Is Ireland on track to meet its retrofit targets?

While significant progress has been made towards the State’s residential retrofit targets, these are challenged by financial, structural, and policy-related obstacles. Accelerating delivery will depend on a collaborative approach write Ciara Ahern, senior lecturer, and Elihu Essien-Thompson, software engineer and data analyst, with TU Dublin.

In 2019, the European Commission published the European Green Deal, setting an ambitious target for European Union (EU) member states to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050. This directive mandates a 55 per cent reduction in net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030, relative to 1990 levels.

In Ireland, the residential sector is a significant contributor to GHG emissions, primarily due to the age of its housing stock; approximately 67 per cent of European homes were constructed before 1980, predating modern thermal building regulations. With a replacement rate of less than 0.1 per cent annually, most of these dwellings will still be in use by 2060, underscoring the critical need for energy-efficient refurbishments.

To address this, Ireland’s Climate Action Plan (CAP) was introduced in 2021, aiming for 500,000 residential retrofits to achieve a Building Energy Rating (BER) of B2 or higher, and the installation of 400,000 heat pumps by 2030. These initiatives are paramount to reducing the residential sectors carbon footprint. Ireland’s Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) or Building Energy Rating (BER) database plays a central role in this strategy, providing empirical data on a dwelling’s retrofit status. As of the third quarter of 2024, over 1.26 million EPCs have been issued in Ireland, covering 66 per cent of the nation’s 1.86 million occupied dwellings.

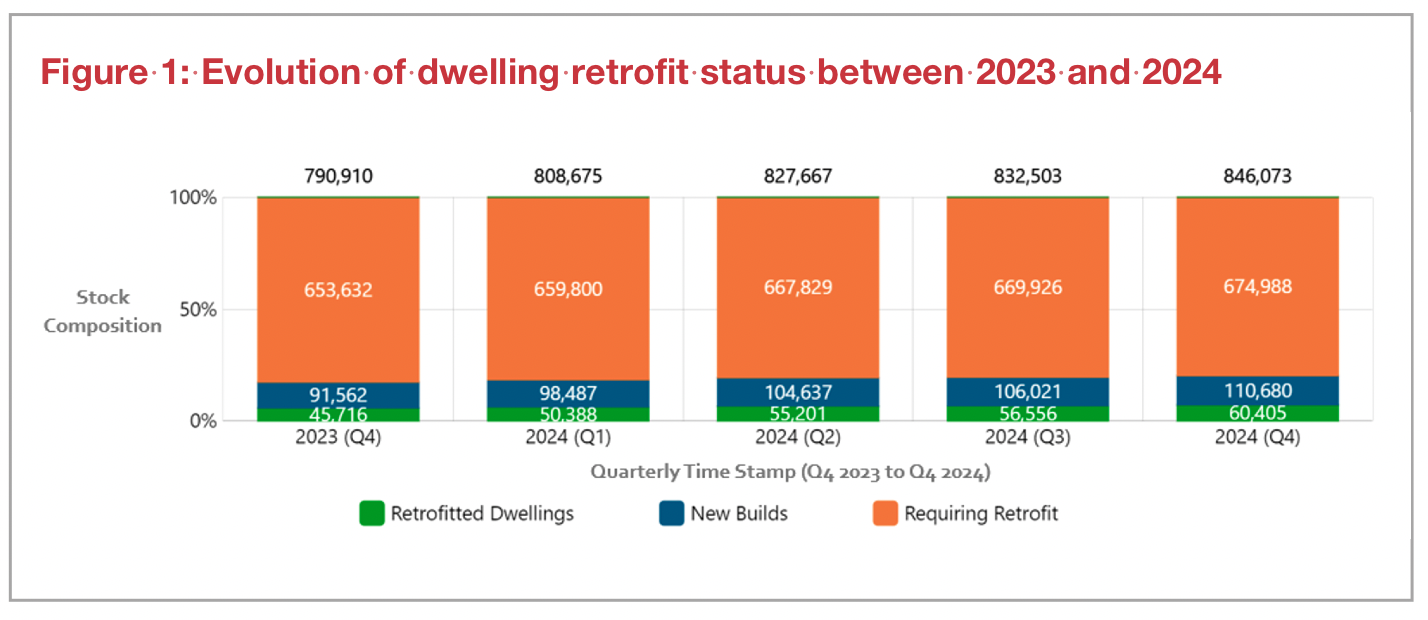

The Irish Building Stock Observatory (IBSO), established in 2022, has been instrumental in processing and validating this data, offering quarterly snapshots that reflect the refurbishment status of Ireland’s housing stock, as shown in Figure 1.

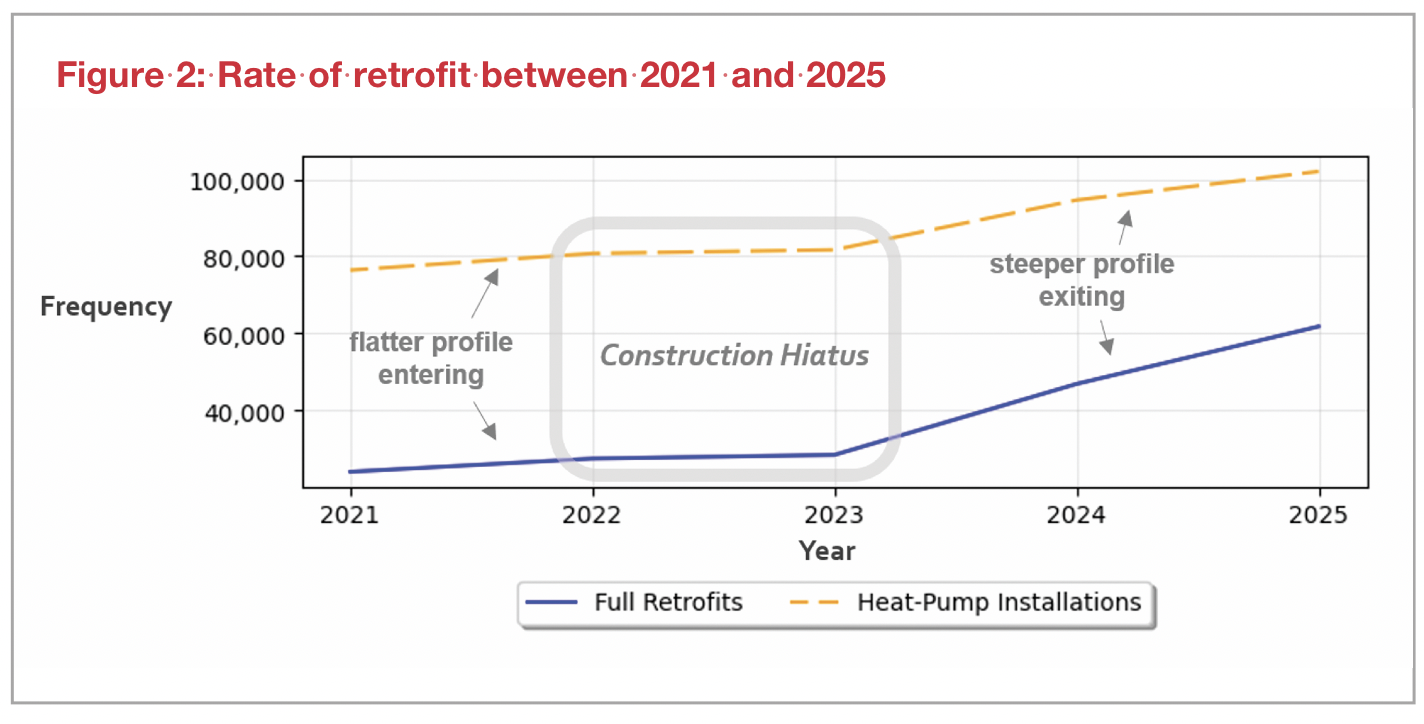

Analysis of IBSO data from 2020 to 2024, and as shown in Figure 2, reveals a notable trend: while there was a decline in retrofit activities during the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent construction hiatus caused by global events, a significant rebound occurred post-2023. This resurgence indicates a growing momentum towards achieving the CAP’s targets.

However, projections based on logistic market modelling suggest Ireland is projected to meet its B2 retrofit target by 2032, slightly exceeding the original 2030 goal by two years. The heat pump installation target, however, presents a more significant challenge, with forecasts estimating that the 400,000-unit goal will not be achieved until 2042 under current trends.

These projections account for market growth phases, including acceleration, saturation, and eventual plateauing. The data suggests that the initial surge in retrofits post-2023 will slow as the easier-to-upgrade dwellings are completed, requiring more aggressive policies and incentives to maintain momentum and address complex retrofit cases.

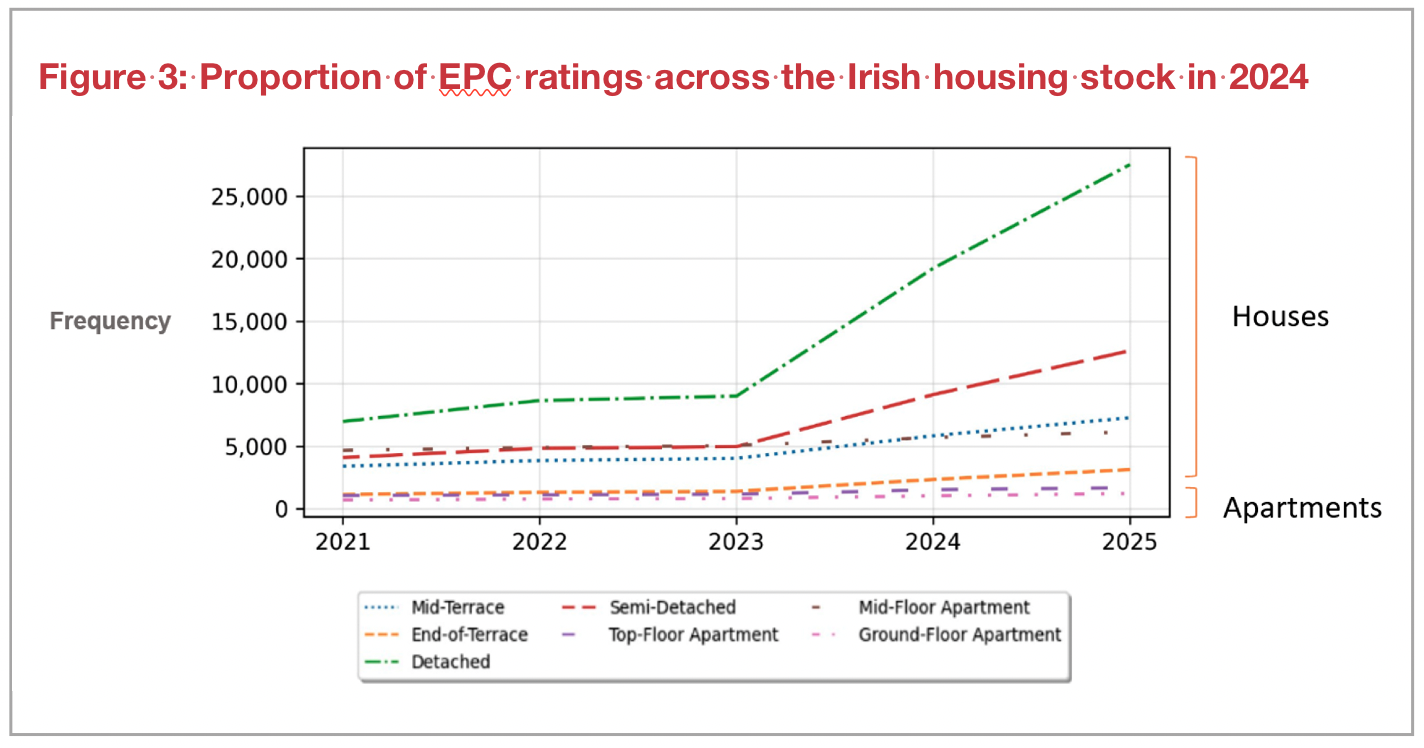

A deeper dive into retrofit rates by dwelling typology reveals disparities. As shown in Figure 3, detached and semi-detached houses have seen the most significant increases in B2 retrofits, with 295 per cent and 209 per cent growth respectively between 2021 and 2024. In contrast, apartments, particularly mid-floor units, exhibit lower retrofit rates. This discrepancy is partly due to the inherent energy efficiency of apartments, which benefit from shared walls and reduced exposure, but also points to potential challenges in mobilising retrofit initiatives within multi-unit dwellings.

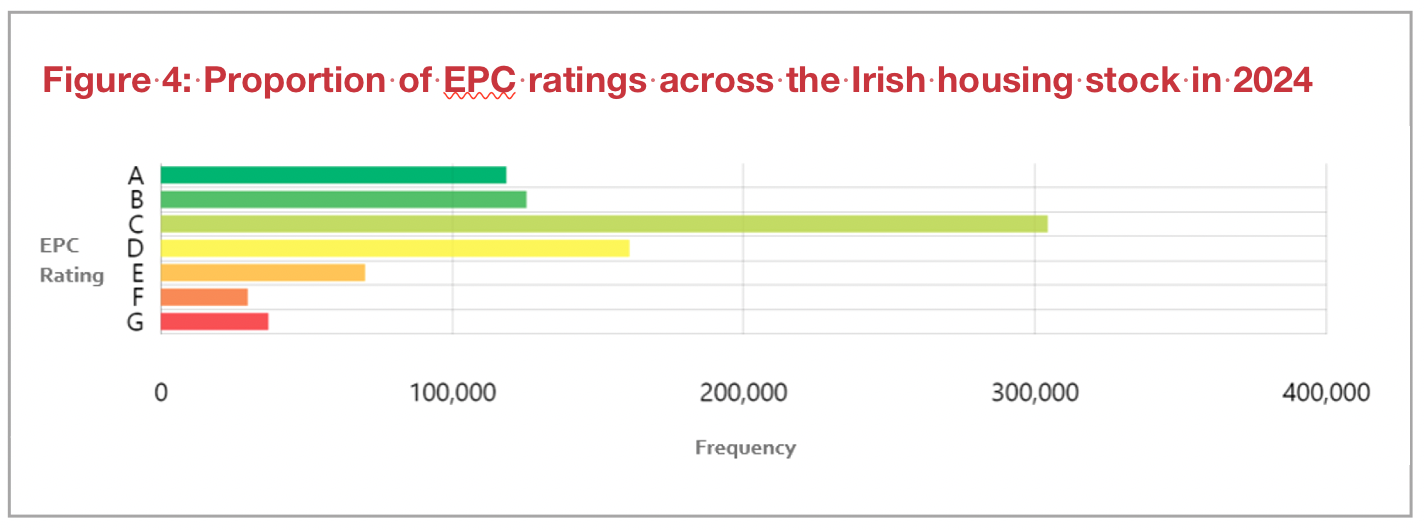

Financial considerations play a pivotal role in retrofit decisions. As can be seen from Figure 4, C-rated homes dominate the EPC landscape. Homeowners in C-rated dwellings often face a “comfort barrier”, perceiving their homes as sufficiently comfortable with manageable energy costs, thus diminishing the incentive for extensive retrofits.

Moreover, while achieving a B2 rating can be costly – often requiring significant investments in insulation, window replacements, and heating system upgrades – access to green mortgages and preferential financing is typically available starting at a B3 rating. This financial structure may inadvertently discourage homeowners from pursuing the more ambitious B2 upgrades.

Case studies further illustrate these challenges. For instance, as shown in Figure 4, a 1980s three-bedroom semi-detached house underwent three retrofit scenarios to a B2 energy rating that vary in cost and complexity: one involving the replacement of an open fire with a stove and window upgrades, the second scenario remove the fire entirely without window enhancements, and the third assessed principally using PV panels to achieve the B2 energy rating.

All approaches achieved a B2 rating, but none met the Heat Loss Indicator (HLI) threshold of 2.3 W/k/m2 required for heat pump grants. Notably the homeowner would have been able to achieve the green mortgage threshold at a significantly lower investment cost than that of meeting the B2 policy target.

To bridge the gap between current progress and the 2030 targets, several strategies are recommended:

- Coherent financial incentives: Aligning grant structures and green financing options to reward deeper retrofits can motivate homeowners to aim for B2 ratings specified in the Climate Action Plan.

- Targeted outreach: Focusing on dwelling types with lower retrofit rates, such as older apartments, through tailored programs can address specific barriers these units face.

- Policy adjustments: Aligning the B2 target with the HLI index to create a pathway to heat pump adoption more accessible. This could be supported by a higher level of financial incentives to encourage homeowner adoption.

In conclusion, while Ireland has made commendable strides in its residential retrofit journey, achieving the ambitious 2030 targets necessitates a multifaceted approach. By addressing financial, structural, and policy-related challenges, and fostering collaboration among stakeholders, Ireland can accelerate its progress towards a more energy-efficient and sustainable housing stock.