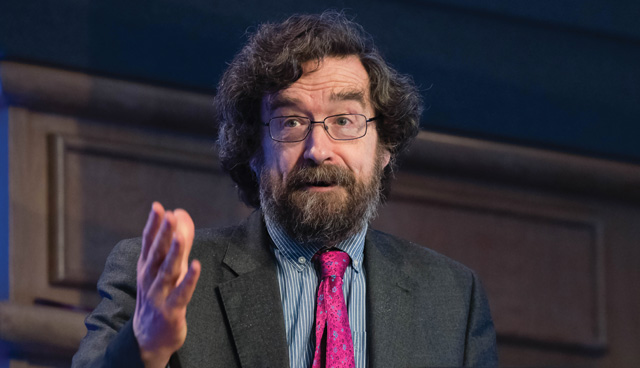

One feature of the Covid-19 crisis has been the exceptional level of government support for Irish households. Unlike the 2008-2012 financial crisis, households are likely to emerge with a stronger balance sheet. Professor John FitzGerald, a research affiliate at the ESRI, explores how household savings may impact economic recovery.

Governments across Europe have taken very extensive action to protect households from the consequences of putting their economies into cold storage. As a result, while some households will be worse off due to the massive rise in unemployment, their losses will be much less than they would be under normal unemployment regimes. Thus, across the EU, the reduction in aggregate household after tax income will be quite limited this year, in spite of the massive fall in output.

However, because of the lockdowns across the EU, which will continue for much of the year in some form, households cannot spend their income on the goods and services that they would normally do. While it is open to households to spend their money on the much narrower range of goods and services that are still available, this is not what is happening.

As a result, we have seen a massive reduction in spending on eating out, pubs, entertainment, accommodation, and tourism. There has also been a big fall in sales in a range of retail outlets, such as clothing. While the gradual easing of restrictions will see a pick-up in some areas of spending by the end of the year, there will still be a major reduction in consumers’ expenditure.

The combined effects of dramatic reduction in expenditure and a limited fall in incomes means that, at an aggregate level, households will be saving at an exceptional level this year. The EU Commission forecast a rise in household savings of 5 per cent of GDP this year in the Euro Zone. NIESR in the UK estimate a rise in such savings in the UK of 9 per cent of GDP. The Department of Finance estimate a rise in savings in Ireland in 2020 of 6 per cent of national income.

The Department of Finance also forecast that household savings will remain substantially higher than normal in 2021, leaving households with a pot of ‘excess’ savings at the end of the year amounting to around 10 per cent of national income or between €15 billion and €20 billion.

As with all forecasts, they should be taken with a grain of salt. However, the fact that this phenomenon of ‘excess’ household savings is affecting all of Europe (and also the US) suggests that it is, nonetheless, real. In the Irish and UK cases it is already showing up in an exceptional rise in household deposits in the banking system.

However, what is not clear is what consumers will do with their savings. There have been very few occasions in the past when households have had money but been unable to spend it. One of the few cases I can identify is the experience of Ireland during the Second World War. In that case nearly all imports stopped during the War, while exports of food to the UK continued. The result was that incomes rose, especially of farmers, but they saved much of their incomes when they found that the imported goods they normally bought were unavailable. However, after the War, there was a consumer boom in 1946 and 1947.

If households behaved as they did after the Second World War, and they spent all of this ‘excess’ savings in 2022, it would result in a consumer boom like we have never seen before. In spending the savings they would also generate a substantial tax windfall for the state, helping to put right the public finances, and provide a huge stimulus to the economy. Even if they only spend a fraction of it, it will still be a major factor in driving a recovery. The fact that similar spending by households might be taking place across Europe in 2022 could provide a great boost to an EU economy.