Climate and the built environment

The ambition to tackle climate change requires radical action across all spheres including the current and future built environment. Delivering the necessary infrastructure for carbon mitigation will require a large input from the construction industry.

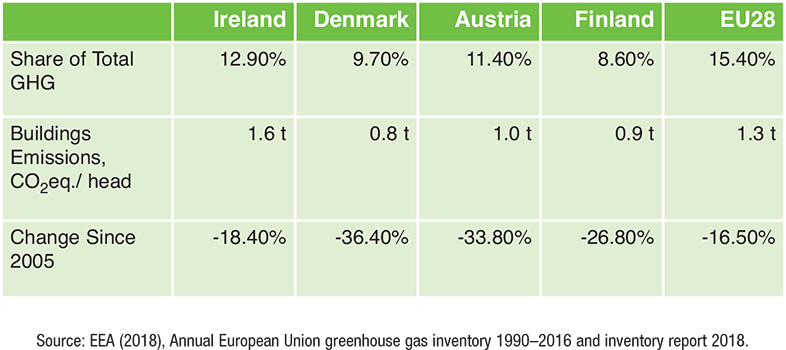

The built environment accounted for almost 13 per cent of Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2017 and has been identified as an area in need of intervention if Ireland is to meet its revised 2030 climate targets.

Ireland has failed to meet its original 2020 target in relation to greenhouse gas emissions but in acknowledging this failure has delivered a roadmap of ambitious change over the next decade which the Government hopes will align Ireland closer with those EU member states leading on climate change mitigation.

Ireland has made significant reductions in building decarbonisation since 2005 of almost 2Mt CO2eq, however, this still compares poorly to European member states leading in this area. Ireland’s buildings emissions CO2eq per head is 1.6 tonnes, above the 1.3 tonnes EU28 average and significantly above exemplars such as Denmark (0.8 tonnes) and Finland (0.9 tonnes).

Ireland faces significant challenges in catching up with these members states and the EU average. Homes in Ireland use 7 per cent more energy than the EU average and emit almost 60 per cent more CO2eq. A major factor in this is a heavy reliance on fossil fuels, with 70 per cent of buildings fossil fuel reliant. At the same time, the vast majority of houses and businesses have poor energy efficiency, with over 80 per cent being graded C or below for their Basic Energy Rating (BER).

The significance of the need to address the built environment if Ireland is to effectively manage its overall greenhouse gas emission reduction can be highlighted by the fact that in 2018 a colder winter meant an almost 8 per cent rise in household emissions.

The Climate Action Plan launched in June 2019 recognised a need to go beyond ambitions set out in the broad Project Ireland 2040 and effectively double the annual rate of emission reduction from 2 per cent to almost 4 per cent.

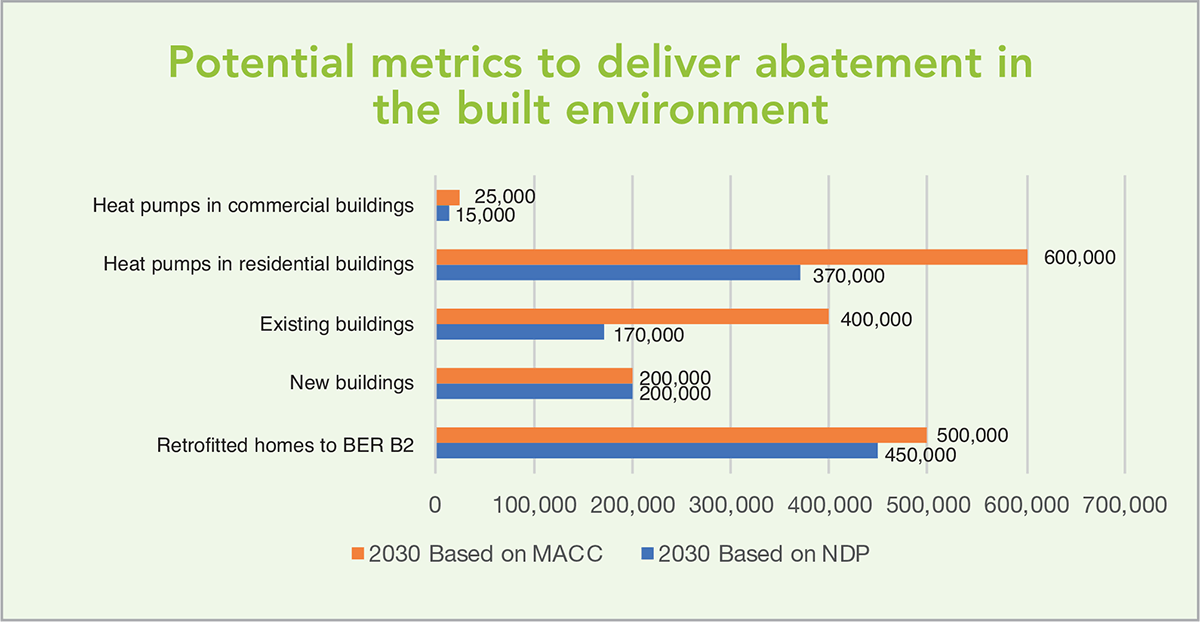

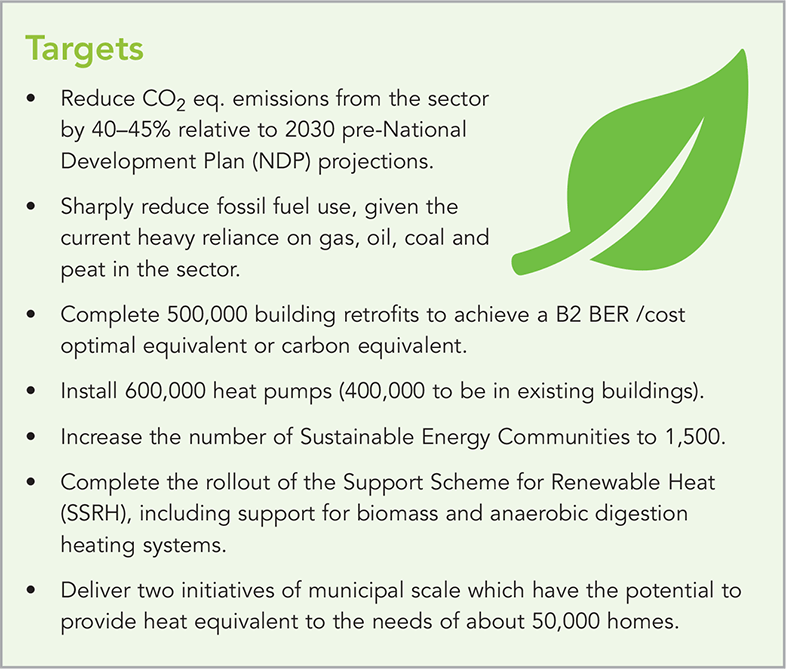

The Plan sets out to reduce built environment sector emissions to 5 Mt CO2eq by 2030 and recognises that the most cost-effective measure is for a retrofit of existing oil boiler using dwellings to a B2 equivalent BER. Transitioning these dwellings to gas is accepted as potentially prohibitive for potential future carbon reduction ambitions and so, the Plan states that “we must ensure the introduction of heat pumps and other low-carbon solutions in new residential and commercial buildings”. Targets by 2030 included in the Plan are seen in the graphic.

Retrofitting

In August 2019, the Environment Minister Richard Bruton TD announced the establishment of a retrofitting model taskforce to take forward plans to retrofit 500,000 homes. A new delivery model for retrofitting is necessary after the Government’s controversial deep retrofit pilot scheme. The Government U-turned on the decision to suddenly end the deep retrofit grant scheme, allowing householders who had already spent money in preparing their homes for more complex grant-aided works and applied before the deadline to be included.

A lack of funding was blamed on the Government’s decision to close the scheme, which it said received a “huge level of interest”. As a result, the Climate Action Plan has now indicated a move from individual and small scale initiatives to “a much more scaled-up model”.

Delivering a scaled-up model will require capacity in the construction sector at a time when various pieces of large infrastructure will all be vying for skills and resources. The Plan suggests that the retrofit taskforce will “examine grouping large numbers of houses together to achieve economies of scale, leveraging smart finance, and ensuring easy pay-back methods”.

Other significant ambitions include: an upgrade of local authority housing stock under Phase 2 of the social housing retrofit programme to bring dwellings more than 40 years old (30 per cent of the social housing stock) to a B2 equivalent BER; an ongoing deep energy retrofit programme for pre-2008 schools; anda new public sector decarbonisation strategy building on the Public Sector Energy Efficiency Programme ambition to support public bodies to achieve 50 per cent energy efficiency for 2030.

Building and renovation regulation

A major initiative in future-proofing the ambitions for emissions in the built environment is the change to building regulations on energy efficiency, making them more stringent. Effective from the 1 November 2019 (subject to transitional arrangements), new regulations aim to make all new residential dwellings 70 per cent more energy efficient than 2005 performance requirements.

Signed into law were Part L of the Building Regulations, giving effect to Nearly Zero Energy Building (NZEB) Regulations and Major Renovation Regulations and amendments to Part F of the Building Regulations, which relate to ventilation.

The regulations transpose Articles 7 and 9 of the EU’s 2010 Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Recast) into Irish law and require all new homes to be NZEB by 31 December 2020. The new regulations will require that 20 per cent of the total energy use of buildings is sourced from renewables.

Also, the Directive requires that where major renovations (defined as a renovation where more than 25 per cent of the surface envelope of the building undergoes renovation) are carried out on a building, the whole building or dwelling should achieve a cost optimal energy performance insofar as it is technically, functionally and economically feasible.

Crucial to the extent to which new builds and renovations will have an effect on carbon emissions will be the levels to which they are undertaken. Undoubtedly, new regulation will mean an increase in costs, at least in the short term. Additional costs could be a source of delay in terms of large company investment decisions or individuals deciding on renovation. To this end, the Climate Action Plan has recognised the need for smarter considerations around finance. The Plan pledges to develop a “smart finance initiative” providing a competitive funding offer with State support. It also floats the idea of ‘easy pay’ salary incentive schemes and ‘green mortgage’ opportunities.

District heating

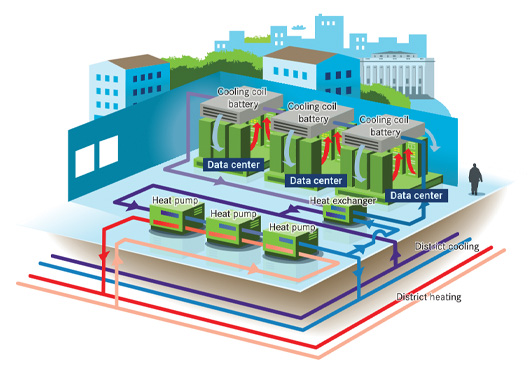

In December 2019, the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment launched a public consultation aimed at informing a policy framework for the development of district heating in Ireland.

Ireland has one of the lowest (less than 1 per cent) shares of district heating in Europe and it is recognised that district heating represents a relatively low resistance path to decarbonisation without relying on large volumes of individual heat consumer decisions. The Government has pledged to ensure the potential of district heating is considered in all new developments and in particular in Strategic Development Zones (SDZs) and identify a set of potential early mover projects.

Two pilot district heating schemes are being developed in Dublin. Tallaght District Heating Scheme will provide heat and cooling to a 1,200-apartment development, Tallaght IT and South Dublin County Council buildings and is the first project in Europe to source heat from a local data centre. The Dublin District Heating Scheme will link to Covanta’s waste-to-energy plant in Ringsend and serve Poolbeg, Grand Canal Dock and North Lotts strategic development zones.

Also included in the plan is the recognition that more needs to be done to ensure the construction industry is equipped to deliver on the ambitions set out over the next decade and beyond to 2050. The Climate Action Plan outlines a need to skill-up current contractors and other industry stakeholders in deep retrofit, NZEB and new technology installations, as well as developing the supply chain for renewables and retrofitting through engagement with education and training boards and SOLAS, which manages a range of further education and training programmes.

Energiesprong

The Climate Action Plan presented a case study of the potential approach for ambitions for a scaled up retrofit scheme. The Energiesprong programme rolled out by the Netherlands government has been mimicked in the UK, Italy, France and Germany. The scheme aggregated demand for retrofits before deploying builders to complete the work at pace. Builders were incentivised to improve efficiency and speed, and got the turnaround time to retrofit a house down to three days. The initiative used social housing as a launch pad before rolling out the approach across the private sector, and was financed by housing companies, which achieved savings on energy costs, repairs and maintenance.