The health and economic cost of antimicrobial resistance

Ireland will be one of the EU/EEA countries most exposed to a fall in labour market output if current antimicrobial resistance trends continue, a report by the OECD has found.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is essentially the body’s ability to reject the medical influence of antimicrobial agents in medicine, is acknowledged as one of the greatest public health threats globally.

AMR is responsible for more than 35,000 deaths per year in the EU/EEA, a figure projected to rise to 79,000 deaths annually moving towards 2050, unless the issue is addressed.

In Ireland, unless resistant infections are eliminated, AMR is estimated to claim the lives of more than 169 people each year.

One in every five infections across the OECD is now caused by superbugs, fuelled by high levels of inappropriate use of antimicrobials. Despite policy efforts to optimise antibiotic consumption, average sales of all classes of antibiotics have been rising by nearly 2 per cent since 2000.

Current trends suggest that third-line antimicrobials, the last resort drugs against difficult-to-treat infections could be 2.1 times higher by 2035 in the OECD compared to 2005.

Alongside excess deaths, AMR and the failure to properly address it have large economic costs. The OECD estimates that the cost of treating complications due to resistant infections can exceed €26.5 billion every year (adjusted for purchasing parity) across 34 OECD and EU/EEA countries.

It is estimated that an additional 32.5 million days are spent in hospitals per year to treat the consequences of AMR, while the impact of AMR on workforce participation and productivity is estimated to be equivalent to €33.8 billion, corresponding roughly to one-fifth of the gross domestic product in Portugal in 2020.

Advocating the One Health framework, a multisectoral approach that promotes coordinated action across human and animal health, agrifood systems, and the environment, the OECD says: “The AMR pandemic is already here. While Covid-19 has led to efforts to prevent and control the spread of infections, there is no room for complacency in the fight against AMR. Results from the OECD analysis demonstrate that policy action that is grounded in a One Health approach is urgently needed to tackle AMR.”

Ireland published its first national action plan on antimicrobial resistance in 2017, with a second One Health National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2021-2025 currently in delivery.

Some progress has been made. According to the OECD, resistance proportions for 12 antibiotic-bacterium pairs increased from 2015 to 14.9 per cent in 2019, however, this is still significantly below the EU/EEA average (21.3 per cent), and resistance proportions are projected to decline to 14.1 per cent by 2035 in Ireland.

Ireland’s average 33.1 defined daily dose (DDD) per 1,000 persons per day in 2025 was above the 24.1 EU/EEA average. While projections are for antibiotic consumption to decrease to 30.8 per day by 2030, they remain above the projected EU/EEA average of 23.2.

Ireland exceeds the World Health Organization’s target for access antibiotics to make up at least 60 per cent of national consumption, with first and second-line therapies with lower resistance potential making up nearly 67 per cent of all antibiotics consumed in 2015.

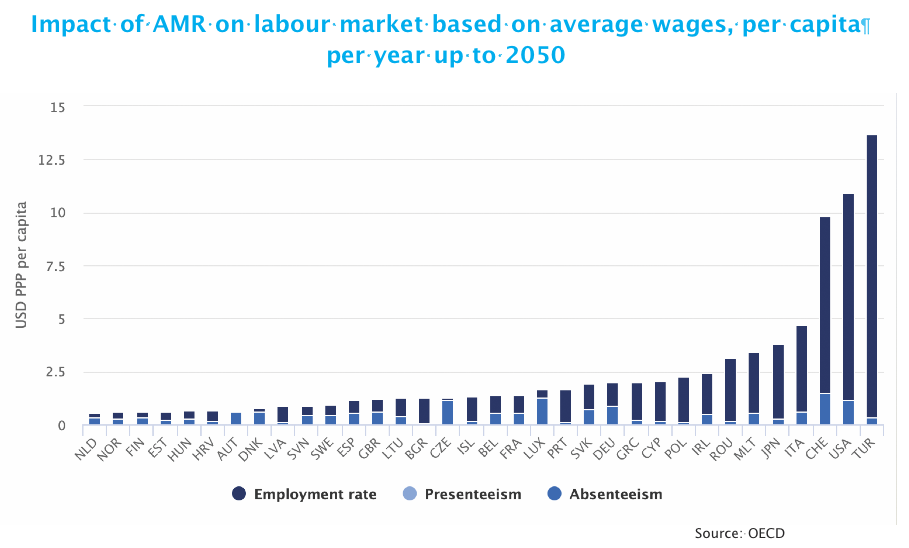

Giving emphasis to the need to address the challenge, the OECD research highlights how estimated declines in workforce productivity translate into considerable financial losses for nations.

AMR is estimated to depress workforce productivity by around €5.3 billion per year by 2050 in the EU/EEA, and Ireland is second only to Italy in estimations to incur the greatest losses in per capita labour market output across the EU/EEA countries.

The OECD examined the impact of different policies including a mixed policy package that would involve the scaling-up of five policy priorities across sectors such as improving antibiotic stewardship, delayed antimicrobial prescription, and enhancing food safety.

The estimations are that if Ireland was to invest €5 per person annually in a mixed policy package, annual gains would be:

Summarising that the cost of inaction to tackle AMR is high, the OECD says that alongside national action plans, policy priorities for action lie in bolstering nationwide implementation of programmes for infection prevention and control; investment in more robust surveillance systems; ensuring greater compliance with regulatory frameworks; and development of new antibiotics, vaccines and diagnostics.

“By addressing many of the existing policy gaps, all 11 policy interventions modelled by the OECD are estimated to generate substantial health and economic gains. In particular, the following interventions yield the highest gains,” the report states.

“Scaling up investments in One Health packages of actions against AMR is affordable, with a return on investment significantly greater than implementation costs… The health and economic benefits of implementing One Health policies as policy packages far exceed the benefits accrued by implementing these policies in isolation.”