Alan Kinsella and Irish Election Literature

Since 2009, the Irish Election Literature website has hosted a vast collection of material from elections, referenda, and other campaigns. Curator of the Irish Election Literature archive and producer of the The Others podcast, Alan Kinsella sits down with Ciarán Galway to discuss his archive’s origins, trends in political literature and his initial foray into podcasting.

When and why did you begin collecting political posters, leaflets, and ephemera?

The first material I got would have been in February 1982 outside a polling station. It was a different time and canvassers could congregate outside the polling stations. My parents went inside to vote, my brother and myself were outside and Barry Desmond [a former Labour TD and government minister] signed a canvas card: ‘To Alan, best wishes, Barry.’ Over the years, Barry has given me great stuff.

There was a second election in November 1982, and I asked friends and family members to collect literature for me. Over time, that collection grew. In the mid-2000s, I realised what I had: a relatively large archive that wasn’t limited to one group or one party. As well as an election archive, it also includes protest material.

Initially, I felt awkward asking people to keep the material coming through their letterbox for me. Later, I remember going into my local library and offering to exhibit the material and they looked at me as though I had two heads as they felt there would be little interested. That put me off for a little while.

“Having been digitalised online, the archive has become a useful resource for people interested in politics.”

Then, in 2014, I had my first exhibition in the National Print Museum. That planted a seed. I initially thought it would only attract political nerds, but it had a far wider appeal due to the nostalgia. Material relating to particular issues, such as divorce or abortion, have a great appeal from a social history perspective. When I exhibit anti-abortion literature, young people in their teens, 20s and early 30s look at it and are completely agog. It was a very different Ireland.

How much engagement do you have with the parties and candidates?

My local councillors, TDs and also senators are very good to me and I get stuff in the post from various elected representatives. The flipside of that is that they know their material is being archived. If you think of politics as a job, how much material is kept? The volume of leaflets and posters produced is significant, especially over a long political career. Commonly, they simply bin everything after each election because it’s useless. Often then, at the end of a career, there is very little evidence of that election material left. They never think it’s going to end, but often it does so abruptly with an election. So, if I have something spare, I’ll send it to them.

Having been digitalised online, the archive has become a useful resource for people interested in politics. If people uncover something, they know they can send it to somebody who will archive it and if it’s a very interesting piece, it will potentially be exhibited.

How many individual pieces do you estimate are in your collection and how are they catalogued?

I have stuff from all over the place. It’s mostly Irish, but I collect material from across the world. I got loads of stuff recently from cousins in the States from the various elections and referenda there.

“Much political literature has become depersonalised and a lot more decentralised.”

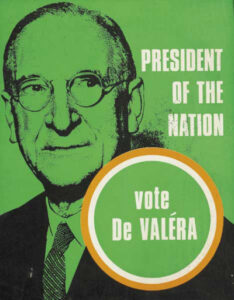

I would estimate that I have around 50,000 leaflets and 1,000 posters. Some of the oldest date back to Éamon de Valera’s campaign during the 1917 East Clare byelection. It’s fascinating because of the historical significance of that election, including the limited franchise at the time and the subsequent journey of de Valera’s defeated opponent Patrick Lynch who Dev later appointed Attorney General for Ireland. It’s possible to trace the economic and social history of Ireland through the material.

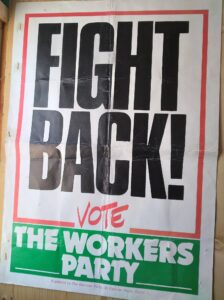

Cataloguing depends on the size of the party. If it is a small party such as Democratic Left and Independent Fianna Fáil or other parties which didn’t exist for long such as the Sligo/Leitrim Independent Socialist Organisation, Aontacht Éireann, I would catalogue them separately. Elsewhere, material is catalogued by constituency or county as best as I can. I always hate Constituency Commission reports because it undoes me. I also have a couple of boxes dedicated to far-left material and so on. I have stickers separate to leaflets and all the other oddities would be stored separately as well.

How has political literature evolved over the years?

Much political literature has become depersonalised and a lot more decentralised. Everyone gets style guides sent out from HQ. Typically, they now have a picture of the party leader, a picture of the candidate and an identical message on the back. It’s not often even locally tailored. Over time, it has become far less verbose as parties have realised that attention spans are limited.

“I particularly love the posters from the 1970s and the 1980s; when colour came in there was a lot more variety.”

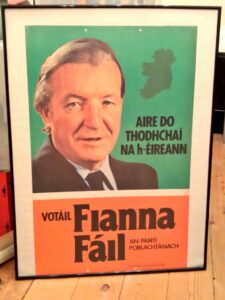

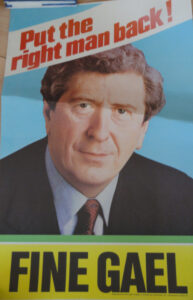

At the same time, in 2002, Fine Gael performed very poorly and so in the subsequent election in 2007, the party’s material was a lot less centralised and it would have included a lot more personalised material. The same happened in 2011 with Fianna Fáil when candidates prioritised personalised material over party branding. With Sinn Féin, during the 1980s and early 1990s, republican credentials, such as time spent in Portlaoise would have been emphasised, whereas by the early 2000s, the focus had shifted to business and community credentials.

Previously, from the 1950s through to the 1990s, the material ubiquitously included profiles of the candidates; where they went to school, how many children they have and their involvement within the community. Things like that. You don’t get that anymore. Similarly, it’s rare enough that people include pictures with their families anymore. I would assume it’s about keeping private life private and public life public.

What are some of the most interesting items in your collection?

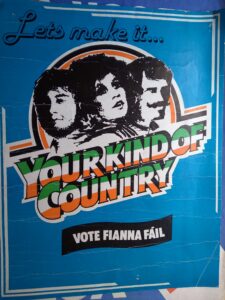

I particularly love the posters from the 1970s and the 1980s; when colour came in there was a lot more variety. Alongside posters of historical figures such as Dev, Charlie Haughey, Garrett FitzGerald and Des O’Malley, some of the odder ones in my collection are almost unique. For example, the Christian Principles Party leaflets with the slogan: “Jobs for youth, not condoms.” They are completely niche but very much of the time. I have a jumper from the Mary Robinson campaign in 1990 and it’s a piece that always gets attention whenever it’s displayed.

I particularly love the posters from the 1970s and the 1980s; when colour came in there was a lot more variety. Alongside posters of historical figures such as Dev, Charlie Haughey, Garrett FitzGerald and Des O’Malley, some of the odder ones in my collection are almost unique. For example, the Christian Principles Party leaflets with the slogan: “Jobs for youth, not condoms.” They are completely niche but very much of the time. I have a jumper from the Mary Robinson campaign in 1990 and it’s a piece that always gets attention whenever it’s displayed.

“I have a lot of material from small parties and groups that have some interesting histories, so I thought I would start telling them.”

The Simon Harris wet wipes are gas. The last time, he was giving out oranges with stickers on them. In 2014, a dentist called Keith Redmond was running for Fine Gael and handed out tubes of toothpaste, so I have some of them. I have a Sinn Féin harmonica. I have lollipops, beermats, coats, umbrellas, jackets, a dog coat from Deirdre O’Donovan’s campaign with the slogan ‘no tall tales, just common sense’. There’s no end to it.

What provoked you to produce your new podcast on some of the more obscure parties and people in Irish politics?

I had much more spare time with the lockdown and began looking for a niche. Then I thought of one. I have a lot of material from small parties and groups that have some interesting histories, so I thought I would start telling them.

I’m always looking at election supplements, examining the independents to find out who they are and why they’re running. Then I try to get an idea of the small parties. There’s a pattern of people setting up small parties believing that they are going to change the world. Take, for example, the Community Democrats of Ireland, formed in 1979, which named Noël Browne and Seán Dublin Bay Loftus as candidates without even consulting them.

I’m always looking at election supplements, examining the independents to find out who they are and why they’re running. Then I try to get an idea of the small parties. There’s a pattern of people setting up small parties believing that they are going to change the world. Take, for example, the Community Democrats of Ireland, formed in 1979, which named Noël Browne and Seán Dublin Bay Loftus as candidates without even consulting them.

It’s a bit of a rabbit hole. People always look at the poll toppers, the headlines and at who won or lost an election, they never look deeper into the peripheral issues of the day. That’s why I started producing the podcast.

Recently, I produced a podcast on South West Donegal Hospitalization Committee candidate Eunan Curristan. Eunan was one of the first hospital candidates and he set a trend for the decades ahead in Monaghan, Tullamore, and Roscommon. Other more obscure parties, like Lia Fáil, are remembered by very few people and yet they were completely off the wall.

Córas na Poblachta and Ailtirí na hAiséirghe are another two. In the 1940s, there was so much happening and so many crackdowns; they were all smashed when Clann na Poblachta took almost everything that wasn’t Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Labour.

Córas na Poblachta and Ailtirí na hAiséirghe are another two. In the 1940s, there was so much happening and so many crackdowns; they were all smashed when Clann na Poblachta took almost everything that wasn’t Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Labour.

There is also the phenomenon of agrarian parties. The Farmers’ Party of the 1920s and early 1930s died out and then Clann na Talmhan emerged in the late 1930s. The Farmer’s Party had represented the big farmers and had no seats west of the Shannon, whereas Clann na Talmhan were the opposite and represented the small farmers and were much more successful west of the Shannon.

What are your ambitions for the future?

I don’t believe printed literature will disappear entirely in the move towards a ‘paperless’ era. Some of it inevitably will, but most will remain. People will continue to hand out material, canvass and meet people. Candidates can’t not canvas.

Like everyone else, I had plans for 2020 which didn’t materialise. Just before all the lockdowns, I delivered an exhibition and a talk at the Limerick Spring Festival. I was due to drive down and then there was a storm, so I got the train and literally just had a case of material that I was able to populate a room with. It was brilliant.

Like everyone else, I had plans for 2020 which didn’t materialise. Just before all the lockdowns, I delivered an exhibition and a talk at the Limerick Spring Festival. I was due to drive down and then there was a storm, so I got the train and literally just had a case of material that I was able to populate a room with. It was brilliant.

I will be producing a book at some stage and I’ll keep the podcast going because I have tonnes more material. Hopefully, I’ll be able to bring back the exhibitions; that’s the big ambition. I love doing exhibitions because I can physically show off the material, interact with people, and invariably you get to establish new connections for material. That’s really important and I’m looking forward to getting back post-pandemic.