The biodiversity crisis: An EU perspective

Brian MacSharry, Head of Biodiversity and Ecosystems at the European Environment Agency (EEA), says that “the narrow focus on economic growth as a measure of progress is incompatible with tackling the biodiversity crisis”.

Working at a European level, MacSharry provides a thorough analysis of biodiversity throughout the continent. “In more intensive agricultural areas, we see that the habitats are generally poorer. We see some areas – particularly in eastern and southern Europe – which can be generally better due to their different land use,” he states, adding that, “what we are seeing is not a pretty picture”.

“We have the emergence of a better situation in northern Europe. This will change in the next few years with climate change. We have also seen a change in practices in Romania and Bulgaria where land use is becoming somewhat more industrialised.

“The trend going back to the 1880s shows that sea levels and temperatures are clearly going in an upward trajectory, and not in a good way. That means that the oceans are getting more acidic, which is a problem as the shells and skeletons of key elements of the food system, such as pteropods, are being weakened, and will eventually be dissolved as our waters continue to become more acidic.”

Looking at the bigger picture, with a focus on the marine environment, MacSharry outlines the dangers posed to global society if ecosystems continue to collapse at current rates. “The entire fundamentals of the food chain in the marine environment will be changed as a result.

“When that goes, we have to ask ourselves what is going to feed all those other animals in the marine environment.”

The importance of biodiversity

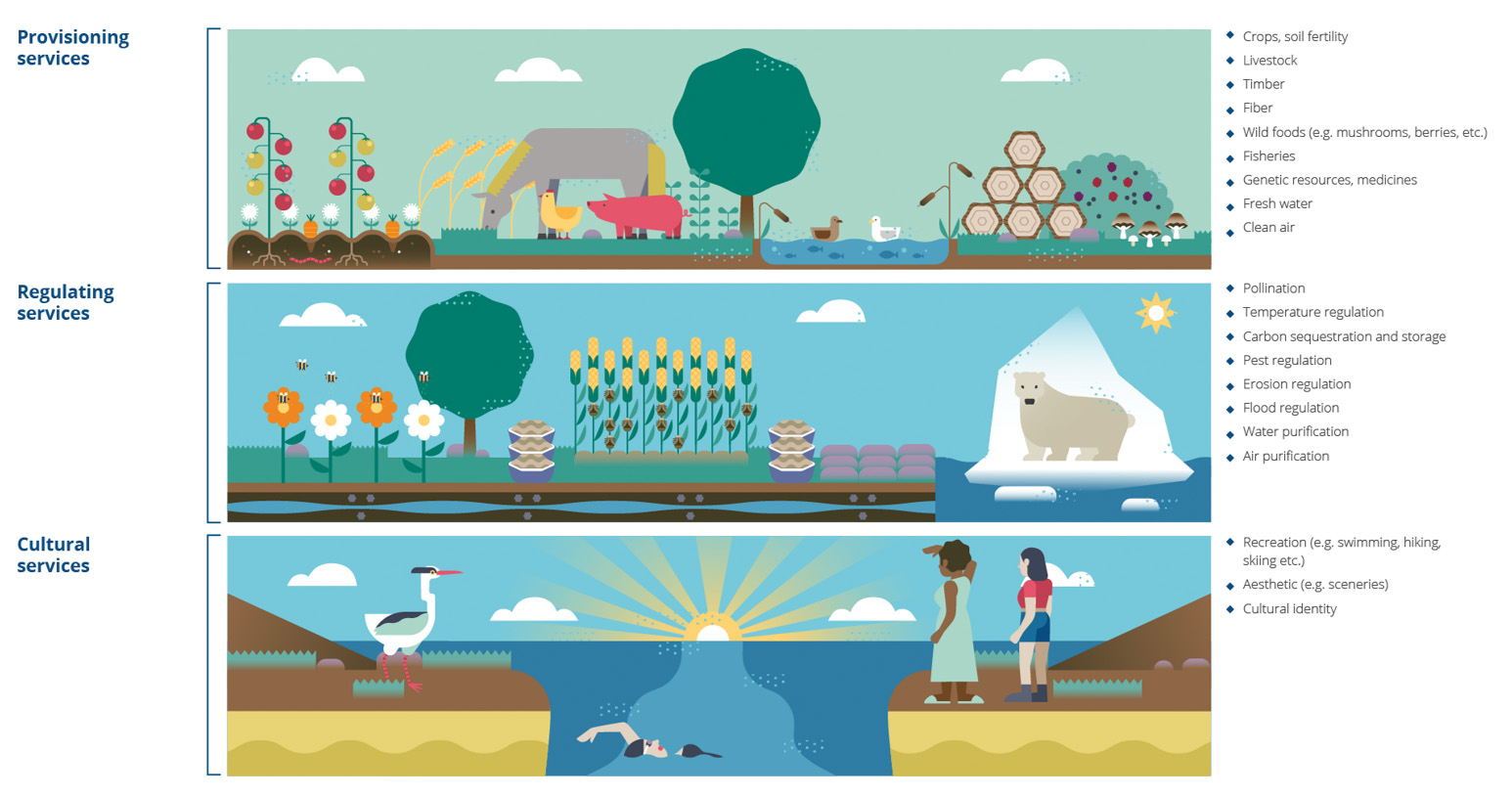

MacSharry emphasises the importance of a healthy biodiversity system, and the level of expenditure being produced by the current poor state of biodiversity throughout Europe. “In the EU, 84 per cent of crop species and 78 per cent of our wild flower species depend on animal pollination,” he explains.

“€15 billion of the EU’s annual agricultural output is directly attributed to insect pollinators. If we got rid of our insect pollinators, it would mean that we have to spend €15 billion a year to supplement those resources.”

He further explains: “In terms of valuing biodiversity, our current model of GDP does not take anything I say about biodiversity into account. It is a fundamentally broken model.”

MacSharry points to the Dasgupta Report, which analyses the incompatibility of the current GDP-based economic model with tackling the biodiversity crisis.

The Dasgupta Report states: “Nature’s worth to society – the true value of the various goods and services it provides – is not reflected in market prices because much of it is open to all at no monetary charge.

“This is not simply a market failure, it is a broader institutional failure too. Many of our institutions have proven unfit to manage the externalities. Governments almost everywhere exacerbate the problem by paying people more to exploit nature than to protect it, and to prioritise unsustainable economic activities.”

Current initiatives

MacSharry believes that the current regulations, directives, legislation, and strategies are necessary but not sufficient for tackling the biodiversity crisis, and that a much bigger problem lies in the implementation of said initiatives.

“At an EU level, one of the biggest drivers is the Biodiversity Strategy, published in 2020. Having worked in biodiversity for over 20 years, I felt that this strategy was the most ambitious but also simplest strategies I have ever seen.

“It was pretty upfront in what it wanted to achieve. It said that biodiversity was key to the survival of our society, and will form part of the European Green Deal. It was broken down into four key elements: Protection; restoration; transformative change; and the global governance of the oceans.”

He further reiterates the importance of viewing biodiversity targets as qualitative rather than quantitative, pointing to the commitment to have a network of 30 per cent of EU maritime area as marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2030, which he describes as “as welcome as it is needed”.

On restoration, MacSharry outlines the importance of a law, rather than a Directive, being used to enforce the measures outlined. “We have seen that when this is arranged on a voluntary basis, it is not working. At a European level, we decided that we needed a new law to sort these things because the number of legislative aspects we had to push for countries was ridiculous.

“The Habitats Directive has been around since 1992 but very few countries have actually fully implemented it. The amount of time going into arbitrating these measures and disputes between countries just shows that it has not been taken seriously across the continent.”

Flipping the narrative

MacSharry concludes by reiterating his central point on the incompatibility of the GDP-based economic model with solving the biodiversity crisis. “Instead of incremental change we need systemic and transformational change. Nature should not be considered as outside the system but as the fundamental system.

“We need to move away from short-term thinking and shift our mindsets to embrace the long term. The European Green Deal drives this transformative change of strong systemic logic, linking across sectors, society and embracing a longer time horizon,” he asserts.

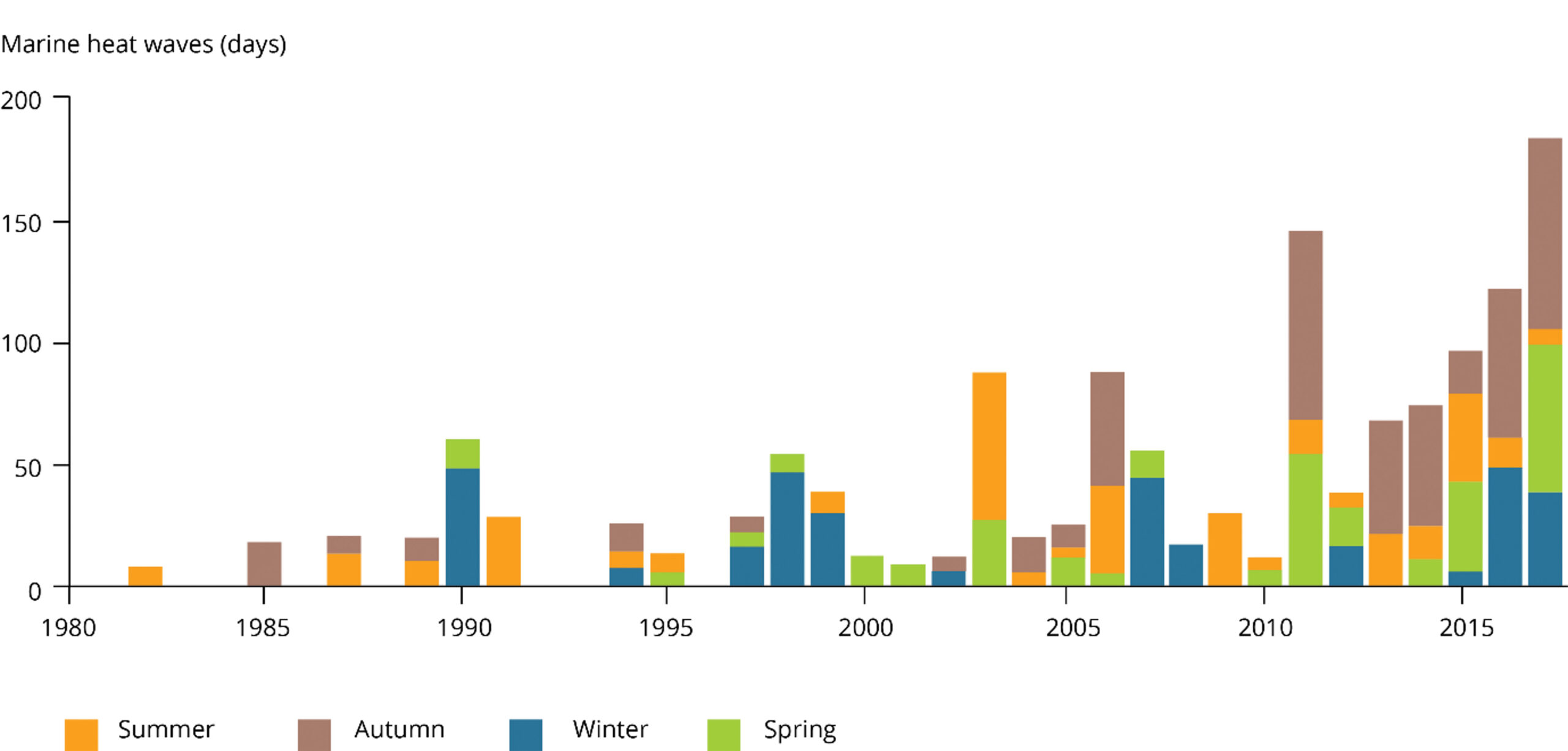

Heatwaves since the 80s