Care home reform: The key policy questions

Since moving on from its nadir in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Ireland’s elderly care sector still faces significant challenges, specifically in relation to nursing homes infrastructure which has been cause for concern long before the coronavirus pandemic brought it to renewed nationwide attention.

A briefing note sent by Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) chair Pat O’Mahoney to Minister for Health Simon Harris TD in February 2019 warned of the pressing challenges now facing the care home sector. O’Mahoney wrote of “ongoing challenges in relation to the physical premises of some centres”.

The briefing detailed to the Minister prevailing conditions within care centres in Ireland which mean that older people “experience care that is institutional in its approach and follows a medical rather than a social model of care”. Such an experience is antithetical to the stated aims of health care in Ireland in the Sláintecare era. The note also explained how people in centres are living with “little privacy and dignity” due to being in multioccupancy rooms and that “the needs of the service dictate when they can get out of bed and when they can eat a meal”.

It is also said that life inside of the centres has, for some, been defined by “living in fear of other residents due to peer-on-peer altercations, higher levels of restrictive practices and limited support to live as independently as possible”.

There has been an increase in the number of immediate or urgent judgements handed down to these centres by HIQA since 2015, with 15 being issued in 2016 and 29 in 2018 as the total number of inspections also increased. One-fifth of the 582 total centres in Ireland currently operate with some additional requirements attached to their registrations, typically refractions that require addressing and correction rather than being serious enough to warrant closure.

Overall, the number of seriously non-compliant centres has been on the wane, with O’Mahoney’s note telling Harris that there were seven centres that “owing to such poor regulatory compliance, the chief inspector is not in a position to renew their registration”. HIQA’s last report on the quality of care in nursing homes, published in 2019 and surveying the year 2018, found that 123 of the 444 homes inspected that year were fully compliant with regulations.

This represents a marked changed from the 2000s, when RTÉ’s exposure of institutional abuse occurring at the Leas Cross home in Dublin led to a HSE report into the nursing home sector that found that “the context within which this occurred was that of policy, legislation and regulations”.

Arising from the scandal, the Government founded HIQA and between 2009 and 2012, the authority closed 14 homes, with a further 18 voluntarily shuttering, most in the face of either extreme scrutiny or the financial pressures of complying with new regulations. Since then, HIQA’s model has changed to that of a co-operation model between facilities and the regulator. While they retain the power to shut down homes if such action is judged to be necessary, the authority now seeks to work with facilities in order to improve standards across the board.

In 2016, a five-year grace period was introduced for non-compliant homes to come up to the standards originally laid down in 2007. After this grace period, the homes will be legally obliged to meet the improvement targets set down to them by HIQA, but O’Mahoney’s briefing of Harris that by February 2019, it was “becoming apparent that that agreed plans for particular centres are either not happening at all or are not advancing at the required pace”. Aside from the seven centres already failing to meet standards, a further 45 were told that they would not meet the 2021 deadline, leaving the sector facing future censure especially with regard to HSE managed facilities. “In the main, our problem with environmental compliance is with the HSE,” HIQA chief executive Phelim Quinn told the Irish Times last year.

“Aside from the seven centres already failing to meet standards, a further 45 were told that they would not meet the 2021 deadline, leaving the sector facing future censure especially with regard to HSE managed facilities.”

The legislative constraints and policy challenges that have hamstrung meaningful reform in the sector were the focus of an Oireachtas Spotlight report in January 2018. Home Care for Older People: Seven Policy Challenges honed in on the seven most pressing issues with regard to delivering the kind of legislative change that HIQA has been pushing for. They are:

1. Determining eligibility and entitlement

There is currently no statutory entitlement to publicly funded home care, a position that the report says causes “a lack of clarity and consistency about who is eligible for services, and how services are allocated”.

2. Selecting a funding model

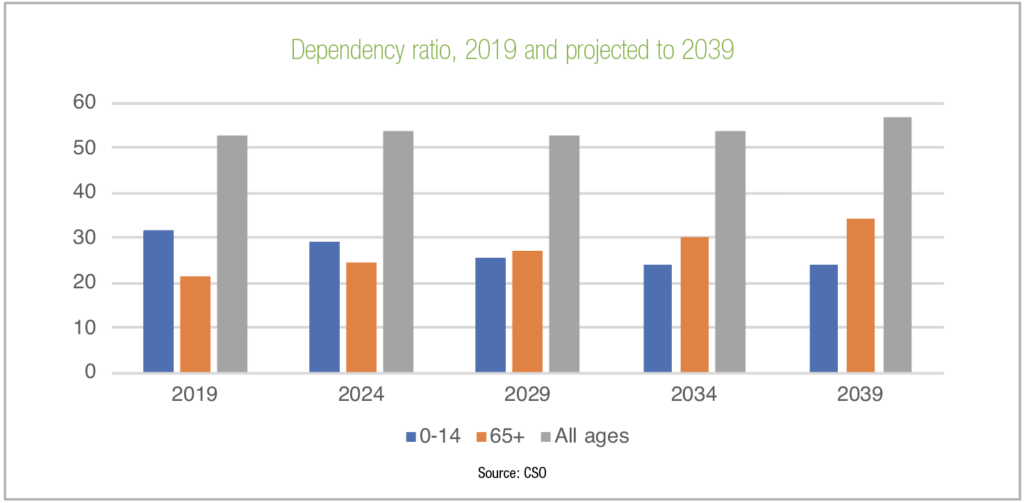

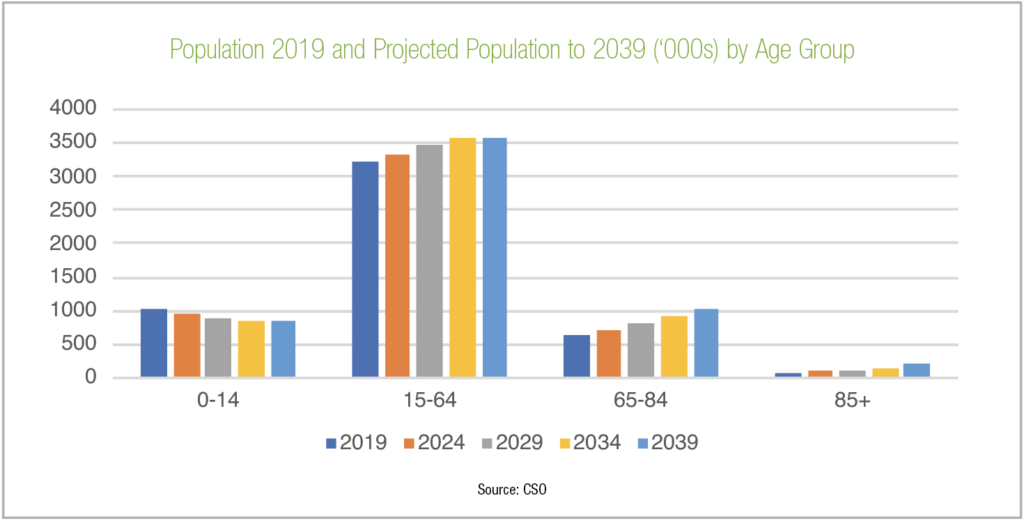

Publicly funded home care currently operates on a supply-led basis, which will come under pressure with demand forecast to increase. Options the report proposes for the increased funding that will be necessary include “general taxation, care insurance, and applying a similar model to the Nursing Home Support Scheme (NHSS)”.

3. Finding the right mix in service provision

Determining what portion of home care should be delivered by public, private and voluntary sectors.

4. Introducing effective regulation

There is currently no regulatory regime for home care and no external regulation for private homes. The report calls for a regulatory system that “balances successfully the benefits of regulation (such as improved quality) against costs (e.g. a potential loss of choice, and direct and indirect financial costs to the State (taxpayers), industry and individuals as users of services)”.

5. Sustaining informal care

“A combination of employment supports, income supports, and health and social care supports is likely to be considered” in order to support those who make up the bulk of at-home carers in Ireland, unpaid family and friends.

6. Securing a care workforce

Given the challenges involved with the recruitment and retention of care staff, the report suggests that moving “all care into the formal labour market is likely to be a consideration”. This does come with the caveat however that “tensions may arise between the rights and claims of workers and the demand for affordable care”.

7. Developing alternatives to nursing home care

A key component of modern health care strategies including Sláintecare, the “policy challenge here is to develop stronger services and supports across a spectrum (such as sheltered/supported housing and reablement interventions)”. One stumbling block here could be the need to bridge typically disparate professional and sectoral boundaries.

With the grace period in which homes were to bring their facilities up to standard now severely disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic which simultaneously exposes the total unsuitability of multioccupancy rooms, given the alarmingly high death rates within homes. The sector now stands at a crossroads.

The Spotlight report of 2018 concluded: “With the development of a statutory scheme on the horizon, policymakers must consider the significant challenges presenting in this dynamic sector – such as decisions about who should care, what type of supports are required, the oversight of care quality and how to secure the funding of care into the future – many of which raise key ideological questions.”

Over two years later, those questions have acquired even greater significance.