Global water scarcity reinforces need for sustainable management

With water scarcity becoming an increasing problem on every continent, achieving Goal 6 of the UN sustainability development goals (SDGs) to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all is becoming increasingly critical, write Neil Delaney, Head of Strategic Water Programmes and Jillian Bolton, Regional Lead Water Ireland with Jacobs.

Public consumers expect that water will be available for their use while water utilities demonstrate improvements to our environment through sustainable abstractions combined with responsible treatment and release. To achieve SDG 6, the water sector must continue to meet these expectations while managing the increasing challenges and pressures on global water resources from population growth, economic development, and climate change.

The global water supply crisis is well documented, with media reporting shortages globally. Shortages in Cape Town, South Africa have been widely reported, however less widely reported shortages include southwestern USA where the Colorado River no longer discharges to the sea due to over abstraction and use.

Globally, water stress levels are predicted, up to 2050, by the World Resources Institute at a national level, with ‘extremely high’ stress levels in areas of North and South Africa and parts of Asia, while Australia is tracking slightly more favourably with ‘high’ stress levels expected. Conversely, northern European countries predominantly track as having ‘low’ or ‘low to medium’ water stress levels in the same timeframe.

European challenges

While the global view appears to demonstrate a positive national picture for countries such as Ireland and the United Kingdom, within each jurisdiction regional challenges are already arising driven by climate changes to weather patterns and increased population in focused areas. The 2018 drought in Ireland resulted in water supply restrictions in targeted locations due in-part to limitations on the connectivity of our water supplies.

Overreliance on a given water source can lead to challenges and ultimately limitations due to environmental impacts as the source is needed to supply a growing population or commercial use, be that industry or agriculture.

These factors all contribute to a growing sense of urgency to create more integrated, sustainable, and resilient water supplies even in those jurisdictions predicted to continue to have adequate water supply.

Achieving this will not be resolved through one factor alone and will require urgent measures to manage the supply demand balance, including leakage reduction, to ensure alignment with wider governmental climate action plans and goals, combined with the development of new supply options to mitigate against supply restrictions in the near future.

The challenges of achieving a sustainable economic level of leakage (SELL) in countries like Ireland and the United Kingdom – with ageing infrastructure, growing urban populations, and dispersed rural settlements – are well documented. However, from a regulatory and moral imperative in the face of global water scarcity, the water sector needs to continue to progress and innovate towards this goal.

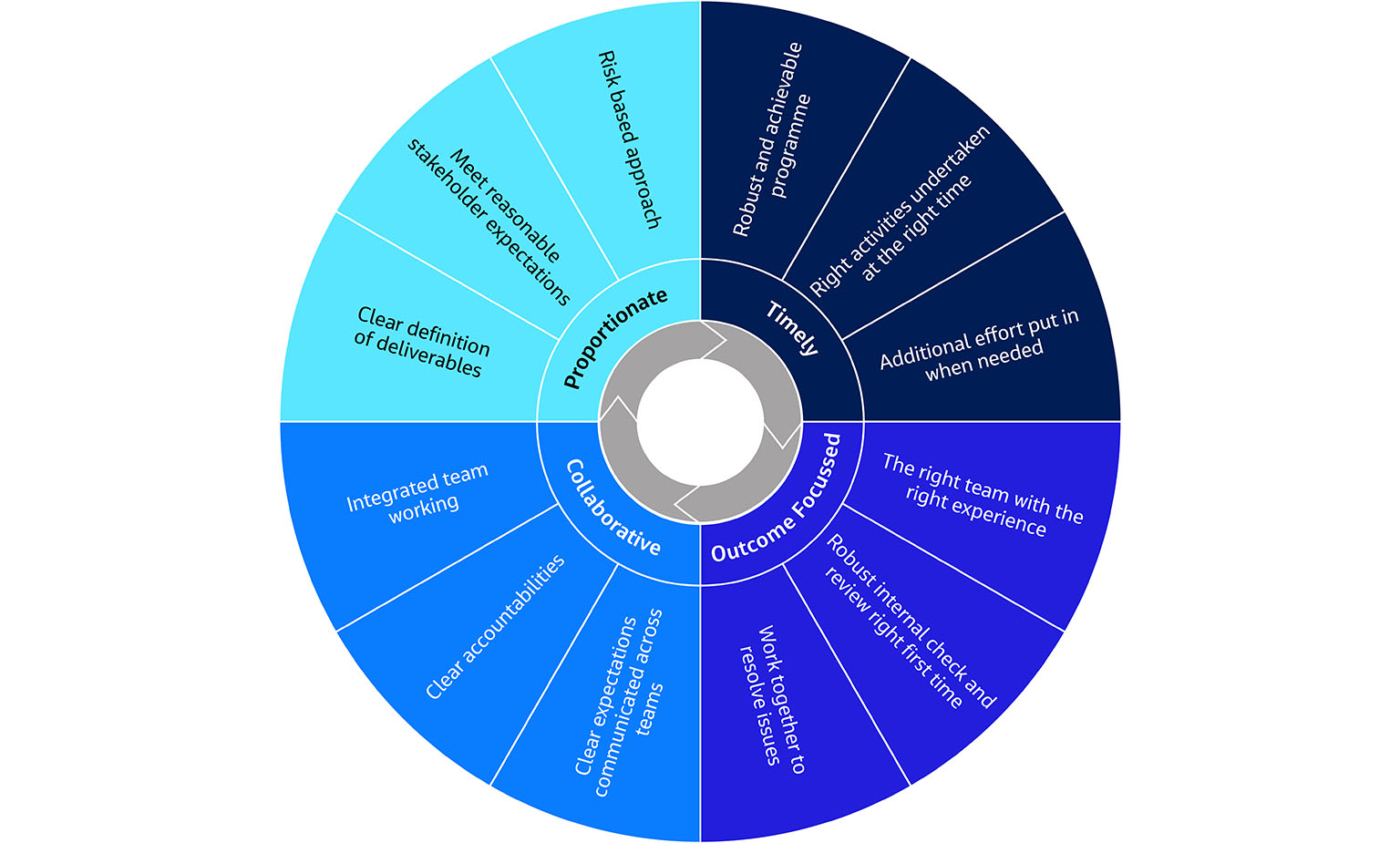

Figure 2: Collaborative, outcome-focused, proportionate, and timely approach to delivery of DCO

In addition, water consumption, whether at a personal or industry level, needs to become a priority for all, through national education, minimising our own personal use and the development and implementation – at sector and national levels – of reuse and recycling programmes in housing and high water usage industries. The Tuas Water Reclamation Plant based in Singapore shown in Figure 1, recycles water for further reuse.

For some industries, novel thinking will be required to ensure that the water required is fit for purpose; in some instances that may not be potable drinking water. For example, recycled effluent could be a suitable source for cooling waters.

Notwithstanding the achievement of long-term success in these areas, the delivery of new resilient supply options will continue to be necessary to meet the growing needs of our existing economies.

Supply and network resilience

In England, a national review suggested that when considering population growth, environmental ambitions, and climate change, the southeast will be subject to water shortages by 2040. These projections included assumptions of a 50 per cent reduction in the current leakage levels and a reduction in the per capita consumption to 110 litres per person per day – the consumption target set by Ofwat (the Water Services Regulation Authority) for users across the country.

Allowing for that, a national programme to implement Strategic Resource Options (SROs) is proposed at a cost of approximately £17 billion. These options will store, transfer, and recycle water to provide resilience across the country. The need for which has been proven through regional and utility water management plans, which have been progressed through statutory and non-statutory consultation processes.

The Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (RAPID) was set up in 2019 to help accelerate the development of this new water infrastructure and design future regulatory frameworks for its operation. This regulatory body is made up of the three water regulators: Ofwat, the Environment Agency, and Drinking Water Inspectorate. They will provide a seamless regulatory interface, working with the water industry to promote the development of national water resources infrastructure that is in the best interests of water users and the environment. The goal is to ensure this infrastructure can be implemented in a timely manner to ensure resilient water supplies across the country.

Development consent orders

These substantial projects will use the Development Consent Order process to achieve planning. This is similar to the Strategic Infrastructure Development (SID) regulations in Ireland and elevates the planning decision to a national level. As with all planning processes, and key to the effective and timely delivery of critical public infrastructure, robust consultation is required to ensure that public input is incorporated into the ultimate decision making. In this regard, the process includes public consultations for each SRO submission and for the regulatory determinations for each project approval ‘gate’ as defined by RAPID. These consultation stages augment previous consultation on establishing the need for the projects, ensuring the public, statutory and non-statutory consultees and interested parties are fully aware at all stages of the process, with their knowledge and inputs considered.

In addition, there is an acknowledgement that this infrastructure is larger in scale than anything undertaken in the UK water sector in the last 40 years. Therefore, a robust process must be undertaken given the scale of impact both to those who will be impacted by its construction and operation and those who will be impacted if it is not provided. Figure 2 demonstrates the collaborative approach required to achieve success across major planning projects.

Strategic Resource Options (SROs)

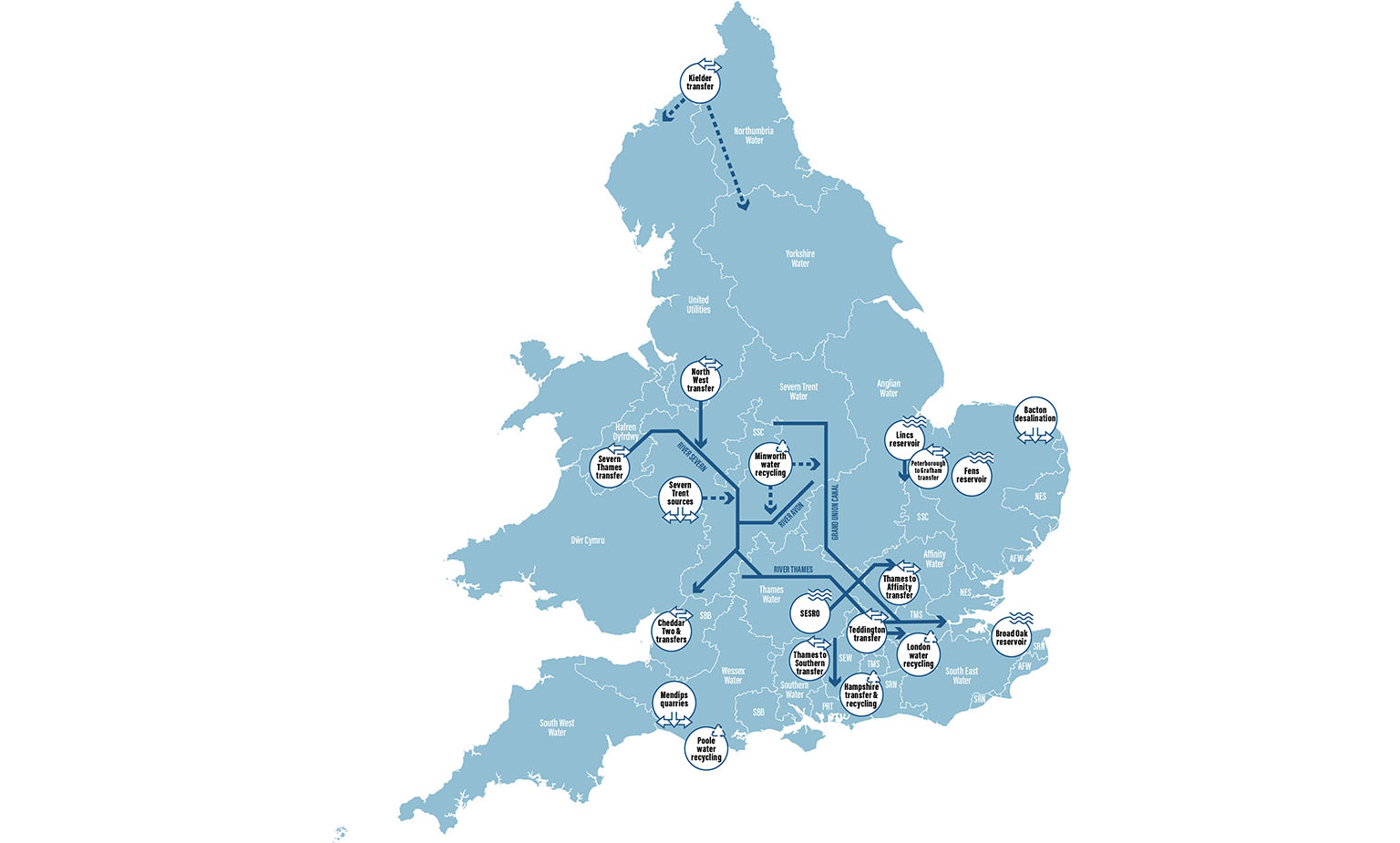

Figure 3 illustrates the scale of the UK Strategic Options (SRO) programme. Examples of these SROs in England include:

- the Southeast Strategic Reservoir Option, which will store 150Mm3 of water and cover a surface area of 6.5km2, at a cost of approximately £2.7 billion;

- the Severn to Thames Transfer, which will transfer water during times of drought from the River Severn (the largest river in the UK) 80km to the River Thames (the second largest River in the UK), with various water sources added to the Severn in times of low flow; and

- London Water Recycling, where effluent from existing wastewater treatment works would be treated through an advanced water recycling plant (AWRP) or a tertiary treatment plant (TTP) and discharged to the River Thames, where it can be abstracted as a raw water resource in times of low flow.

Figure 3: Representation of the UK Strategic Resource Options (SRO) Programme

Global Water Recycling Projects

Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) is an example of where the development of recycling has been effectively implemented alongside a national education programme to make this a valued asset, providing national water supply resilience, and avoiding overreliance on international trade to import water. Recycling programmes demonstrate sustainable and efficient use of the available water supply within a given jurisdiction.

The reality is that all water is reused as there is truly no new water on the planet. Organisations such as PUB have safely treated used water to augment their water supplies for decades. The technology is there; however the real challenge is developing a thoughtful way to implement potable reuse programs to meet public expectations.

PUB has also developed NEWater, its own brand of ultraclean, high-grade reclaimed water. Singapore has five NEWater plants which further purify treated, used water to produce this NEWater, which has passed more than 150,000 scientific tests and meets and surpasses World Health Organization and US Environmental Protection Agency standards for drinking water.

With the country’s water demand expected to double by 2060, Singapore is looking to use NEWater to meet more than half of this future water demand. Thanks to an integrated water management strategy nationwide, Singapore is one of just a few cities in the world to harvest its stormwater and practice large-scale water reuse as part of its diversified water supply approach.

Figure 1, shown previously, represents an animation of the Tuas Water Reclamation Plant (WRC) in Singapore, a key component of the Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS) Phase 2, which collects used water for further reclamation in NEWater

“Many countries are now predicting a significant upturn in investment in water infrastructure over the coming decade.”

Supply chain collaboration for success

The provision of a resilient water supply is considered equal to a resilient power supply and strong transportation infrastructure and is therefore a key consideration for foreign direct investment when locating into a given country or region. In several countries, the funding for power and transportation has been strong over the past few decades, however, water and sanitation has not attracted the same level of investment. Globally, water investment has been insufficient and, as demands from users and regulators grow, there is a significant expenditure required to meet expectations. This will be a challenge to the water sector.

Many countries are now predicting a significant upturn in investment in water infrastructure over the coming decade, placing a strain on the sectoral supply chain to ensure that these aspirations are met. New procurement models, new partnerships, and new thinking in how we implement water infrastructure will be required, alongside a change in our relationship with the water that we use on a daily basis. The latter will require national public campaigns to highlight water use ratings for various activities and products.

Financing and procurement are two of the most critical challenges within major projects globally. These two factors play an integral role in defining project success, especially long-term cost and risk. Funding and delivery models can help create the right cost structures and improve procurement results through competitive tenders or bids. For water utilities to develop resilient, sustainable major water infrastructure projects between 2025 and 2030, in addition to major standalone schemes, the industry requires effective procurement and delivery mechanisms. Delivery partners must build effective, multidisciplinary teams that use cross sector insights and global teams to drive productivity. The Direct Procurement for Customers (DPC) model in the United Kingdom, which is similar to Design Build Operate and Finance, offers a tailored solution and multiple client benefits, especially within the fast-growing water sector.

From a sustainability perspective, addressing our water consumption behaviours while continuing to drive down and maintain leakage rates require priority to minimise waste, costs and carbon generation. This approach, combined with the successful and timely delivery of national water storage, recycling, and transfer projects and programmes, will ensure countries with manageable water stress levels, like Ireland and the United Kingdom, can continue to meet the needs of their population, through the provision of safe, sustainable water supply nationally, meeting the requirements of SDG 6 while enabling long-term economic growth.

For more information:

T: +353 1 202 7718

E: Jillian.Bolton@Jacobs.com

W: www.jacobs.com