Competitiveness: All-island productivity gap dramatic

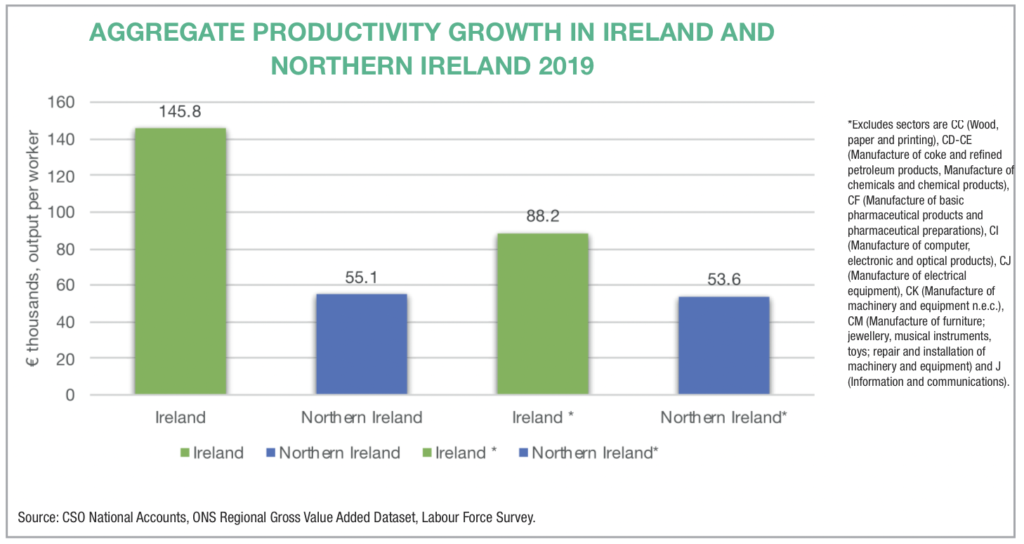

A productivity gap of some 40 per cent per worker has emerged between the Republic and the North in the past 20 years, highlighting the significance of within-sector productivity failings.

A new research report by the ESRI, examining sectoral productivity differences in Ireland, has found that despite broadly equivalent productivity levels between the two jurisdictions in 2000, over the past two decades a noticeable gap has appeared as levels in the Republic trended upwards while levels in the North have trended down.

Deemed as the first comprehensive study to compare productivity in Ireland, the ESRI study purposely excludes economic sectors with high concentrations of multinational companies which are recognised as having a distortionary impact.

That productivity in the North is comparatively poor compared to neighbouring economies has been well evidenced in recent years. However, almost all efforts to measure its productivity have focused on comparisons with other UK regions. Latest figures show the North’s productivity to be around 17 per cent below the UK average, the lowest of any UK region. This is significant in the context of the productivity growth stagnation experienced by UK economy itself over the last decade.

Productivity is crucial to an economy’s long-run performance, with higher productivity associated with higher wages, and ultimately better living standards.

Modelling productivity levels in Ireland and Northern Ireland, authored by Adele Bergin and Seamus McGuinness, exploits annual sectoral-level data on labour productivity measured by gross value added (GVA) per worker and models the determinants of productivity in each respective region.

Comparing 17 sectors, the report finds that 14 sectors in the Republic noticeably outperform their northern counterparts in productivity levels.

Particularly large gaps are highlighted in areas such as administrative and support services activities; financial and insurance activities; legal and accounting activities; and scientific research and development.

The North exhibits an advantage in just two sectors: Electricity and gas supply, and construction.

Most significant is the scale of the gap which has emerged since the year 2000, when productivity levels in the two regions were broadly equivalent. The research estimates that by 2020, productivity per worker was approximately 40 per cent higher in the Republic compared to the North.

Outlining the major factors in the Republic’s performance, the research highlights a trend between increased sectoral productivity with levels of investment and, the employment share of educated workers.

Additionally, productivity tends to be higher in sectors where there is a greater proportion of part-time workers employed, while export intensity is an important factor in driving Irish productivity.

Most notably, the report found “no evidence of a causal relationship between the range of factors captured”, despite using comparable data sources and applying the same estimation methods used for the Ireland model in areas such as education, investment and exports.

The report states: “Such an outcome raises questions regarding the underlying competitiveness of the Northern Ireland economy and its responsiveness to changes in what are generally considered key policy leavers.”

Highlighting that the models for the North do not show significant results for the usual drivers of productivity levels, the report suggests that a range of other factors including limited results from regional policy and historical reliance on public sector employment have all combined to “subdue the impact of market forces among Northern Ireland firms leading to a productivity trend that appears largely exogenous with respect to key policy variables”.

Utilising a separate modelling approach in an attempt to understand why the two economies are not functioning the same way, despite similar sectoral employment, the research finds that differences in investment and labour market-related endowments can explain almost all of why the Republic’s productivity levels were 30 per cent higher by around 2011.

Breaking that productivity gap down further, the authors suggest that the largest cause of the productivity gap relates to lower levels of investment (22.7 per cent less); and lower proportions of workers educated to post-secondary level in Northern Ireland account for a 15 per cent gap.

Simulating how productivity in the Irish economy would fare if operating with the same levels of investment and human capital currently employed by northern firms, the research outlines that the level of productivity would be around half its current productivity level.

Responding to the report, David Jordan, research fellow with the Northern Ireland Productivity Forum at Queen’s University Belfast says that the failure to translate a reduction in Northern Ireland’s ‘brain drain’ of graduates into improved productivity suggests other aspects of human capital may now be increasingly important, including workforce skills.

Additionally, he highlights the author’s conclusion that the North’s economy has failed to respond positively to increases in education, investment and export intensity, suggesting that other barriers to productivity exist.

“The report supports the view that there is no single cause of Northern Ireland’s low productivity. A greater understanding of the barriers to productivity growth is therefore needed if Northern Ireland is to emulate [the Republic’s] success,” he concludes.