Climate change and Irish water resources

Conor Murphy, professor of geography at Maynooth University, speaks to eolas about how climate change will affect Ireland’s water resources and how having access to longer drought records now means that we have a better understanding of projections of future drought.

“Until recently, drought was somewhat a forgotten hazard in Ireland, but we had the 2018 drought and the spring of 2020 drought as well,” Murphy, who also sits on the National Climate Change Adaptation Committee and has acted as expert reviewer for reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, begins. “Looking at how drought may change or manifest in the future is an important question.”

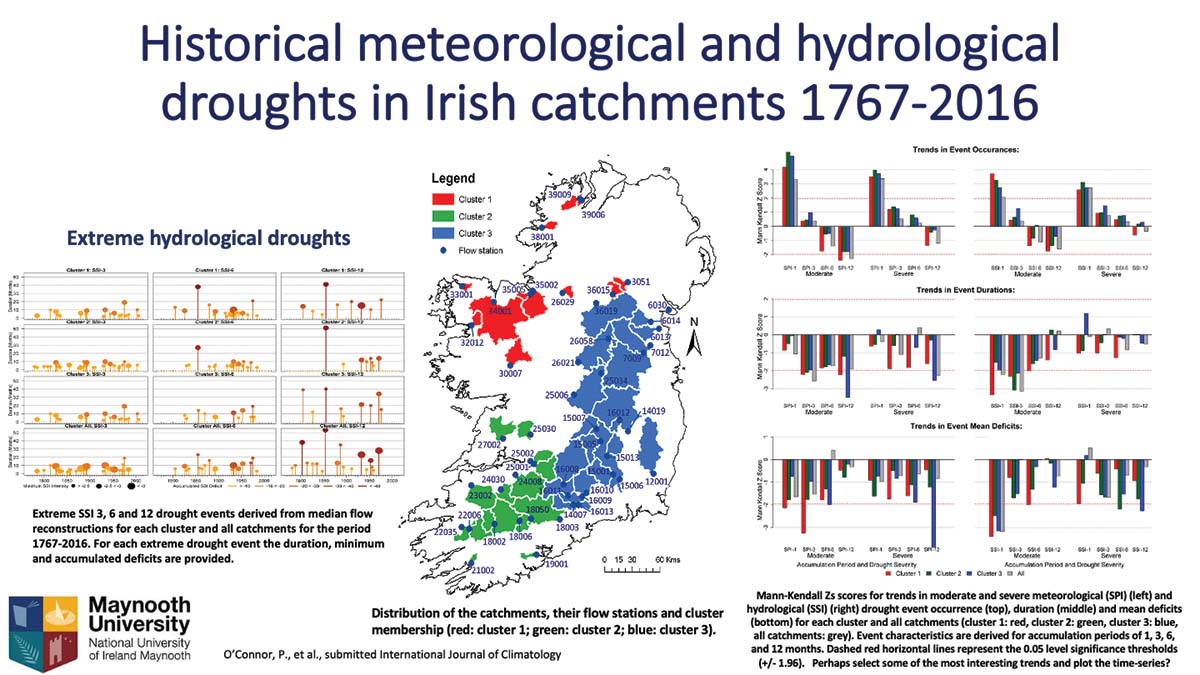

Discerning changes in hydroclimate variables is a major challenge, Murphy says. In Ireland, there are typically very short-lived records, with the monitoring of river flows across the country starting mostly in the mid-1970s. Murphy’s work has been focused on exactly that task over the last number of years, leading him to rescue the large amounts of data that are held on paper records in Met Éireann’s archives. “They have given us valuable insight into the range of extreme events we have experienced in the past and our ability to track and document ongoing changes,” he says.

The second challenge is that hydrological factors can be subject to confounding factors such as land use change, agriculture, urbanisation, extraction, and discharges. These can all confound and make complex the ability to detect changes in a catchment. In order to deal with this issue, Murphy and his colleagues have been working on identifying a reference hydrological network where those hydrological factors are minimised. Again, this involves the plumbing of the longest records in an effort to extend them back in time.

“Our work has resulted in Ireland having one of the longest continuous rainfall records anywhere on the planet,” Murphy says. “We have been able to develop a multi-century rainfall series from 1711 to the present. It reveals to us several things. Firstly, the extent of the variability and change that is evident over these long-term records. We can see, for example, that the driest summer in our records is the summer of 1800. A lot of the very dry extremes happened very early on in our records. Decadal rainfall, from 1711 to the present, shows a clear trend of wetter weather over the last 300 years, whereby the last 10 years has been the wettest decade in the entire series. There are some issues with going back to the 1700s and 1800s; for example, we suspect that the early winter periods are too dry.”

Murphy and colleagues have also been using rainfall records from across the island, from 1850 until present, inputting them into European scale analysis to examine variability, change and trends, for example in summer drought, looking at accumulated deficits over the summer months of June, July and August. “What we see across Europe is a mixed bag in terms of the direction of trend, but it is worth highlighting significant trends in Ireland towards more severe summer drought events,” he says. “What you can see across the European scale is that trends are often largest and most significant in Ireland’s east, indeed even in different time periods.”

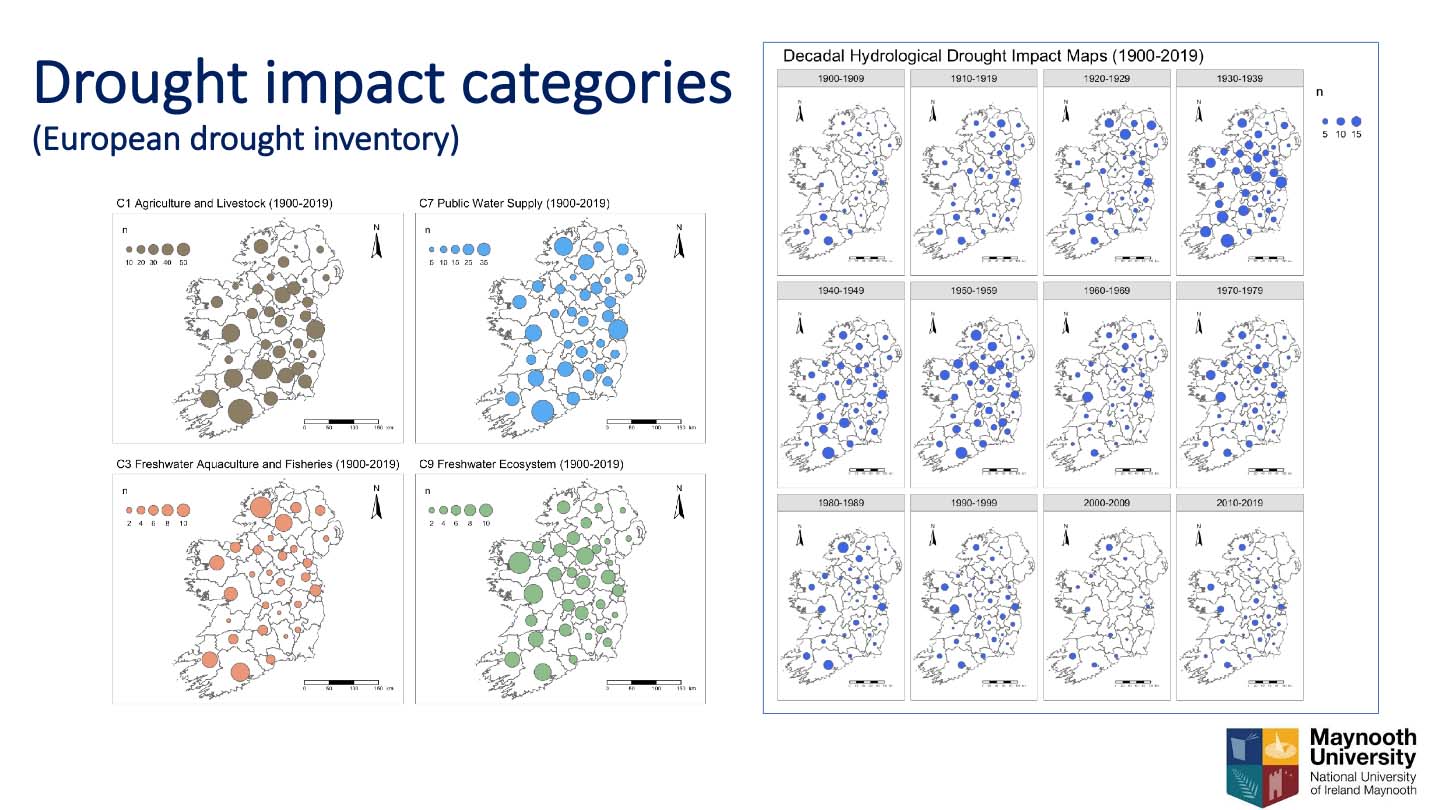

Murphy continues: “An important question to ask is how this links with impacts. It is not always the case that when a drought event occurs, it results in socioeconomic impact, and we have a huge amount of data available to us. Over the last number of years, we have been systematically going through newspaper records all the way back to the 1730s, with a focus on the period from 1900 onwards. Again, we see a very clear picture, similar to what the observations are showing us; that recent decades have seen a paucity of water or hydrological impacts relatives to the previous decades. Look at decades before the 1950s, for example, particularly the 1930s and the extent of drought across the country.

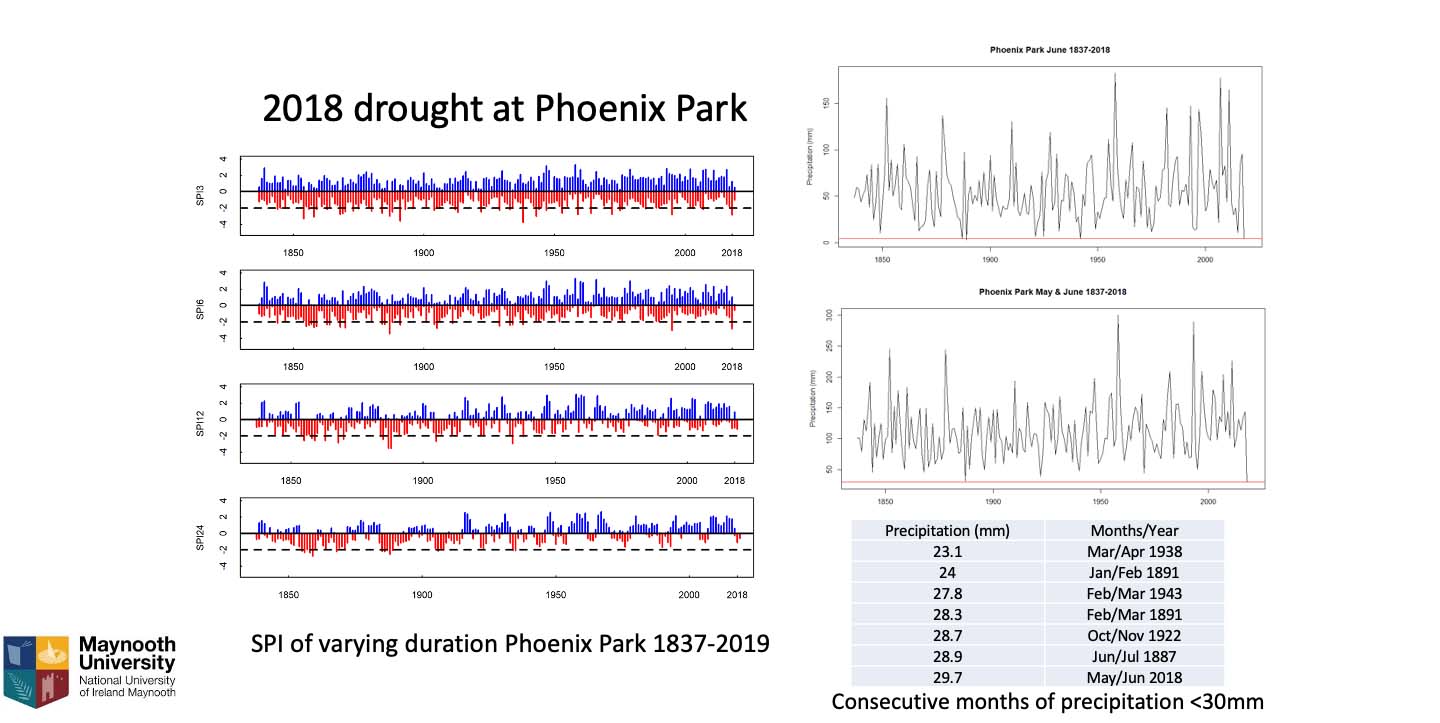

“The 2018 drought in the recent context is an extreme event, but when we get into longer historical periods, it is not an extreme event and there are far more severe droughts. The key thing that our records tell us is that 2018, for shorter duration periods, was an extreme event but there are more severe events in terms of the duration of accumulated losses possible in Ireland. This speaks to other work that we have undertaken, looking at the possibility of persistent dry runs in Ireland. Compared to England, Scotland and Wales, Ireland has a persistent likelihood of long dry runs which are important to take account of in the context of drought planning.

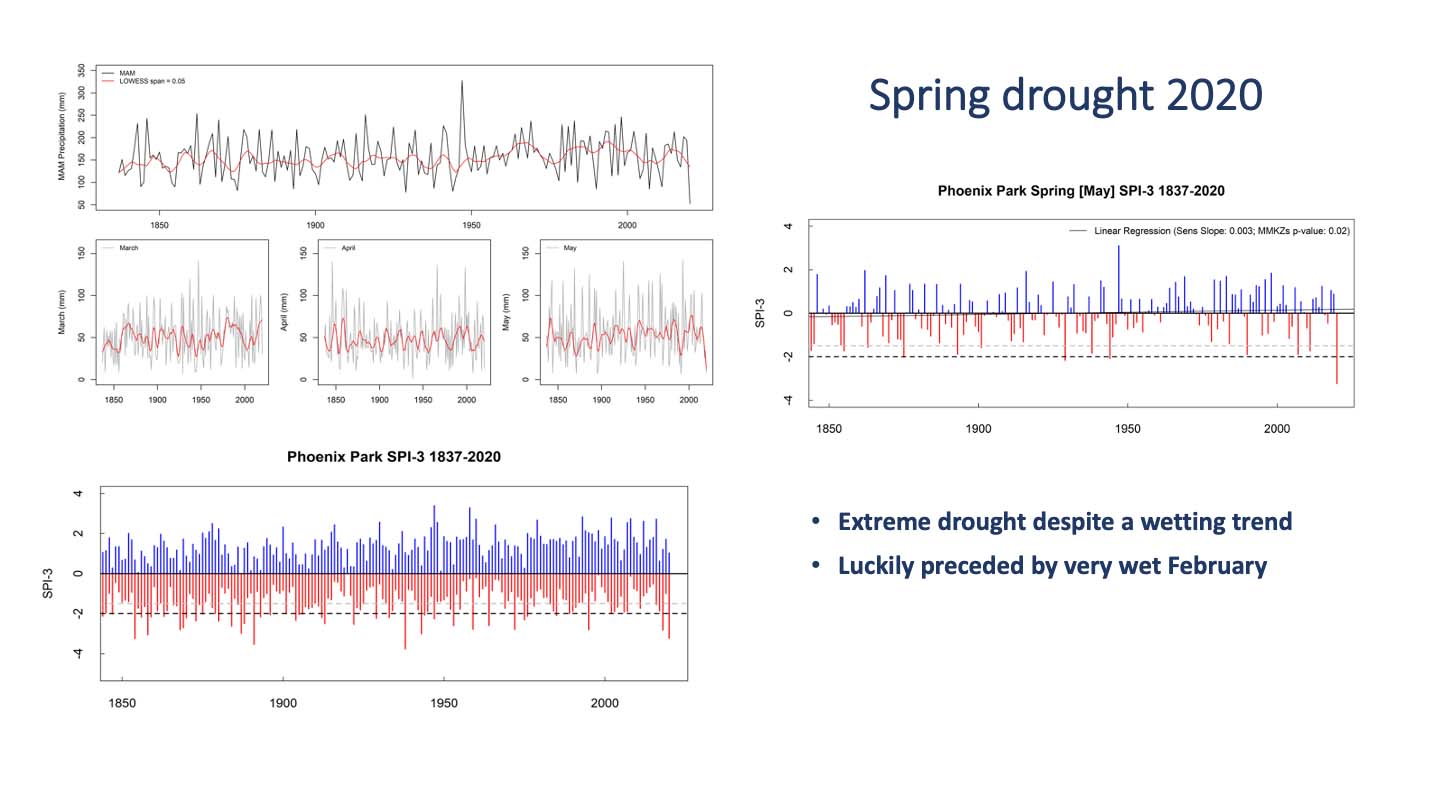

“The spring drought of 2020 was remarkable in terms of the deficits. Again, looking at the three-month accumulation period, we can see that it was an extreme event but there are other extremes that surpass it. It is interesting to note that in spring we see a trend towards less severe droughts, despite this 2020 did occur. Luckily for us, despite the context of last year, it was preceded by a very wet February.”

When attempting to address the question of the changes projected for hydroclimate variables for the coming century, there are modelling chains to hypothesise what kind of society may be realised, how greenhouse gas emissions may change in the future, and the concentration of atmospheric change to use a climate model that is then run through impact models to give us a sense of local impacts in order to give us an idea of local impact models.

“What we see in our research using the most up-to-date climate models are different levels of impact from the sustainable future scenario to a more fossil fuel heavy one. In terms of drought, it is the summer that is most important, and we are seeing a range of significant reductions in summer river flows for the catchments we have assessed so far,” Murphy explains. “With more emissions in the future, these decreases would become more severe. When we trace that through to future drought magnitude and frequency, looking at it seasonally, fundamentally what we see is a decrease in both magnitude and frequency in winter and an increase in magnitude and frequency in summer.”

“We need to not just think about climate change, it does not happen in a vacuum, we also need to think about the other pressures on water resources in terms of population growth changes and demand.”

Concluding, Murphy stresses the need for the kind of information his work has captured in order to understand how our water supply might change: “Fundamentally, good decisions around resilience depend on the types, diversity and quality of information used to inform adaptation. I think it is really important that we go beyond just using climate models to integrate those historical records, to stress test our water management plans and adaptation actions. If we do not, we risk building fragility into our decisions.

“We need to not just think about climate change, it does not happen in a vacuum, we also need to think about the other pressures on water resources in terms of population growth changes and demand. Once we understand existing vulnerabilities, we can identify actions that might deal with them. They need to be assessed in terms of their social acceptability, economic appraisal, regulatory context, and technical feasibility. Out of that kind of context, we come up with an acceptable set of measures, which should be focused on reducing future vulnerability, again taking account not just of climate change, but of non-climatic pressures. It is critically important to test those preferred measures in terms of their robustness to future change, doing sensitivity analysis to evaluate how successful they may be and looking at integrating adaptation principles in terms of least cost actions, robust activities that make sense now no matter what the future is etcetera, setting out pathways in terms of when risks emerge and when actions should be initiated.”

Conor Murphy

Conor Murphy is a professor in the Department of Geography and the ICARUS climate research centre at Maynooth University. He has worked extensively in recent years on developing our understanding of historical droughts in Ireland, together with the assessment of climate change impacts on hydrology and water resources and how best to integrate climate information into decision making. He has published over 60 papers in leading international journals including Nature, Science and Nature Climate Change and his research is currently funded by Science Foundation Ireland, the Irish Research Council, the EPA and Wellcome Trust.