A good news story about Irish healthcare?

Richard Layte explores how increasing the prescription of cardiovascular medicines led to a reduced mortality rate among older Irish people and how the early use of primary care prevents more serious illness later in life.

Richard Layte explores how increasing the prescription of cardiovascular medicines led to a reduced mortality rate among older Irish people and how the early use of primary care prevents more serious illness later in life.

Life expectancy for older people in Ireland has been increasing steadily since the 1980s. Despite this, Irish life expectancies for the over sixty-fives lagged seriously behind the EU average as recently as the mid-1990s. But Irish death rates for the over sixty-fives dropped dramatically between 2000 and 2005, moving Ireland closer to the European average. Whereas between 1996 and 1999 death rates (from all causes) in Ireland had fallen by just over 5 per cent, between 2000 and 2004 the decrease was over 26 per cent.

What lies behind this rare and welcome good news story? An article by researchers from the ESRI and the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Trinity College Dublin (Explaining structural change in cardiovascular mortality in Ireland 1995-2005: a time series analysis) sets out the background to this sharp fall in death rates, and examines how the greater use of effective drug therapies contributed to this result.

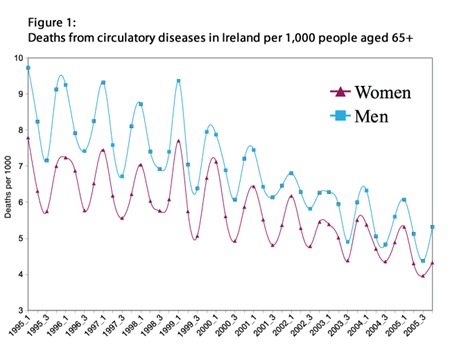

The fall in mortality was particularly pronounced for diseases of the circulatory system such as heart disease and strokes where there was a 30 per cent reduction between 2000 and 2005. This was an extraordinary development that, if sustained, would have had huge implications for the provision of services to older Irish people such as pensions and health care. Looking around for clues some noticed that the fall in the rate of deaths was particularly pronounced in the winter months (see figure 1). Ireland sees 21 per cent more deaths in the depths of winter than in high summer (almost twice the Danish proportion), largely from the interaction of low temperature with existing cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, so analysts initially looked to global warming for an explanation.

Analysis of weather trends showed no warming during recent winters so what could explain the drop in death rates?

Prescribing Patterns

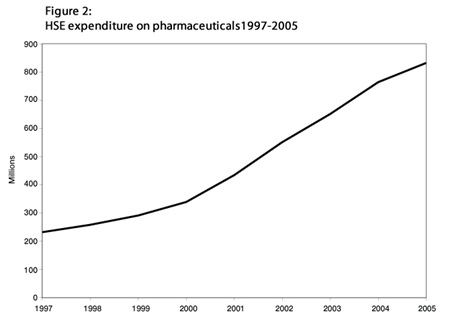

One possible explanation may lie in changing prescribing patterns in Ireland. Since 1995 there has been a steady year- on-year increase in the number of items prescribed but around the turn of the century, the rate of prescribing increased significantly. Between 1995 and 1999 the number of items per patient increased by 26 per cent, whereas between 2000 and 2004 the increase was 53 per cent. Doctors also appeared to be prescribing more expensive medicines after 1999. The average cost per item increased by 64 per cent between 1995 and 1999, compared to 122 per cent between 2000 and 2005 even though pharmaceutical inflation had been negligible. The increasing volume and cost of pharmaceuticals prescribed meant steeply increasing HSE expenditures on pharmaceuticals after 2000 (see figure 2). A large part of this increase in items and expenditure was due to the increased prescribing of cardiovascular medicines. These had been increasing since the late 1990s following the Irish Cardiovascular Strategy but rates of prescribing grew quickly following the introduction of the medical card for over 70s in the July of 2001 and the subsequent increase in use of primary care by older people. Between 1999 and 2003 the volume of ace inhibitors prescribed almost doubled, the volume of beta blockers more than doubled, while the volume of statins prescribed more than trebled.

Could this change in prescribing explain the sudden fall in mortality among older Irish people? The timing of the change in prescribing seems plausible and it is known that drugs such as beta blockers and ace inhibitors can counteract some of the strains placed on the cardiovascular system by cold weather.

Using data on patterns of mortality across age and sex groups and prescribing patterns by year and quarter between 1995 and 2005, the researchers showed that there was indeed a change, or ‘structural break’ in the pattern of mortality in Ireland around the turn of the century. After 1999 for instance, excess winter mortality fell by 9 per cent among Irish men and 6.8 per cent among Irish women. Further analysis showed that this change could be explained by increased prescribing of beta blockers, ace inhibitors and aspirin medications.

Such falls in mortality are a cause for celebration and mean thousands of people are alive today who would otherwise have died. It is likely that these cardiovascular medications are also contributing to the significant decrease in disability among older Irish people experienced in recent years. The effect also underlines the important role played by primary care in the Irish health care system. As well as keeping many people alive, this prescribing also prevented many older Irish people from experiencing the heart attacks and strokes that would have otherwise occurred and in so doing, saved the Irish hospital system a great deal of resources. This is a good example of the importance of treatment protocols since some of the change is attributable to the cardiovascular strategy and secondary prevention. However, the change in prescribing was most marked after the change in eligibility for the medical card. This shows the benefits that accrue from providing primary care free at the point of delivery and keeping prescribing fees modest. Early use of primary care prevents more serious illness later and helps to move healthcare from expensive public hospitals to relatively less expensive primary care settings. This research also suggests that taking medical cards from some over 70s and the recent introduction of the 50 cent prescribing fee may have a negative impact on health and mortality in Ireland. Drug budgets have increased strongly in recent years and there are good grounds to believe that we can and should reduce prescribing expenditure. In doing so we should not lose sight of the fact that medical treatments both save lives and help people live productive lives with chronic illnesses that would have been profoundly disabling two decades ago.