The Troubles(ome) history of British policy in Northern Ireland

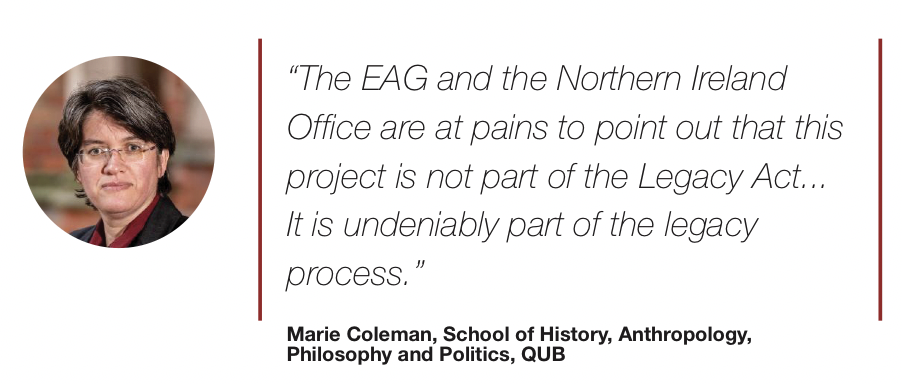

As an academic historian, I have serious reservations about the so-called ‘public history’ of British policy in Northern Ireland announced recently by the British Government, writes Marie Coleman, Professor of 20th century Irish history at Queen’s University Belfast.

An Expert Advisory Group (EAG) has been appointed to oversee the process and hire five historians to write this history. The absence of leading scholars of ‘the Troubles’ from the EAG is notable. None of the authors of recent books on subjects including negotiations to end the conflict, government censorship of media coverage, and the role of the British army, are on the EAG. If they were not invited it begs the question ‘why not’? If they were asked and turned it down that is a significant vote of no confidence in the project.

There are no academics currently working in Northern Irish universities, nor any from a northern Catholic and/or nationalist background, on the EAG. If the experts so far have refused to take part how much success will the EAG have in recruiting suitably qualified candidates to fill five posts?

Ethics

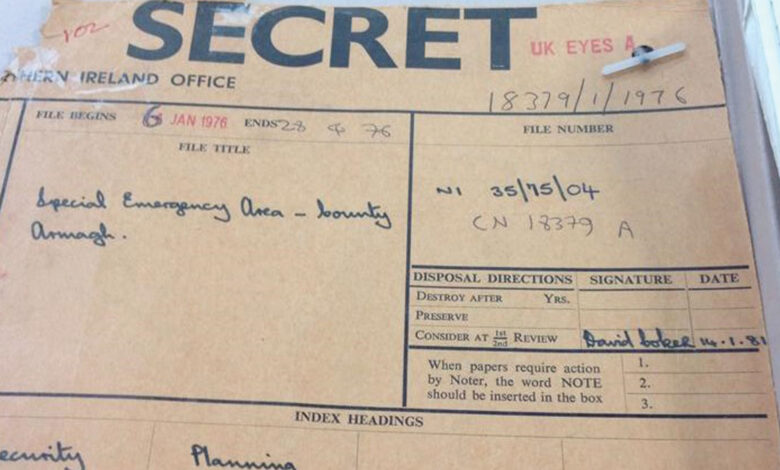

A glaring error of omission in the published Terms of Reference of the EAG is any reference to ethics. To comply with standard norms of ethics and integrity in research, academics are expected to “keep clear accurate records to allow for verification”. This project will have “the opportunity to access otherwise closed materials which may never be released”. In such circumstances, how can any of the work be verified if nobody else ever sees the documents again?

Ethical approval would also be required if any oral history element is involved, which would be an expected methodology in such a contemporary subject. The controversial ‘Boston College tapes’ project is a spectre that haunts research into ‘the Troubles’ and is now widely used by those of us who teach ethics to university students as an example of how not to conduct research.

‘Public history’

The project calls itself a ‘public history’, but it is no such thing. ‘Public history’ is a recognised subdiscipline of academic history, defined by the United States’ National Council on Public History as ‘the many and diverse ways in which history is put to work in the world. In this sense, it is history that is applied to real-world issues’.

For this project to qualify as a ‘public history’ one, it would need to embed a public history element, such as close collaboration from the outset with an institution like a museum, in its core methodology. Plans to engage ‘with media outlets, community groups, and the wider cultural sector to promote public awareness and understanding of the period of the Northern Ireland conflict’ does not qualify this project to call itself ‘public history’.

I

I

‘Official history’

If this is not a ‘public history’ what is it? It is an ‘official history’, part of a long-standing British government series dating back to 1908. The EAG has asserted its independence and intention to reject any efforts of government control. Yet, there are ways in which governments exert control over official histories about which the group can do little.

The publication of Michael Howard’s official history of strategic deception in intelligence operations during the Second World War was held up on security grounds by Margaret Thatcher and could not be published until after her resignation as Prime Minister. If the Northern Ireland project were to encounter a similar obstacle a scholar could be left with no published work after five years of research, with seriously adverse effects on career advancement.

Governments can also control the narrative through restrictions on the time period studied. Keith Jeffery’s official history of MI6 concluded in 1949 because the head of MI6 considered the Cold War too sensitive to cover. Conveniently, this avoided any serious discussion of the defection of the Cambridge spies. It is notable that the Terms of Reference of the EAG refer only to studying British policy ‘during the conflict in Northern Ireland’, with no definition, chronological or otherwise, of what that means.

Legacy Act

The EAG and the Northern Ireland Office are at pains to point out that this project is not part of the Legacy Act. Yet during the debate on the bill in the House of Lords in May 2023, Dean Godson (Lord Godson) sought to have it included, a move supported by Paul Bew (Lord Bew), current co-chair of the EAG. The project was announced publicly in the same week that the Legacy Act came into force. It is undeniably part of the legacy process.

Many academics are dubious of the EAG’s confidence about being given “full and unfettered access to all materials”. Even if this is given, the Legacy Act’s denial of the same access to the families of victims is deeply problematic and in the view of some scholars at least, unethical.

The British Labour Party is likely to repeal significant sections of the Legacy Act and the current government is trying to have much of its infrastructure in place to make that task difficult. It is hard to escape the sense that this project has been rushed through hurriedly to get it set up in time. Little else could account for how poorly thought-out its provisions are.

If it is to continue, action is required immediately to clarify its title, delineate its chronological coverage, and produce a robust ethical framework. Then it will be matter of individual choice for scholars whether the lure of privileged access to archives outweighs qualms about the concurrent denial of that access to the families of ‘Troubles’ victims.