European Chips Act forthcoming

The European Commission is preparing to put forward a European Chips Act aimed at vastly increasing the EU’s manufacturing of semiconductors and weaning the continent off of its digital reliance on China and the US.

The European Chips Act, if passed, would plan for the EU to account for at least one-fifth of the world market value of cutting-edge and sustainable semiconductors by 2030. The Act would make up just part of a number of initiatives in the so-called Digital Decade for the EU in which the Union is looking to strengthen its hand in the digital market, with funds from a centrally managed programme to boost research, deployment and the manufacturing of these microprocessors being matched by an ambition to have built the EU’s first quantum computer by 2025.

“We need to link together world class research, design and testing capacities,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said in her State of the Union address. “The aim is to jointly create a state-of-the-art European chip ecosystem, including production, that ensures our security of supply and will develop new markets for ground-breaking European tech.”

The Commission had in the past created an industrial alliance on microprocessor and semiconductors in an attempt to support companies manufacturing the next generation of microchips and to return offshored manufacturing to Europe. Microprocessors are now ubiquitous in the digital world, to be found in smartphones and watches, cars, trains and smart factories, and Europe’s plans to increase its manufacturing of the technology are central to its plans to expand digitally and lessen reliance on Asia in particular. Indeed, von der Leyen commented that Europe’s digital plans would be impossible without these chips.

As von der Leyen noted in her speech, Europe’s share in the semiconductor market has shrunk; microchips made in Europe currently account for 9 per cent of the European microchip market today, a steep fall from the 40 per cent rate 30 years ago. 90 per cent of the EU’s data is managed by US companies, many of whom have European headquarters in Ireland, and under 4 per cent of the top performing online platforms are European. Semiconductor sales by European companies totalled €3.2 billion in May 2021, a 31.2 per cent increase on the sales level of May 2020, but the Commission estimates that the EU

would have to multiply its annual sales of microprocessors by five in order to reach a 20 per cent share of the world market by 2030.

“The aim is to jointly create a state-of-the-art European chip ecosystem, including production, that ensures our security of supply and will develop new markets for ground-breaking European tech.”

— European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

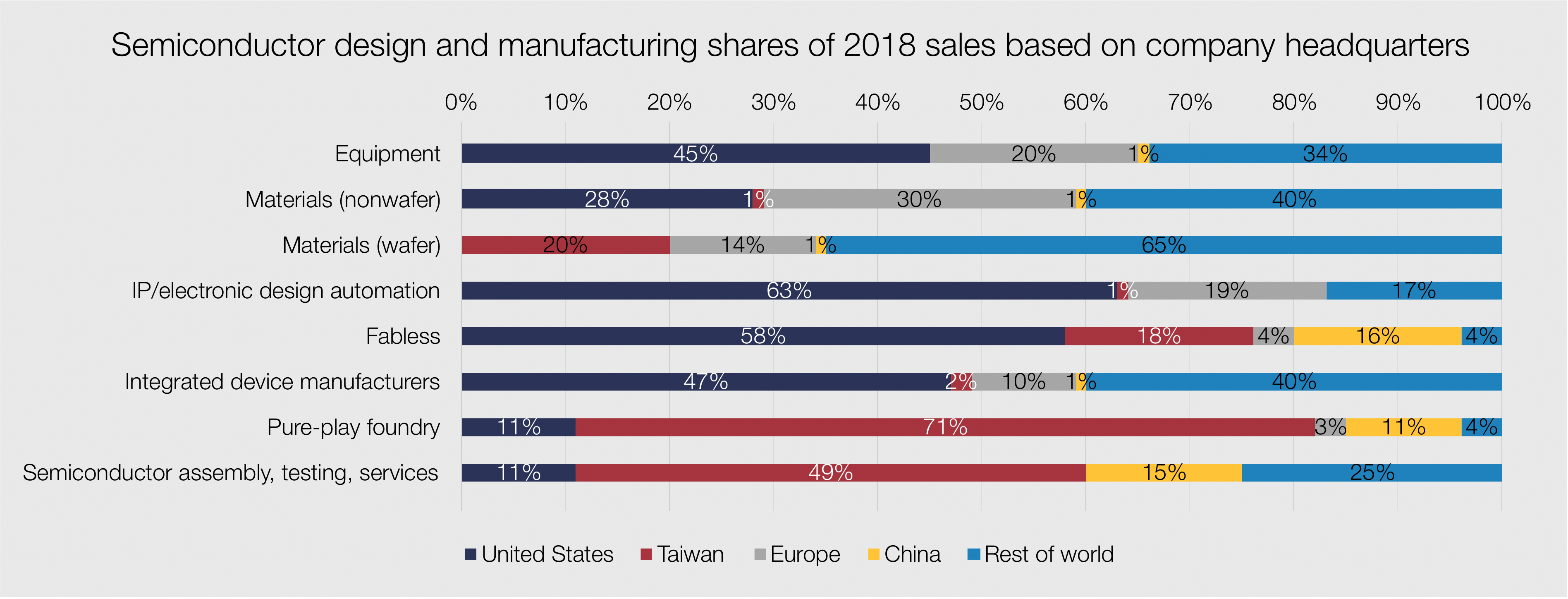

In its attempt to do this, the Commission estimates that the EU will need to fill an investment hole of €125 billion every year, with €42 billion, €17 billion, and €11 billion estimated to be needed annually in communication networks, semiconductors, and cloud technologies respectively. The US Government, in comparison, plans to spend $52 billion aiding semiconductor manufacturing and research in a country that already accounts for 48 per cent of world computer chip sales.

Plans are afoot for the US chipmaker Intel, whose European headquarters are in Ireland, to construct a $20 billion semiconductor factory within the EU, a project that it says could be spread across the continent into multiple EU states. The company is currently said to be looking for a site of circa 1,000 acres that could support up to eight chip fabrication facilities. The plan is to initially establish two fabrication facilities with costs of $20 billion over the first 10 years, but the company has predicted total investment if up to $100 billion.

Intel’s fabrication facility in Ireland is something of a leader in the manufacturing of chips in the European context.  Few facilities in Europe currently produce nodes smaller than 22 nanometres, but the Irish Intel site is currently producing 14 nanometres chips and is seeking to incorporate 7 nanometres chips as soon as possible. However, this still leaves Europe behind the capabilities evident in Asia, with TSMC in Taiwan currently building a factory for the manufacturing of 3 nanometres chips, which are expected to be up to 15 per cent faster than the 5 nanometres chips it currently manufactures and use up to 30 per cent less power.

Few facilities in Europe currently produce nodes smaller than 22 nanometres, but the Irish Intel site is currently producing 14 nanometres chips and is seeking to incorporate 7 nanometres chips as soon as possible. However, this still leaves Europe behind the capabilities evident in Asia, with TSMC in Taiwan currently building a factory for the manufacturing of 3 nanometres chips, which are expected to be up to 15 per cent faster than the 5 nanometres chips it currently manufactures and use up to 30 per cent less power.

While the presence of global chipmakers such as Intel will be one of the planks of the European efforts to ramp up chip production, the EU also has plans for boosting its indigenous chipmakers such as Infineon, Bosch, STMicroelectronics, and Dutch company ASML, the only supplier of advanced lithography machines used in semiconductor manufacturing in the world. The head start companies such as TSMC have enjoyed is sure to be felt in Europe, where the manufacture of the 2 nanometres chips set to increase in prevalence due to smart cars remains a distant possibility. Such is the lead that TSMC enjoys in operating capacity that Intel has begun to outsource some of its production to its Taiwanese rival.

However, there is reason for optimism, such as the German Government briefing European officials that it was willing to invest €3 billion of its own capital funding to reclaim production sites along the entire chain of semiconductor production.

“While global demand has exploded, Europe’s share across the entire value chain, from design to manufacturing capacity has shrunk,” von der Leyen said in her State of the Union address. “We depend on state-of-the-art chips manufactured in Asia. This is not just a matter of our competitiveness; this is also a matter of tech sovereignty. So, let’s put all of our focus on it.”