Climate change: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability

“The science is clear, any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future,” explains Hans Pörtner, co-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II.

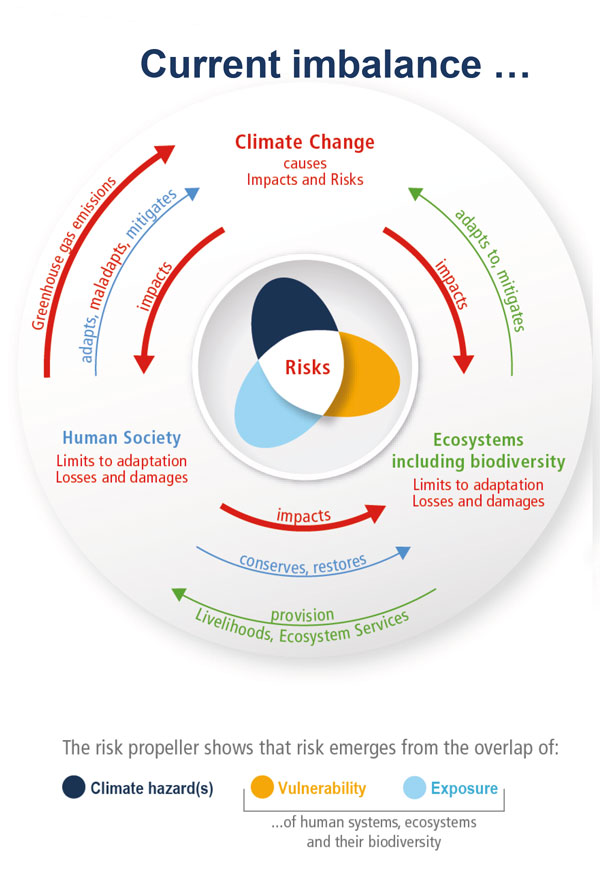

Pörtner outlines the key findings of the Climate Change 2022 report, the working group’s contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, which not only assesses the impacts of climate change by looking at ecosystems, biodiversity, and human communities at global and regional level, but also reviews the vulnerabilities, capacities, and limits of the natural world and human societies to adapt to climate change.

Setting the context for the report, Pörtner says that it is clear human pressure on biodiversity is increasing constantly, with conservation efforts failing to stem the loss of biodiversity on a global scale. In parallel, man-made climate change is increasingly threatening nature and its contributions to people, leading to losses to overfished stocks, excessive droughts and wildfires, and heatwaves.

“The scientific evidence is clear, climate change is a threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet,” he states. “We need to consider how resilient we are with respect to the changes that are ongoing. Between 3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in hotspots of high vulnerability across the continents, including large parts of Africa, South Africa, Central and South America, small islands, and the Arctic.”

Pörtner explains that a larger concern is that not only are these places of high vulnerability, but also where the largest changes are occurring with respect to destruction of natural resources and the life-sustaining functionality of ecosystems. This, in turn, impacts the areas where the human species can exist. Exposure to high temperatures and high humidity will have consequences for migration movements, with wider impacts such as economic disruption.

“Our civilisation, our current system that we look at as being the backbone of our wellbeing and of our wealth, is clearly in danger under climate change,” he adds.

Pörtner highlights that risk is not just isolated to humans. A rise in global warming to 3°C, as is predicted without severe mitigation, would see a 10-fold increase in extinction in biodiversity hotspots, a backbone for the life-saving functions of ecosystems and their productivity.

“Nature’s crucial services are at risk in a warming world,” he states. “Climate change combined with unsustainable use of natural resources, habitat destruction, growing urbanisation, and inequity. Very clearly, on all continents, this is reducing people’s and nature’s capacity to adapt.”

Highlighting that warming alone is not the sole driver and that simultaneous extreme events and impacts compound risks, the co-chair offers the example of the knock on effects of increasing heat, meaning a reduction in crop yields made worse by heat stress among farm workers. Reduced crop yields also means increased food prices and reduced household incomes. A local effect, therefore, quickly becomes a global challenge.

Another example offered by Pörtner is the impact of rising temperatures on water scarcity. At 2°C warming, regions relying on snow melt would have a 20 per cent decline in water availability for agriculture after 2050.

The IPCC uses a complex evaluation of global and regional risk, relating that risk to global warming with the aim of providing guidance on climate action through mitigation and adaptation, while also considering the limits to adaptation.

The evidence reiterates the science that risk can be kept at a moderate level more often by keeping global warming below 1.5°C. This, however, does not mean that damage will be reversed. Data on warm water corrals, for example, a largescale ecosystem service, shows that they have already passed the tipping point of exposure. At 1.5°C, 70 to 90 per cent of them will be lost but if the globe’s temperature rises to 2°C, 99 per cent will be gone.

“To avoid mounting losses, it is urgent to adapt to climate change and close the adaptation gap,” he states. “Keeping the maximum number of adaptation options open by deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.”

Adaptation

Adaptation options listed in the report include the likes of: water management; improving food security; transforming cities; the co-benefits of mitigation; and avoiding maladaptation.

However, as the co-chair explains, even effective adaptation cannot prevent all loses and damages. Pörtner explains that with warming above 1.5°C, some natural solutions may no longer work and a lack of freshwater could mean that people living on small islands and those dependent on glaciers and snowmelt can no longer adapt. A rise to 2°C will be challenging to multiple farm staple crops in many current growing areas.

Setting out that ambitious emissions reductions protect biodiversity and its contributions to climate mitigation and the bioeconomy, Pörtner highlights the global challenges that need mastering, including the avoidance of deforestation and degradation of intact ecosystems; a reduction of land use competition, which can affect food prices and impact food security and livelihoods with possible knock-on effects related to civil unrest; a reduction of excessive land use for animal feed production; the development of novel food and feed sources; and the implementation of broad education initiatives.

Spatial planning

Pörtner stresses that spatial planning is key to integrating conservation, climate and societal actions.

“Treating climate, biodiversity, and human society as coupled systems is key to successful outcomes. To be successful, conservation and climate actions would go hand-in-hand across landscapes, in cities and rural areas, taking people’s needs into consideration, for maximised benefits for climate, biodiversity and humans.”

The solutions framework included within the report, aimed at delivering “climate resilient development”, has ecosystem stewardship at its core and seeks to deliver effective and equitable conservation and restoration of approximately 30 to 50 per cent of land, freshwater and ocean ecosystems can help ensure a healthy planet.

Pörtner concludes: “Starting today, every action, every choice and every decision matters. Worldwide action is more urgent than previously assessed. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future.”