Electric vehicles: Learning from Norway’s lead

Norway’s fleet of electric vehicles (EVs) is the largest per capita in the world, with the market share of plug-in cars having reached 55.9 per cent in 2019. As Ireland looks to heavily invest in EVs, eolas analyses how Norway did it.

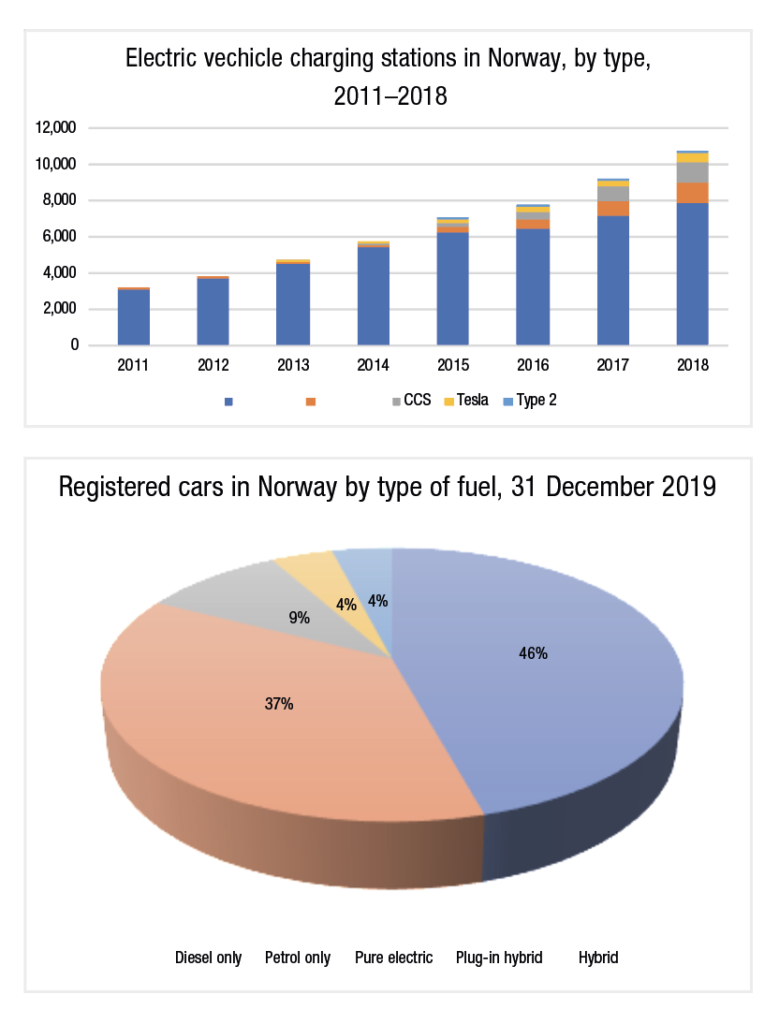

As of 31 March 2020, there were 390,367 light-duty plug-in EVs registered as in use in Norway. These consisted of 268,962 all-electric cars and vans and 121,405 plug-in hybrids. Since December 2019, Norway has had the largest European stock of light-duty plug-in vehicles, and the world’s third largest, behind only China and the United States. The country was the top selling plug-in market in Europe from 2016 to 2018.

Norway’s progress in addressing the balance of EVs to fossil-fuelled vehicles has not been halted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Pure EVs made up almost half of the country’s car sales in the first half of 2020, accounting for 48 per cent of all new car registrations from January to June, an increase on the 45 per cent recorded in the same period in 2019 and the 42 per cent recorded over the whole of 2019. The data from the Norwegian Road Federation showed the 48 per cent to be a record proportion despite a Covid-inspired fall of 24.3 per cent in overall car sales. The electric Audi e-tron was the most popular car in the country during the period.

EVs make up just 3 per cent of new cars worldwide according to the International Energy Agency, with Norway by far the largest market. Making the 48 per cent figure even more impressive is the fact that it accounts only for purely electric vehicles, while the worldwide 3 per cent also includes hybrid plug-ins. Despite this, perhaps as a sign of the ambition that exists within Norway when it comes to EVs, the Norwegian Electric Vehicle Association has criticised the level as insufficient if Norway plans on meeting its goal of all new cars sold being zero emissions by 2025.

The organisation has said that in order to be on track for this goal, sale levels should be over 50 per cent at this stage. Norway’s target is notably sooner than many European counterparts: Britain plan for the same to be done in 2035, France have same goal for 2040 and Ireland’s new Programme for Government has pledged to ban the registration of fossil-fuelled cars and light vehicles from 2030 onwards.

The Nissan Leaf hatchback battery EV was Norway’s best-selling new car model in 2019, which marked the first time in any country that a purely electric car topped the annual sales of passenger cars. 2018 analysis carried out by McKinsey and Company designated Norway as the only country in the world in the third stage of a disruptive trend with regard to EVs, meaning that the country had already reached a critical mass of EVs and that EV disruption in the country had become inevitable.

Norway’s fleet is also acclaimed as one of the cleanest in the world since roughly 98 per cent of the country’s electricity supply comes from renewable sources, predominantly hydropower. In 2017, Norway reached its 2020 target of average fleet CO2 emissions (85g/km) for new passenger cars three years early as a result of the country’s success with EV adoption.

How did they get there?

The road to Norway becoming a world leader in the adoption of EVs as a primary mode of public transport began in the 1990s, with the national government actively supporting a shift in car consumption since that time. Switching to EVs has long made sense especially in Norway, where hydropowered electricity means that a shift away from fossil-fuelled cars can have an even greener impact than it would in countries whose supply is still dependent on non-renewable sources.

The first government incentives for the purchase of EVs were introduced in 1990: an at-the-time temporary exemption from Norway’s high rates of vehicle purchase tax that became permanent six years later. Norway did not have the same relationship to cars as most countries in Europe did at that time, cars were still considered a luxury item and taxed highly. The scrapping of the vehicle purchase tax for EVs meant that their prices dropped to that of their fossil-fuelled counterparts.

In the following years, EV drivers were given the right to park for free in select municipal car parks, exempted from VST and road tax, allowed to take ferries without a ticket and allowed to drive in public transport lanes. Company electric cars are also taxed at a lower rate than fossil-fuelled company cars. With driving personal cars a highly taxed mode of transport in Norway, Oslo was and is still known for its expensive road tolls and parking changes. EVs were exempted from these in 1995 after A-ha singer Morten Harket (of “Take on Me” fame) and the leader of the environmental group Bellona refused to pay the tolls and parked illegally where possible in an electric Fiat Panda. The car was eventually impounded and auctioned to cover the costs, but the stunt had been successful in having the charges scrapped for EVs.

These incentives have changed over the years: those wishing to use public transport lanes must now be carrying at least one passenger and a 50 per cent rule was introduced in 2017, which allows local authorities to now charge EV drivers up to 50 per cent of regular parking fees, road tolls and ferry prices. Tax reductions were also introduced for plug-in hybrids in 2013, but it has been pure EVs that successive Norwegian governments have focused on.

Once the initial goal of 50,000 pure EVs had been reached in April 2015, the decision was made to extend incentives until 2017 to continue progress. Reforms such as the 50 per cent rule then began to appear after this.

Norway has also been noted for its extensive investment in EV charging infrastructure: in 2011, there were 3,123 charging ports in the country, all but 18 of them standard and publicly owned. By 2018, this number was 10,711, including 7,910 standard and publicly owned spots. For Ireland, or any other country trying to follow Norway’s lead, the lesson appears to be the old adage for a new age: if you build it and make it affordable, they — the drivers making change to EVs — will come.