Unaffordable: The cost of partition

A united Ireland could cost as little as one per cent of the Republic’s annual economic output, a new policy paper by Sinn Féin suggests.

While there are many facets to the discourse on Irish unity, one consistent theme is that of the cost. Those opposed to or indeed indifferent to reunification tend to look at the cost that would be incurred, with many fixated on one figure: £10 billion, one rough estimate of the annual subvention required by the North’s economy from the UK Exchequer. United Irelanders focus instead on the potential benefits of an all-island economic approach, which they contend would outweigh any cost.

Consensus on the subvention cost does not exist and its absence remains a stumbling block for those looking to enhance the discussion on the economic benefits reunification could bring across the island of Ireland.

As the economic impact of Covid-19, coupled with economic detriments of Brexit transpire, the conversation on the viability of a reunification has intensified. Recognising this, Sinn Féin’s November 2020 policy paper, Economic Benefits of a United Ireland, claims to challenge the “existing narrative” that the State cannot afford the North and that a united Ireland is not economically viable.

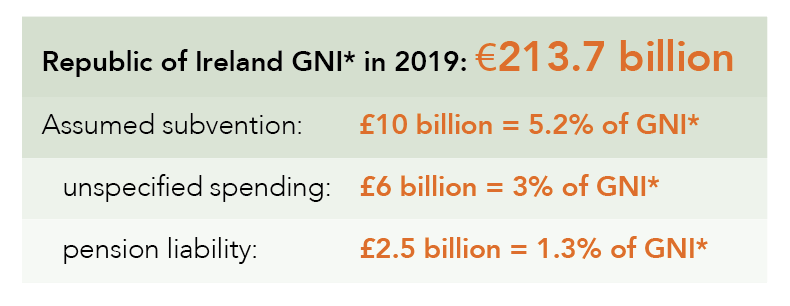

Analysis of the subvention required by the North, or the spending gap currently plugged by the British Government that would hypothetically need to be absorbed by the Irish Government, produces an interesting alternative figure. In 2018-19, expenditure in the North, incorporating spending on services and of accounting adjustments, was £27.888 billion. Revenue raised totalled £18.5 billion. This leaves a deficit, therefore, of between £9 billion and £10 billion.

However, Sinn Féin argues that this figure is an inaccurate reflection of the true cost and does not distinguish between spending on services within Northern Ireland (identifiable spending) and those British spending priorities for which costs are passed to Northern Ireland (non-identifiable spending) such as funding defence, paying down national debt or overseas commitments. Removing non-identifiable spending (£2.1 billion in 2018-19) would reduce the subvention figure to £6 billion.

Again, this could be reduced further when it is considered that £3.5 billion is spent on pensions, an expenditure that should not have to be incurred by the Irish State because pension rights have already been accrued under national insurance contributions. “The ultimate subvention figure will be determined by the outcome of negotiations. This figure will range from between £2.5 billion to £6 billion,” the document states.

For context, the analysis highlights that this figure equates to between just 1.3 per cent and 3 per cent of output of the Irish economy in 2019 (€213.7 billion GNI* in 2019).

Sinn Féin argues that cost alone should not be the only determining factor when considering reunification and emphasises the potential economic benefit of an all-island approach. Partition, the party states, has left the North with the slowest growing economy on these islands. For instance, around 20 per cent of its workers earn less than a basic living wage.

“It is recognised that having decisions taken in Westminster has been to the economic detriment of the North… The OECD categorised the North as essentially ‘peripheral with respect to its political influence’ on Westminster for innovation-related policies,” the document states, pointing to the benefit of an united Ireland allowing for the development of a “bespoke localised macroeconomic strategy”.

The border

The region which stands to significantly benefit most from reunification are the border counties, according to the analysis, which asserts: “Since partition the border corridor has effectively been consigned to periphery status limiting the economic potential of a significant section of our island and therefore of the whole island economy.”

Productivity in the southern part of the border region is stunted at 54 per cent of the island average and just 61 per cent of high-income European economies. “It is a region that should be heavily integrated and coordinated for its largest economic sectors… However, it is divided by two different currencies and two states competing for investment and economic activity,” the report says.

“Partition has trapped the border region in a vicious cycle… Reunification would allow for more coordinated and strategic economic development across the island and especially within the border region, attracting more investment, improved productivity, and with it enhanced essential infrastructure.”

The EU

Underpinning its analysis of the economic detriments of Brexit, Sinn Féin emphasises the EU’s assurance in April 2017 that in the event of reunification, the North would automatically re-enter the European Union.

Highlighting economic projections of severe long-term reductions in the output of the Irish economy in the decade after a hard Brexit of between 2.3 and 7 per cent, the party adds that analysis of the current trading relationships between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, in all circumstances, will be impacted by increased non-tariff barriers and increased administration burdens.

The analysis recognises the Irish protocol’s role in mitigating the threat of severe disruption on cross-border trade, important when considering that some £4.2 billion was exported by businesses in the North to the Republic.

Acknowledging that the impact on trade between the North and Great Britain remains unclear, the discussion paper seeks to dispel the assertion that Britain is the North’s most valuable trading partner, arguing that this is based solely on the value of trade being higher. This, Sinn Féin suggests, overlooks the fact that more business trade flows from the North to the Republic rather than from the North to Great Britain. It also fails to consider the role of north/south supply chains and intermediary trades prior to any sale from the North to Great Britain.

“The assertion that trading between the North and Britain would be negatively impacted or that the North has more to lose in terms of trading with Britain in the context of Irish unity is debateable and can be rebutted in numerous ways,” it states. The paper emphasises the threats of Brexit, including customs costs and barriers on the North’s exports to Great Britain and evidence that, even in advance of tariffs, northern businesses are becoming less reliant on trade with Great Britain (NISRA figures show a 9.3 per cent decrease in 2018).

Evidence of this, it suggests, is that in 2018, for the first time since records began, the North exported more goods to other countries (£11.2 billion) than to Britain (£10.6 billion).

Summarising, it states: “Reversing the negative effects of Brexit is an economic necessity. Irish unity would allow the North to enjoy full benefits of EU membership including access to the European market and to substantial funding, and the investment opportunities offered through EU programmes and institutions, while enabling further all-Ireland integration.”

Energy

One area in which the discussion document is less authoritative is on the potential of “the green economy”. In the absence of concrete figures on potential economic benefits, it opts instead to explore Ireland’s underperformance in developing a green economy to date and points to “untapped avenues”.

Noticeably, it omits reference to Ireland’s Single Electricity Market (SEM) as an example of where all-island integrated energy policy has proven to be beneficial and could serve as a template for wider green initiatives. However, the document does recognise the unique challenges facing the North’s climate action objectives in the absence of fiscal levers.

“Irish unity is the route through which economic benefits of the necessary transition including green jobs and greater security of energy supply can best be realised. The benefits from economies of scale and all-island spatial planning apply equally to the green economy,” Sinn Féin states.

“Partition means that the benefits of a transition to a zero-carbon economy will be dampened significantly, as both parts of the island compete against each other for private renewables investment while operating two incoherent and potentially conflicting green economic agendas.”

In concluding, Sinn Féin says that the document is intended to advance the economic case that the entire island of Ireland will benefit economically from unity. “It is not a question about whether we can afford Irish unity, the fact is that we cannot afford partition.”