Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2022

The Northern Ireland Assembly Election in May 2022 was historic for a number of reasons but none more so than the mandating of a nationalist First Minister for the first time since the formation of the State. David Whelan writes.

While a range of notable themes emerged from the 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly Election, not least the rise of the ‘others’, the split vote of unionism and the decline of the SDLP, undoubtedly, the foremost outcome was the emergence of nationalist Sinn Féin as the largest party at Stormont.

In a legislature originally created to ensure perpetual unionist rule, a tipping of the balance is not only significant but also symbolic. The default unionist setting, historically in place since partition, can now no longer be assumed, neither internally nor externally.

Equally symbolic is the right given to Sinn Féin by the electorate to now hold the post of First Minister, if and when the Assembly returns.

Those seeking to downplay Sinn Féin’s success have pointed to no gains in the party’s seat numbers (27) and little change in first preference votes since 2017 (29 per cent compared to 27.9 per cent in 2017). Instead, the narrative is that a greater spread of votes across unionist parties, coupled with an uplift in Alliance support, led to seat declines for both the DUP (-3) and the UUP (-1).

However, such a narrative fails to recognise changing trends. The 2017 election result was widely identified as a high watermark for Sinn Féin. Less than a year before, it had lost an Assembly seat and seen its first preference vote share fall by almost 3 per cent. Fast forward to the emergence of the RHI scandal, the resignation of then-deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness and Arlene Foster’s crocodile comments in relation to the Irish language, and a fresh election saw Sinn Féin close the gap on the DUP to one seat, lifting their first preference votes on the year before.

That Sinn Féin has not only been able to hold but build upon its 2017 electoral support is significant.

In contrast to Sinn Féin’s fortunes, the DUP, as anticipated, suffered loses. Pre-election, senior figures in the party had portrayed a confidence that many recognised as feigned. Quietly, however, those same figures had hoped a decline in seats could have been avoided despite a decline in votes. In reality, the party suffered an almost 7 per cent drop in first preferences, resulting in the loss of three seats.

Interestingly and surprisingly, the decline of the DUP did little for the election fortunes of its unionist colleagues. Expectations were high that both the TUV and UUP would benefit from the DUP’s vote decline. While the TUV did see a 5.1 per cent rise in the first preference votes, frustrations were clear in the comments of leader Jim Allister MLA that his party returned only he alone to the Assembly. The TUV suffered from being transfer un-friendly, clearly seen in the context that the 65,788 first preference votes it received was not significantly less than the 78,237 first preferences votes for the SDLP, who returned eight MLAs.

In contrast, the UUP faces a dilemma. The party may have only lost one seat, but it was operating from a low base of a largely poor run of elections and its loss of almost 2 per cent of first preference votes, under new leadership and in the context of DUP in-fighting, raises questions about the party’s appeal to the electorate in its current form.

Undoubtedly, the biggest gainer of seats and votes in May’s election was the Alliance Party. Gaining nine seats and increasing its share of first preference votes by 4.5 per cent to 13.5 per cent, the party, which did not have a mandate for an Executive minister in the last term before leader Naomi Long MLA negotiated the justice portfolio, benefited heavily from transfers from the UUP and SDLP, have upset the power-sharing by designation model set up under the Good Friday Agreement.

The ‘other’ designation allowed for under the power sharing agreement was arguably not designed to accommodate such a large bloc.

The loss of two Green Party MLAs, including party leader Clare Bailey, marked a loss of the party’s total cohort of seats.

Transfers

While much analysis focuses on first preference votes as an indicator of party success, of equal importance to a party’s final tally is whether it is transfer friendly. Highlighting this, only 21 of the 90 MLAs elected in May 2021 had a sufficient number of first preference votes to meet the quota and to be elected at the first count.

Interestingly, the DUP was the most transfer friendly party, receiving 26 per cent, compared to the SDLP’s 20 per cent, Alliance’s 17 per cent, UUP’s 13 per cent and Sinn Féin’s 9 per cent.

Parties running multiple candidates often distort transfer data, with the majority of their transfers coming from party colleagues. However, of note is the fact that most of the DUP’s transfers came from the TUV (40 per cent), most of the SDLP’s transfers came from Alliance (28 per cent), while the Alliance Party had a broad appeal to voters of the UUP (23 per cent), Sinn Féin (21 per cent) and the SDLP (16 per cent).

Gender balance

The 32 female MLAs elected in May 2022, more than one-third of all members (35.6 per cent), represents a record number and a significant increase on the first post-Good Friday Agreement Assembly figure of just 13 per cent females.

A total of 17 more female candidates stood in 2022 than in 2017, meaning that females made up over 36 per cent of all candidates. Female representation in the Assembly chamber will increase slightly from election results, given that DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson MP has once again opted to co-opt Emma Little-Pengelly MLA into an Assembly seat.

Future

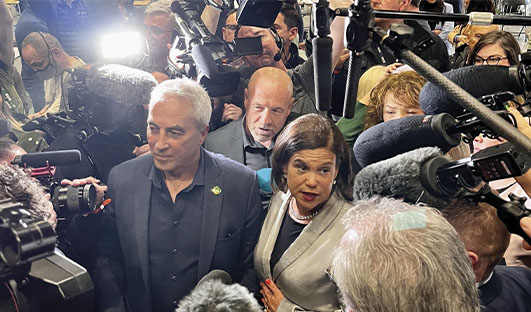

On Friday 13 May, MLAs gathered in Stormont for what would usually be the launch of Assembly business via the election of a Speaker and deputy speakers. In protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol, the DUP intends to not participate in establishing a working Assembly and Executive, meaning that all other MLAs are essentially locked out. In failing to support the election of a Speaker, the party essentially paused the operation of the Assembly.

Similarly, the Executive cannot meet without a First and deputy First Minister. The DUP said it would not nominate ministers to Stormont’s governing Executive, meaning that ministers from the last mandate are currently acting in a caretaker capacity.

Under changes to the Northern Ireland Act brought forward by the British Government amid the last collapse of Stormont, following an election, there is a six-month window for an Executive to be formed before a fresh election is triggered. The DUP has set a high bar of demand for radical changes to the Protocol and even the UK Government’s plans to domestically legislate changes to the Protocol, against the advice of the EU, might not go far enough to meet demands.

If so, Northern Ireland may face a fresh Assembly election in early winter.