Boom to bail-out

For a small peripheral island nation, the economy has always been high on the political agenda. Since the unfolding of the financial crisis in 2008 it has dominated Irish politics and the media. Owen McQuade looks at

For a small peripheral island nation, the economy has always been high on the political agenda. Since the unfolding of the financial crisis in 2008 it has dominated Irish politics and the media. Owen McQuade looks at

the current state of the economy and how we got to where we are.

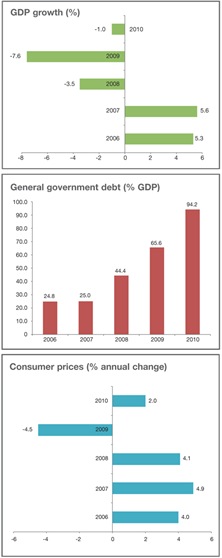

Before the bust there was a long and sustained boom over a decade starting in the mid-1990s. Unprecedented economic growth in this period saw the Irish real GDP double in size in just over a decade. Then, in the second half of 2007, the pace of growth decelerated and in 2008 output fell for the first time since 1983. The slowdown was triggered by a contraction in housing construction.

House prices had increased substantially in the late 1990s and in the first half of the last decade, investment in housing as a percentage of GNP rose from around 6 per cent in 1996 to almost 15 per cent in 2006. The slowdown in housing building acted as a significant drag on the growth of the economy. The turbulence in the international financial markets in 2007 added to the slowdown. The global downturn, with recession in the economies of our trading partners further worsened the situation.

Public finances

Once a strong point of the Irish economy, the current downturn has seen a marked deterioration in public finances. In 2006, there was a surplus of 3 per cent of GDP but by the end of 2010 this has translated into an overall deficit of around 31 per cent of GDP; this includes the cost of the bank bail-out monies and the underlying deficit is 11.5 per cent. Taxation policy over the past decade had led to a structural rise in the importance of capital taxes as a source of revenue and the slowdown in the property sector led to a slump in tax revenues.

Consumer spending and prices

The real challenge for the economy going forward is the robustness of consumer spending. With the tightening personal taxation measures, household budgets will remain under pressure. Higher prices for food, energy and insurance have also added to the squeeze on disposable incomes. VAT rose from 21 to 21.5 per cent in December 2008, before returning to the previous level in January 2010. With the economic uncertainty in the wake of the EU-IMF bail-out, consumer confident will remain fragile for 2011.

The remarkable growth seen throughout the late 1990s and into the first half of the next decade was a strong driver of employment growth. The total number of people in employment rose from 1.2 million in 1990 to 2.1 million in 2007. The rate of unemployment during this period drooped to historically low levels and there was a reversal in the trend of emigration that was seen throughout the 1980s. The current downturn cancelled out that progress on the labour market with the construction sector being hit particularly hard. That sector has now lost over 140,000 jobs, which is over half of its employment at the peak. Manufacturing and financial services also lost jobs but the international sector fared relatively well during the global crisis and has return to growth.

In March this year, the unemployment rate was revised sharply upwards in figures released by the Central Statistics Office (CSO). In the final quarter of 2010 the seasonally adjusted rate of unemployment was 14.7 per cent. This represented a 17-year high the number of people out of work.

Unemployment (annual average rate)

2006: 4.4

2007: 4.5

2008: 6.3

2009: 11.8

2010: 13.4

Export for growth

Strong growth in exports looks like being the only source of economic growth and with reasonably weak imports, due to decreased consumer demand, net trade will make a strong contribution to GDP. Although that assumes a growing world economy, particularly those economies that Ireland exports to. Irish exports grew by 6.7 per cent in 2010 to reach €161 billion, the highest ever recorded.

EU-IMF loan agreement

Although much of the attention has been on the headline interest rates within EU-IMF loan package, the conditions for the package set out a timetable for a number of key reforms. These include: fiscal consolidation, banking sector restructuring and structural reform. The new government will have some scope to negotiate and shape the details of the reform plan to suit its own policies, as long as it meets the fiscal targets.

In the new Programme for Government, the overall aim is to “secure a Programme of Support and solution to the banking crisis that is perceived as more affordable by both the Irish public and international markets.” The programme outlines a number of key strategies that will be pursued by the coalition and these include:

• seeking a reduced interest rate for the loan package;

• deferring recapitalisation of the banks until solvency stress test are known;

• ending further asset transfers to NAMA;

• ensuring an adequate pool of credit is available for SME;

• restructuring of bank boards and replacement of directors who presided over bank failures;

• establishing a strategic investment bank.

2011 Jobs Programme

The rise in unemployment as a result of the financial crisis featured highly the election campaign. The new Government has included a 2011 Jobs Programme in the Programme for Government, with the resourcing of a ‘jobs fund’ within the first 100 days of the new administration. This programme will provide resources for an additional 15,000 places in training, work experience and education for those who are out of work.

IBEC Director-General Danny McCoy welcomed the commitment but said a “concerted effort towards cutting business costs is now vital if the positive performance of the export sector is to be matched by a domestic recovery.”

Reflecting on the last Government, ICTU General Secretary David Begg said the “cumulative effect” of its light regulation policies “was to entirely erode the country’s tax base and inflate the boom”.