Centenary of republican hunger strikes

Cormac Moore, a historian-in-residence with Dublin City Council and a columnist with The Irish News, reflects on the centenary of the 1923 hunger strike undertaken by some 8,000 republicans – male and female – held by the Free State after the cessation of the Civil War.

On 24 May 1923, the anti-Treaty IRA called an end to the Civil War by ordering its members to dump their arms. Tensions remained high, however, between Free State supporters and republicans. Violence continued beyond May, including extra judicial killings by Free State forces which went unpunished, including that of Noel Lemass, brother of future Taoiseach Seán, whose body was found in the Dublin Mountains in October 1923 shot, mutilated, and badly decomposed.

As there was no negotiated settlement, with republicans dumping arms to fight another day, instead of surrendering them, there was no large-scale prison releases with 12,000 people still imprisoned or interned after the war had ended, including 500 women.

The Free State Government resisted all calls to release republicans long after the conflict was over. To release the prisoners, the government argued, would risk the reopening of hostilities. The Free State Government chose to release the prisoners and internees in stages, according to the danger they felt they posed. Some republicans were even arrested after the dumping of arms in May, including Éamon de Valera who was arrested in August 1923 as he was about to address an election rally in Ennis in County Clare.

At the general election in August, republicans did far better than they or anyone else expected, winning 44 seats with an increase of 5.6 per cent of the vote share from the last general election in June 1922. Of the 44 elected, 18 were in prisons or camps around the country. With such electoral support for republicans, their chances of early release were lessened.

Faced with an uncertain future and based in prisons and camps where the conditions were considered very poor, morale amongst republicans was at an extremely low ebb. There was also undue pressure on them to ‘sign the form’ and accept the legitimacy of the Free State.

It was in these conditions that republicans decided to embark on a large-scale hunger strike to highlight their plight. The hunger strike had been a potent weapon during the War of Independence for otherwise powerless prisoners through either forcing the British to back down or as a powerful means of propaganda if hunger strikers were to pay the ultimate sacrifice and die. The death of Thomas Ashe through force-feeding while on hunger strike in 1917 and that of Terence MacSwiney from a hunger strike in 1920 were key moments in the independence struggle against the British. No other event in Ireland generated more international media coverage than the death and funeral of MacSwiney in 1920, including Bloody Sunday and the burning of Cork city.

The hunger strikes from the War of Independence and the hunger strikes carried out by republican women during the Civil War were major factors in republicans deciding to embark on their hunger strike in October 1923.

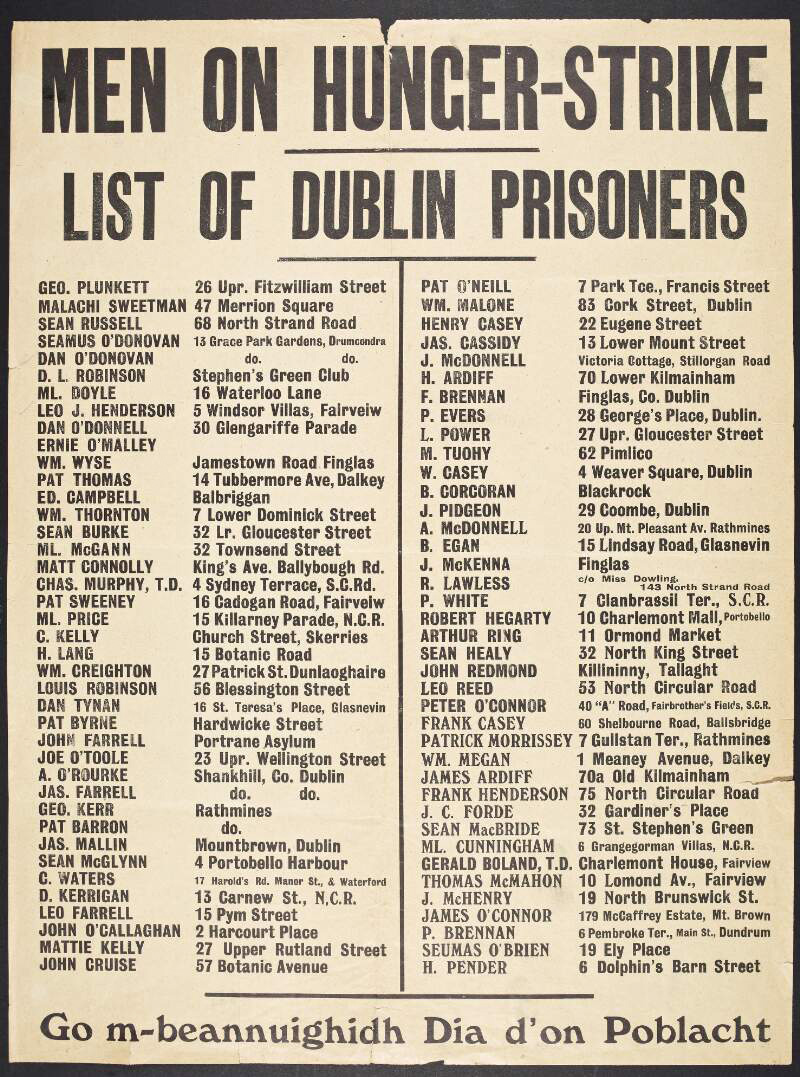

Without any coordinated plan within the republican movement, prisoners in Mountjoy Jail took the initiative themselves and went on hunger strike on 13 October 1923, as a protest of prison conditions and the continuation of their incarceration. They were soon followed by prisoners in other camps with about 8,000 men and women ultimately going on hunger strike.

The huge numbers who went on hunger strike was in many ways at the root of the campaign’s failure. There was criticism by some who felt the number of people on hunger strike was way too high, believing they should be limited to carefully selected individuals, people who could be relied upon to follow the hunger strike to the brutal end.

The strike was poorly planned from the outset with people unclear of its ultimate goal, when it could be called off, by whom, and on what grounds. Both the political and military leadership of the republican movement were unaware of it before it started in Mountjoy, including de Valera. He was not asked to take part in the hunger strike. While people were allowed to participate or not in the hunger strike, many felt under pressure to take part, a ‘sort of moral conscription’.

“The hunger strike had been a potent weapon during the War of Independence for otherwise powerless prisoners through either forcing the British to back down or as a powerful means of propaganda if hunger strikers were to pay the ultimate sacrifice and die.” Cormac Moore

There was much agitation from public bodies, including from bodies who were supporters of the Free State, to release the prisoners. Despite the pressure, the government stood firm and did not yield to the hungerstrikers, people who had not renounced violence against the Free State, people who had refused to accept its legitimacy.

With the Free State Government standing firm and many of the hunger strikers faltering, within three weeks of the commencement of the hunger strike, many started to take food which caused a domino effect, making it more and more difficult for others to stay on it. Large numbers came off the strike long before it was officially called off 41 days after it commenced on 13 October, without any guarantee of being released.

The strike was finally called off on 23 November, but it was too late for two men, Denis Barry and Andy O’Sullivan who died on the 20 and 22 November respectfully.

Although many prisoners and internees were released from October to December 1923, with 2,647 prisoners released in November alone including all women who were incarcerated, many remained in jail until the summer of 1924, particularly those considered the leaders of the republican movement. Upon release, republicans faced bleak prospects, demoralised, and defeated. Some, whose health never recovered from the hunger strikes, died early deaths. Others, unable to gain a livelihood, were forced to leave Ireland and try and eke out a living elsewhere.