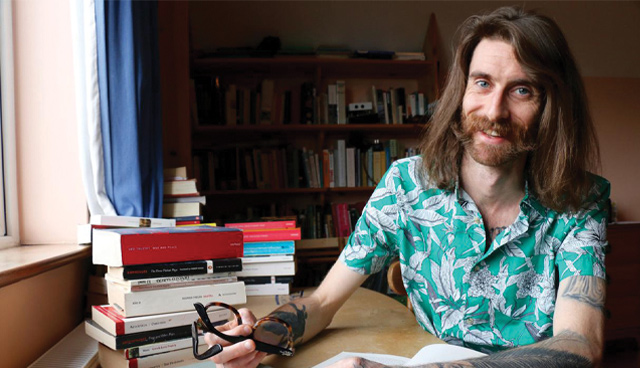

Tim MacGabhann: From Kilkenny to Mexico City

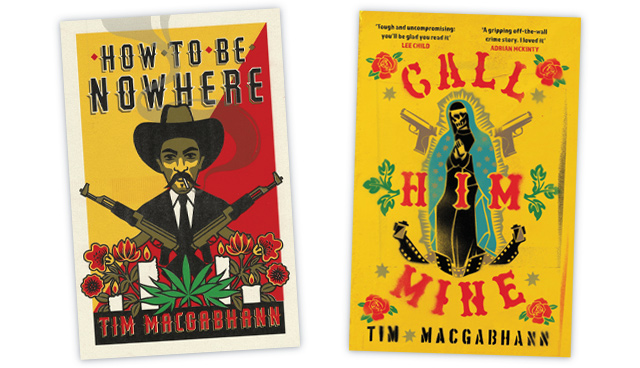

Having published his second novel in two years in July 2020, Kilkenny native Tim MacGabhann has a carved a niche for himself as a writer of well-crafted literary thrillers set in Latin America with both Call Him Mine and How to Be Nowhere. He speaks to Odrán Waldron about Mexico, the transition from journalism to fiction and the “pornographic” consumption of violence from his adopted homeland.

Now settled in Mexico City, having first moved there in the mid-2010s and returned to Europe for a year spent attaining an MA in the University of East Anglia, MacGabhann recalls what it was that had drawn him to the country in the first place. Having spoken previously about how an encyclopaedia in his grandparents’ house had imprinted the image of Mexican murals upon his young brain, MacGabhann traces the timeline between his first viewing of those pictures and the eventual, inevitable move.

“I had a really misspent adolescence; I studied quite hard and went to the gym a lot. I used to just sit down reading the paper after the gym before going back to study and any time there was anything in the news about Mexico, I would just hoover it up from the age of about 15,” he says. “The Calderón period, the ‘drug war’, kicked off when I was 17. I remember seeing photos of people my age navigating heavy army presences on their walk to school and that jarring feeling of an intensely militarised setting. The soldiers looked like the lads from [Paul Verhoeven’s 1997 futuristic satire of fascism] Starship Troopers, they looked like they were from the future. It looked like the future of war, the persecution of civilians in totally normal settings for somewhat accidental reasons. It was such a jarring thing to see this place, that I had idealised as a safe haven in my head, so threatened. It felt like a personal insult even though I had no skin in the game.”

MacGabhann was further immersed in the Mexican culture that was becoming a constant in his life as a child when visiting an aunt with Mexican family with his parents, who had lived in Los Angeles in the 1980s. Visiting Redondo Beach, Long Beach and Downtown Los Angeles, noted for its similarities to Mexico City’s Centro Histórico, he recalls his impressions: “I remember walking around with my cousins and aunts and uncles and felt really close and embraced, quite warm sitting there on the beach and seeing Chicano culture unrolling across the sand. It felt like a version of Ireland somehow; the family stuff was a bit happier looking, without that John McGahern twistedness that we have at home. It felt a bit freer, like an alternative. It was so interesting to see things that were so different from your own culture but filled with similarities.”

What I wanted to do as a journalist was inhabit another life and get it across to the reader and I’ve realised that I can just do that with my fiction. I have synthesised my experience of journalism and my belief of the importance of what fiction can do.

The young MacGabhann who idealised Mexico grew up and moved on to Trinity College Dublin, where he studied English and French literature and took to “hiding in the library”. It was in his refuge, toward the end of his third year in university, that MacGabhann began to embrace the literature of Latin America. “I went to the big names first: Gabriela Mistral, Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges and then Roberto Bolaño was basically unavoidable,” he says. “The way he was being spoken about, it sounded like a synthesis of all my concerns. This was around 2010, 20 years on from the events he was writing about in 2666, so I was matching up 2666 with the newspaper articles I was reading and thinking that this whole thing was spinning on an independent axis and the fabric needs constant updating by the people paying attention to it. I felt really drawn to it.”

From these writers and others, MacGabhann gleaned how it was that he felt he should write about Mexico, his adopted home. “There’s an awful lot of crap about bearing witness and messianic white saviour nonsense that goes with that; I didn’t ever want to do that,” he explains. “I wanted to live here rather than hover over it. I wanted to be as close to what people were living as possible. When I turned up it felt like home immediately, probably because I had been constructing it as an alternative home in my head for some time. It drives me crazy because home drives anyone crazy, but I’ve been here for so long at this point, whenever I leave, I feel weird.”

Call Him Mine and How to Be Nowhere are both unmitigated successes in this regard, offering the reader a razor-sharp detail that is never judgmental when describing the narrator Andrew’s surroundings. The two are the first parts of a series, which follows Andrew, an Irish journalist in Mexico City, as he investigates the death of his partner Carlos and the collusion between the Mexican state, cartels and oil companies. Its action across the two novels takes the reader through various parts of Mexico, Uruguay, El Salvador and Guatemala. When it is put to MacGabhann that he has been so successful in living in Mexico rather than hovering above it, to the point where his writing now mimics Mexican patterns of speech in English — “Probably I wanted to scratch the back of my head or something,” is an example of Andrew’s speech put to him that sounds more Mexican than Irish structure-wise — he laughs. This is not to say that Andrew, the by-turns terrified and intrepid reporter who constantly harks back to his grandparents’ house in Bagenalstown, is an Irish man speaking in Spanglish; his is the talk of an immersed immigrant, littered with the ahs and wells of Irish speech too.

“I’m barely conscious of it anymore,” he says. “Where I have ran into trouble with reviewers has been to do with that, I think, because it looks like an affectation but I’ve no idea that I’m doing it. People talk about local colour in the description or the setting when the people aren’t American or European, but for me it’s just what I see.

“Beckett says it as well, that all of his books have an insomniac, ashen quality. He wrote at night when he couldn’t sleep so his sensory input was reflected in the linguistic output. My partner makes a lot of jokes about my Spanish, wondering where I picked things up. I read a lot of Spanish too and have always been so drawn to the aesthetic of Latin American literature as distinct from European Spanish literature and I think that whatever you’re attracted to you can’t help but be sucked in. I’ve also got these really weird rules about sentences; I try not to begin sentences with the first-person pronoun too often because it sounds like someone boring your arse off in a pub. If you impose these rules on yourself, you end up speaking in a weird way and then the rest of the artifice is filled in by my environment, I think.”

That environment is so vividly realised not only because of MacGabhann’s immersion, but also perhaps due to his history as a journalist in Mexico and further afield in Latin America. Having originally taught English in Mexico City, MacGabhann contacted the journalist Alfredo Cortado to organise an interview for a freelance job. Cortado instead invited him to a foreign correspondents’ pub night, and from there MacGabhann became a freelance foreign correspondent, covering the realities of everyday life for the millions of people affected by Mexico’s well-documented violence and poverty.

I would watch Sicario or any of these horrible action films and just think to myself that these people don’t know what they’re doing. They want to show these beautiful arcs of blood spray or Homeric tumbles; first off, it doesn’t happen like that and second, you’re leaving out the biography. So, my question is: do you want ultraviolence, the actual truth of violence in your face or do you want this pornographised distortion?

“The fiction dream was always there; it was definitely the first one. I had a really rough experience at the end of university trying to get a first novel, which is now compost, published. I gave up on wanting to be a fiction writer from about the age of 22 to 27 or 28,” MacGabhann says. “All I had wanted to do was write, I wasn’t really good at anything else and so I started doing journalism. I had a lucky break because it’s quite a close-knit community here.

“I started going to that pub night every week, chatting and picking up jobs. It was scratching the writing itch and the desire to be socially engaged. As a freelancer, I could pitch whatever I wanted so I would go to the places that I wanted to visit like Veracruz. My friend John and I were doing this story that felt very big to us, but we were having trouble placing it. Our editor then got pulled away to cover Trump so that was the end of that, John ended up getting a different job. I was left with a big chunk of reportage done, an itch to go back to fiction and the sense that I had reached the end of the road with journalism. It wasn’t that there was nowhere for me to go but I knew that I could stay churning and burning of dailies or going into the magazines, but they all seemed to be sinking.”

MacGabhann took his reportage, fictionalised it and produced a novella that got him admitted to the University of East Anglia’s prestigious Creative Writing MA. From there, Call Him Mine was born and from that came How to Be Nowhere. Both have been published by Weidenfeld & Nicholson and have been the subject of rave reviews and impressive sales. More importantly, MacGabhann sees in these books the writing he had always wanted to do.

“Coming on four years into it, I don’t know if I want to do the journalism again,” he explains. “What I wanted to do as a journalist was inhabit another life and get it across to the reader and I’ve realised that I can just do that with my fiction. I have synthesised my experience of journalism and my belief of the importance of what fiction can do. I’ve got the time and financial space because of the last few years of momentum to really explore that. I’m now exploring the kind of journalism I always wanted to do, except I’m doing it from my desk, not too far away from the donut shop.”

Part of what MacGabhann had wanted to do with that writing was turning up the violence in How to Be Nowhere, where Andrew finds himself increasingly numb to and, eventually, participating in the violence that had previously surrounded him in Call Him Mine. This, he says, was a conscious decision intended to confront the reader with the ultraviolence that has become associated with Latin America through TV shows such as Narcos and films such as Sicario and ask them if it was truly what they wanted. Deaths are manifold in How to Be Nowhere and are never of the heroic kind shown on television. One of the most memorable recounts Carlos, a violent but jovial cartel hitman fading away in a car seat as his bullet holes weep blood. Scenes like this, and the overall cathartic, blood-soaked tone of the second novel were responses to what MacGabhann sees as the pornographic consumption of Latin American violence by western audiences.

“I think there’s a real pornographic element attached to it,” he explains. “If you walk to any newsstand, you will be presented with a wall of front pages of people who have been flattened by buses or murdered in some horrible way, with a joking pun headline on the tabloids. You’re unwrapping your Kit Kat and there’s a head staring back at you. One of the last normal things I did [pre-Covid-19] was go to a protest, a women’s march, that had been set in motion by a really graphic femicide, probably the most horrible image I’ve ever seen, even in horror films. This was the flint to spark this protest to say that enough was enough of this pornographic consumption, there were about 60,000 people at this thing inspired by this horrible image. These are the best-selling papers in the country, so maybe my opinion of what people want is kind of skewed by that.”

In this stylised ultraviolence was also a conscious attempt at reclaiming the narrative of this violence, a centring of the victims and an acknowledgment of the lives destroyed. “I’ve been to a lot of murder scenes and seen a lot of bodies and I know that every face and every head and every smell has a family history and a life behind it,” MacGabhann explains. “I’ve looked around people’s houses and seen their favourite boxsets and have gone from those to their blood on the floor. That filled me with such huge sadness, this infinite interior life as complex, granular and textured as mine or yours just spilled into the carpet. I would watch Sicario or any of these horrible action films and just think to myself that these people don’t know what they’re doing. They want to show these beautiful arcs of blood spray or Homeric tumbles; first off, it doesn’t happen like that and second, you’re leaving out the biography. So, my question is: do you want ultraviolence, the actual truth of violence in your face or do you want this pornographised distortion?”

Concluding, MacGabhann reflects on how his time living in and writing about Mexico has helped him to understand Ireland and himself better: “The shapes of Irish history didn’t really recede into their clear form for me, analytically, until I moved here. I didn’t really understand the different ways that colonisation can operate. In a new environment, you always draw parallels with what you know, you have to account for differences because otherwise you’ll do some terrible, patronising equation between disparate experiences. When I was beginning to understand my two homes, I was holding them up to a mirror and beginning to realise that the larger currents of history are shared. I had people explaining Mexican history to me through parallels that I had failed to understand.

“When it comes to writing most clearly about myself, autobiographically, I’m only able to do it if I change the major particulars completely. I have a few autobiographical short stories that will be popping up that don’t look autobiographical because they’re about a guy called Diego, but they’re the most personal things I’ve ever written. By taking a mirror image of myself that is different in so many ways with major differences, that forces me into finding these tiny little bits of connective tissue to have him tightly knitted to me. The more tightly knitted he is, the more tightly knitted the reader will be. I never felt like I was pushing back against the paternalistic crap that Americans push about Mexico because as a reporter, a neighbour, a friend, you just want to be as close to and genuine with the people you’re around. You are aware of difference, but you don’t attribute any value to it.”