TRADE UNION DESK: What should be done about the pension age?

In response to the Report of the Commission on Pensions, the Government agreed to keep the pension age at 66, writes Laura Bambrick, spokeswoman on pensions at the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU).

Raising the pension age to 67 and again to 68 in 2028 had become a key battleground during the 2020 general election and the most important deciding factor for voters, after health and housing.

Support for the Siptu-led Stop67 campaign has not waned. Public opinion polls show two-thirds (66 per cent) of voters are in favour of keeping the pension age at 66. Support is strongest among 18- to 34-year-olds, suggesting that the intergenerational fairness argument to justify hiking the pension age does not have the support of almost seven-in-10 (69 per cent) of the intended beneficiaries.

Unions have never denied the challenge Ireland’s ageing population presents for the future sustainability of the State pension and for younger generations if no action is taken now.

However, the projected scale of this challenge has moderated significantly over successive actuarial reviews of the Social Insurance Fund, as noted by the Comptroller and Auditor General in its 2023 audit of the State’s accounts. Nonetheless, a yawning gap remains between anticipated pension expenditure and the Fund’s resources.

Keeping the pension age at 66 will mean higher and new social insurance contributions and other pension policy reform.

Revenue raising

But there is scope for revenue raising. The yield from employer social insurance contributions alone would need to almost double just to reach the EU average. Already a 0.7 per cent increase in employer, employee, and self-employed social insurance rates, to be gradually rolled out, has been flagged.

From October 2024, a worker on average earnings will pay 90 cent more a week in PRSI when the first of five yearly increases kicks in. The additional income raised (€240 a million a year) will grow the Social Insurance Fund surplus (€4.3 billion in 2024) to support the retention of the State pension age at 66 and fund a new pay-related contributory benefit for unemployed workers.

Intergenerational solidarity and fairness must be a two-way street. At the moment, PRSI is not levied on any earned and unearned income of those aged 66 and over. This blanket exemption needs to go. Why should, for example, landlords stop paying PRSI on their rental income profits when they turn 66?

However – and on this unions are clear – care must be taken when ending the PRSI exemption on over 66s to ensure that it does not unfairly impact certain groups of pensioners, such as pre-1995 civil and public servants who have no entitlement to the State pension, or unduly weaken the incentivise to work or save for a secure retirement.

Policy reform

Landmark pension reform is already well advanced to move away from a one-size-fits-all pension age to a European-style flexible pension age to give workers more choice.

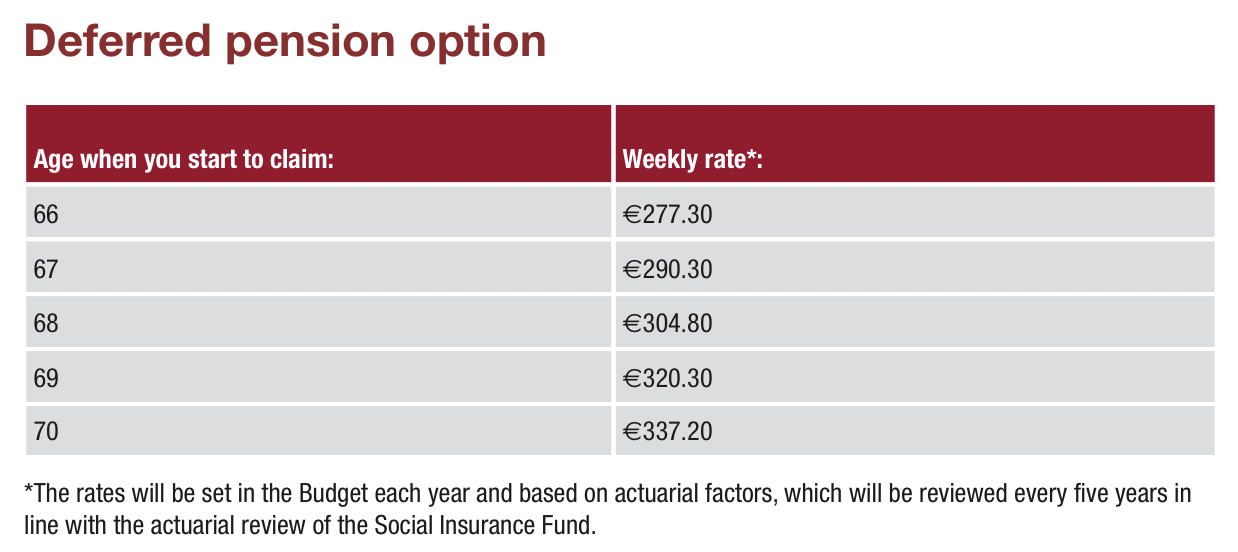

From January 2024, when a worker reaches age 66, they can now choose to delay claiming their State pension up to age 70 in return for a higher weekly payment. This deferred pension option will also give people who are short the required number of social insurance contributions the choice to work longer to build up their PRSI record.

Unions have long argued there is a sizeable and growing number of workers who are forced to retire earlier than they would wish because of the age of retirement in their employment contract, typically 65. Legislation ending forced retirement before the State pension age is due to go to Cabinet for approval soon.

Meanwhile, early access to the State pension for workers with a long work history and social insurance record – having worked from a young age typically in physically demanding jobs – is under consideration.

In Germany, for example, workers who have paid social insurance for at least 45 years can claim the State pension at 63, three years earlier than the pension age and with no deduction in the weekly payment.

A flexible pension age to facilitate and reward longer working lives is a much fairer policy to pushing up the pension age for everyone.

Where next?

Political realities mean that the pension age is far from a settled question. The most consistently popular party in the polls, Sinn Féin, says it should be cut from 66 to 65 – a pension age which only very few people qualified for before it was abolished in 2014. As such, another general election fought on the pension age may be just around the corner.