Comparing Covid-19 on the island of Ireland: Impossible, undesirable or doable?

There are two significant obstacles to a comprehensive understanding of the impact of Covid-19 on mortality in Ireland. One is the statistical challenge while the other is an unwillingness to pursue comparative study on a north/south basis. Mike Tomlinson, Emeritus Professor of Social Policy, Queen’s University Belfast, writes.

As the first wave of Covid-19 subsides, I suspect we have lost our appetite for numbers. There is something morally questionable about reducing so many lives cut short to an overall death toll or a death rate, especially when this comes across as an unseemly international league table. Exactly the same sentiment arises over north/south comparisons on the island of Ireland. The North’s Minister of Health recently described such comparisons as ‘crude and often ghoulish’. But compare we must, as this is the way we learn from others.

Over a month ago (22 April 2020), The Irish Times published an opinion piece in which I suggested that the Covid-19 death rate in the North was considerably higher than in the Republic: ‘One island with two very different death rates’ ran the headline. Different policies – on the pace of lockdown and on testing and tracing – appeared to have resulted in different outcomes.

Reaction

The response to this was not what I expected. It ranged from the First Minister’s special adviser referring to the piece publicly as “the now widely dismissed report”, to the London-based think-tank Policy Exchange devoting a 15-page pamphlet to the topic. More surprisingly, two days after publication Facebook branded the Irish Times piece as ‘partly false’. This ensured that the article was relegated in the news feed, and distribution reduced. People sharing the content were referred to a report by a third-party fact-checker which had rated the statistical comparison as ‘unsubstantiated’. The false news tag remained in place for a full week until Facebook reclassified the piece as ‘opinion’ on 01 May 2020.

Reactions to north/south Covid-19 comparisons fall into two broad camps. First there are those who suggest that it is impossible to compare Northern Ireland with the Republic as the published statistics count different things. Then there are those who say that north/south comparisons are undesirable, although typically this is implied rather than stated outright.

It is certainly difficult to compare the data on deaths. For the Republic, the reported deaths include those tested positive for the disease and ‘probable’ Covid-19 deaths referred to the Coroner. No other data will be available until the mortality statistics for the first quarter of 2020 are published later this year, probably in August.

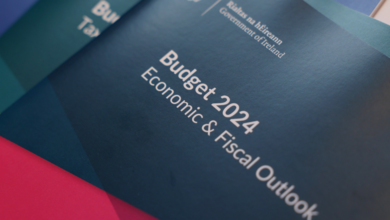

For the North there are four figures to choose from. The lowest of the four is the daily reported number of Covid-19 deaths based on those tested positive for the disease and published by the Department of Health. Then there are three statistics published weekly by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). Two of these are a count of death certificates which mention Covid-19: by date registered and by date of occurrence. Finally, we have a figure for ‘excess deaths’, a measure of the spike in deaths over and above what would normally be expected at this time of year, based on an average for the preceding five years. This is the highest figure.

Three of these four counts are shown in the graph (Figure 1) below (I am indebted to Chris Giles economics editor at the Financial Times for the design of this graph). The top set of columns represent an estimate of the excess deaths occurring between the weekly published figure.

Comparison

Where does this leave us for making comparisons? At the time of writing, the daily reported figures indicate a death rate for the Republic of 31.9 per 100,000 population and 26.3 for the North. How is it that the North, with later lockdowns and more restrictive testing, is recording a lower crude death rate? This is contrary to what one might expect from the international experience where countries following World Health Organisation guidelines and acting quickly, have recorded much lower Covid-19 death tolls.

The daily counts receive the most publicity and are the most often quoted. But they are not comparable for two reasons. First the Republic’s daily total includes deaths that have not been tested positive for Covid-19. Secondly the North’s daily figure consists mostly of hospital deaths whereas these are only a minority (about 40 per cent) in the Republic’s daily total. This is a direct result of different testing policies. In the Republic, testing and contact tracing, whatever the difficulties, were expanded from early March. But from 12 March, the British Government decided to stop contact tracing and to restrict testing to hospital patients.

Within a matter of days, the North fell behind the Republic in the confirmation of cases. By 21 March, the Republic’s case rate was double the North’s and the recent expansion of testing in the North has not as yet changed the overall picture: the Republic’s rate at 494 per 100,000 population (20 May) remains more than double that in the North where it is 235 per 100,000 population. Put another way, about one in 50 have been tested in the North compared to one in 20 in the Republic.

Excess deaths

One way of approaching the comparison is to go for the highest number in Figure 1: excess deaths. This is regarded as the gold standard for assessing the impact of an epidemic or other exceptional event on mortality. As distinguished statistician David Spiegelhalter says, excess mortality “is currently a reasonable measure of the total impact of the epidemic, both the virus and the measures taken against it”.

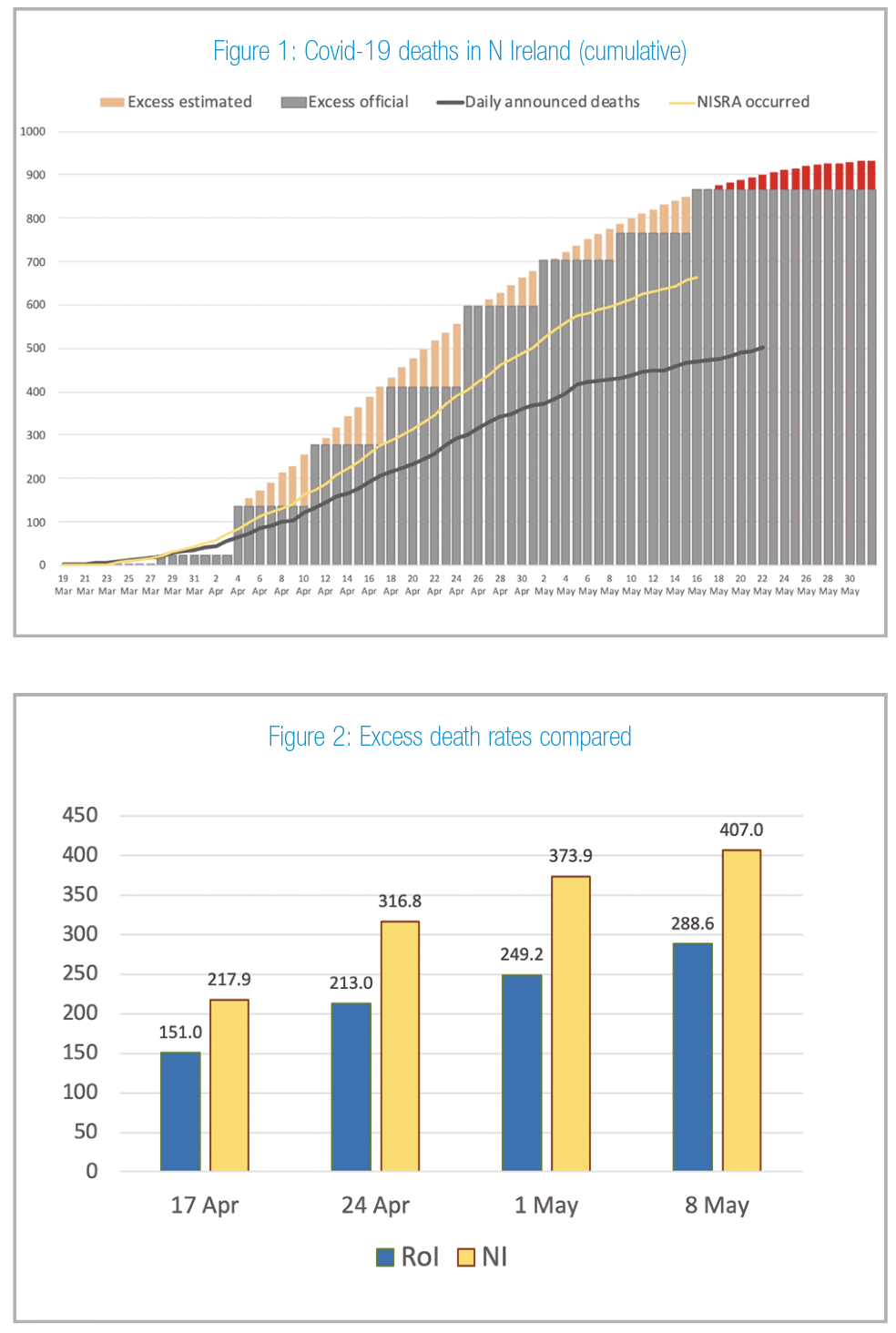

What about excess deaths in the Republic? While weekly mortality statistics are not published, there is a proxy for excess deaths that several academics are now using to assess the impact of Covid-19. Seamus Coffey, University College Cork, has shown that there is a remarkably close relationship between the official count of registered deaths and death notices posted on RIP.ie going back over a number of years.

This means we can compare north/south excess deaths using the proxy as shown in Figure 2. The graph compares excess death rates at four dates, based on cumulative totals. At every point the North’s rate is well above the Republic’s, narrowing slightly to 41 per cent higher for the latest date shown. This is a very similar result to the one provided in my Irish Times article.

As the policy discussion turns to how and when to relax lockdown measures, there is a danger that efforts to suppress the virus will be undermined if the two jurisdictions do not follow similar policies. Two areas stand out. First, testing, tracing and isolating practices need to be aligned to prevent the infection circulating more freely in the North relative to the Republic. Secondly, as Gabriel Scally and others have argued, health surveillance at points of entry to the island needs to be the same either side of the border.

Ideally in future, the Republic will shorten the time allowed for a death to be registered from three months to five days and will publish mortality statistics weekly as in the North and on a similar basis. The need to compare outcomes does not disappear with the first wave.