Annette Connolly: The economic and fiscal landscape in 2020

While rapid growth in the Irish economy continues, in recent years it has largely been determined by multinational-dominated sectors. Meanwhile, both domestic and macroeconomic risks are omnipresent. Ciarán Galway meets with Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) Director Annette Connolly to discuss Ireland’s economic and fiscal landscape in 2020.

Having been based on assumption of a ‘disorderly Brexit’, to what extent is Budget 2020 prudent?

In Budget 2019 the central assumption was that there would be an ‘orderly Brexit’. At the time, the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) emphasised that this assumption was not prudent. Therefore, the PBO welcomed the decision to base Budget 2020 on the assumption of a no-deal Brexit. This was the right approach given the significant impact that a no-deal Brexit would have on the public finances.

Now that the risk of Brexit has subsided, for 2020 at least, tax revenue is forecast to grow faster (7.1 per cent) than voted expenditure (4.5 per cent) which will lead to a surplus of 0.7 per cent in 2020. However, much of the improvement in the public finances has been due to volatile corporation tax receipts and lower than expected interest payments on the government debt. These corporation tax receipts are now being used to fund current spending. This is a risk, particularly given that there are many other external risks that could hurt the economy and public finances.

Has Budget 2020 fully considered high external uncertainty/key macroeconomic risks?

Budget 2020 was set in a context of a strong performing economy but with growing macroeconomic and fiscal risks, particularly in relation to the possibility of a ‘disorderly’ or no trade deal Brexit, a slowdown in the global economy and a changing international tax environment.

Additional funding was made available for Brexit to provide support to the economy in case of more severe economic impacts. While there are issues in respect of public spending control, the overall fiscal stance was consistent with growth in underling economic fundamentals.

However, the PBO highlights that risks remain such as the reliance on multinationals and the transition to a low carbon economy. Sound public finances and a robust and dynamic economic model are crucial to address the impact of external risks, most of which are beyond domestic control.

In the current context of concentrated economic activity around multinationals, why is it important to protect capital investment now and in the future?

This concentration of activity is a key systemic risk. The PBO is concerned that Ireland is over-reliant on the economic activity of multinational corporations and the revenue generated by multinationals for the Exchequer. Multinationals account for 77 per cent of all Corporation Tax revenue, and their employees contribute a quarter of all Income tax and USC revenue.

Should downside risks materialise — whether related to a global downturn, or international tax reform — and negatively impact on the performance of the multinational sector, a sizeable portion of Exchequer revenue will be under threat.

We’ve already seen a decade of underinvestment in capital, and this has contributed to capacity constraints in key sectors (particularly in construction and higher education). This suggests that there is very limited room for additional cuts to capital planning, in the context of a future macroeconomic and fiscal crisis.

If not used to fund long-term/permanent spending, how should Corporation Tax receipts be utilised? Could the Rainy Day Fund be reconsidered, in terms of its coherence with countercyclical fiscal policy?

The Rainy Day Fund was established on a statutory basis in October 2019. Unexpected revenues, including windfall Corporation Tax revenue, should be considered for allocation to this Fund. This would prevent this revenue from being used to fund permanent spending.

Alternatively, unexpected or volatile revenues might be used to pay-down our National Debt, which is expected to be 93 per cent of GNI* in 2020, or to fund investment in one-off capital projects.

As currently designed, the Rainy Day Fund is subject to an overall cap of €8 billion. As a small and highly globalised economy, it is unlikely that this would allow for a sufficient stimulus in the event of a future macroeconomic and fiscal crisis.

As we have seen since 2015, Corporation Tax has persistently outperformed expectations by approximately €2.3 billion in 2015, rising to €4.2 billion in 2018, according to our estimates. The design of the Rainy Day Fund should facilitate the transfer of revenue windfalls of this magnitude, as and when they arise.

A further issue relates to the timing of transfers to the Fund. Payments are made to the Fund at the end of the financial year — increasing the risk that any surplus receipts received within-year will be spent, to meet budgetary overspends for instance, by the time an allocation could be made.

What concerns does the PBO have in relation to the persistent trend of supplementary estimates in respect of certain votes?

First the PBO has concerns in relation to the persistent use of supplementary estimates in general. The regular use of these estimates does not suggest that budgetary management of Votes is improving and it reduces transparency. Using supplementary estimates regularly means that the spending plans presented at Budget time are , only part of the actual spending that will happen during the year.

There is also a difficulty in measuring what improvements, if any, in public services are being delivered by Supplementary Estimates. When this additional money is sought from the Dáil in November/December, no changes are made to performance metrics that were presented to the Dáil and its committees earlier that year for scrutiny and approval.

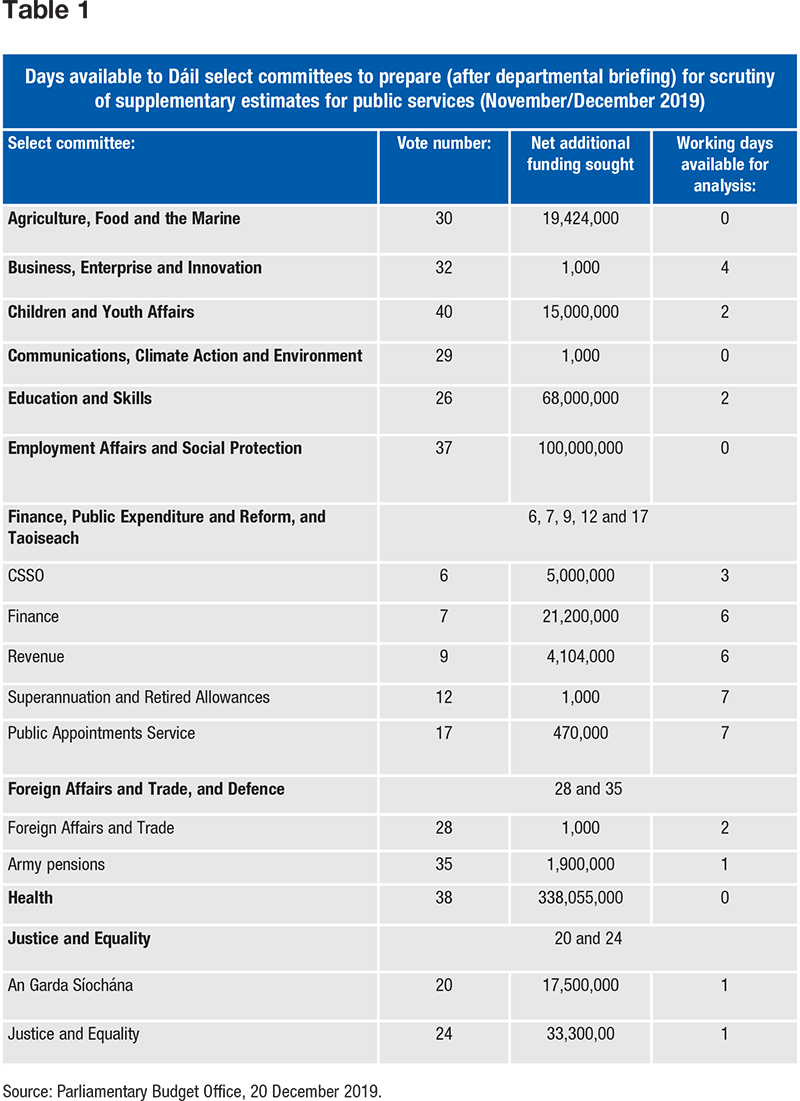

The PBO has also illustrated in one of its recent infographics how little time is provided to committees to scrutinise the extra money being sought [see Table 1]. For €7 of every €10 of additional spending requested in 2019, there were no full working days for members to analyse the briefings provided by departments.

Secondly, certain Votes such as health, education and justice regularly have recourse to Supplementary Estimates and the quantum of money involved is of budgetary significance. Seeking this money at the end of the year rather than ‘upfront’ obscures what the actual anticipated increase in spending will be in the coming year. This further reduces the usefulness of the performance metrics provided to Dáil committees during their Vote-by-Vote scrutiny following the Budget.

Should downside risks materialise — whether related to a global downturn, or international tax reform — and negatively impact on the performance of the multinational sector, a sizeable portion of Exchequer revenue will be under threat.

Is the Fiscal Monitor an effective tool for monitoring in-year spending?

As set out in its analysis of the Supplementary Estimates for Public Services 2019, the PBO relies on the data contained in the Department of Finance’s monthly Fiscal Monitor for our regular Gross Expenditure Monitor publication which aims to keep members and committees apprised of spending patterns as they develop.

Accordingly, PBO had concerns that when requests for Supplementary Estimates totalling €0.6 billion were being scrutinised by the Dáil select committees, the November 2019 Monitor was showing that net spending was €0.7 billion below what was profiled to be spent.

The PBO has also previously pointed out that the data in the Fiscal Monitor is only provided at Vote Group level and that in some cases this may obscure what is happening at Vote level.

How do we avoid a situation where Exchequer funds are directed towards programmes which have little-to-no evidence of effectiveness in achieving policy goals?

It is important to distinguish between the role of government and the role of parliament. Ultimately, government is responsible for proposing how money is to be spent and by implication ensuring that it is spent effectively and efficiently.

However, parliament does have a crucial role in the ex ante scrutiny of government spending plans through Budget debate and legislative scrutiny, Dáil committee scrutiny of the Estimates for public services, value for money and policy reviews.

Parliament also has a vital role to play in the ex post evaluation of spending particularly through the Dáil Committee of Public Accounts. The PBO recognises that government has introduced mechanisms which would assist in addressing this issue, for example the Spending Review process, and the establishment of the Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES).

Why is there a question of accuracy in relation to the forecasting models used to determine the Exchequer balance?

By their nature, forecasts are imprecise. They are estimates and will never be 100 per cent accurate. However, we have seen sizeable forecast errors in recent years, particularly for some of the more volatile tax heads. The most prominent example is Corporation Tax, which has continued to outperform expectations since 2015. Other examples include capital taxes – Capital Gains and Capital Acquisitions Tax.

The report of the Tax Forecasting Methodological Review Group was just published in December 2019 and is the third of its kind. It finds the overall forecasting performance of the Department of Finance to be robust. While this report is to be welcomed, we would recommend an annual publication by the Department, examining the performance of tax forecasts over the preceding year.

This analysis might further explore the source of any forecast errors, for example, by identifying issues relating to the macroeconomic variable that is used to predict revenues, or the inaccurate costing of policy changes. This would facilitate a more informed scrutiny of revenue forecasts.

What challenges has the PBO encountered as it continues to embed itself in the budgetary landscape?

The PBO remains a relatively recent addition to the budgetary scrutiny landscaped having been set up only in the second half of 2017. In addition, it was established on a statutory basis just over one year ago.

The PBO is therefore continuing to develop its relationship with other key stakeholders in the wider environment such as the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC), with whom we are jointly hosting the 12th annual meeting of the OECD network of parliamentary budget officials and independent fiscal institutions at Easter 2020.

Our key internal stakeholders of course are the members of the Houses of the Oireachtas. The PBO was established well after the formation of the 32nd Dáil and that carried its own challenges – we look forward to engaging with new TDs at the formation of the 33rd Dáil.

We are also continuing to develop how we access data from government bodies and this remains a complex and demanding but crucial area for development.

How has the PBO evolved in the last year in terms of internal structure?

The structure of the PBO is reviewed on an ongoing basis to ensure that it can meet the challenge of the high standards expected of an independent fiscal institution and with a view to effectively supporting the 33rd Dáil. One important milestone in the PBO’s evolution was the November 2019 launch of its policy costing service for members. This is an example of delivery on the PBO’s ambitious objective of improving the level of budgetary scrutiny.