De-risking renewables: the investment imperative

The IBEC-CBI Joint Business Council considers how to bridge the financial gap in renewable energy.

The IBEC-CBI Joint Business Council considers how to bridge the financial gap in renewable energy.

Economies around the globe are facing a unique investment challenge as they transition over the next few decades to low-carbon economies. Leading the charge are developed economies, whose long consumption of fossil fuels has left them at the top of emissions tables and most in need of decarbonisation. Emerging economies are following swiftly behind however, and with growth rates tipping into double figures for some, the need to find cheaper, more sustainable sources of energy is charging up the business and political agenda. With traditional, carbon-intensive energy sources such as coal and oil dwindling and with tough emission reduction targets to adhere to, the pressure is well and truly on for governments.

This will be a journey of opportunities as well as costs however, with clear advantages in the shape of new industries, new jobs and new markets for those that get their economies in shape. Respective ministers in Stormont, the Dáil and Holyrood are keenly aware of the direct and indirect benefits, and have been pushing ahead with ambitious plans to kick-start and maintain investment flows in a range of renewable energy sources, from tidal and wind to biomass and geothermal. Parliamentary committees are doing their bit too, keeping pressure up and proffering evidence-based ideas for removing barriers to success on the green energy agenda; and of course businesses have stepped up to the plate, deploying innovative new technology and committing funds even where the risks are high.

Aquamarine Power for example, began to harness the huge potential of marine hydropower by installing the world’s first near-shore hydro-electric wave power machine, the Oyster, on the seabed off the Orkney coast in Scotland in 2009. With their next-generation Oyster 800 device about to be deployed in Orkney this summer and with strong R&D links with Queen’s University in Belfast, Aquamarine Power is showing the way. The company is now backed by utility SSE and international power conglomerate ABB who can clearly see the potential of the sector. Aquamarine Power now employs over 60 people directly, and boasts a supply chain which is over 90 per cent in the UK. The goal of Chief Executive Martin McAdam is to make marine power competitive on cost with offshore wind by 2017; judging on his company’s recent performance that seems like a target that will be met.

The challenge

For every success story however there are others of frustration and failure, and the huge demand for green energy makes attracting it to the outermost northwestern corner of Europe a pressing challenge. A recent CBI report ‘Risky Business: Investing in the UK’s Low Carbon Infrastructure’, identified three key specific challenges that are hindering investment in a range of low-carbon infrastructure, including renewable energy:

• Existing funding channels are insufficient to meet the pace and scale of investment

Capital is needed now, and lots of it. However, big investors are worried that the amounts are simply too high and that major utilities operating in Northern Ireland, the Republic and Scotland simply cannot accommodate such an outlay on their balance sheets. Research from Ernst & Young suggests that project finance from the banking sector and investment from infrastructure funds will not be able to make up the difference, amounting to what Barclays and Accenture are calling a “carbon capital chasm.” The investors holding the largest pool of capital – institutional investors such as pension funds – are usually only willing to accept very low risks, which is why they have so far generally chosen not to invest directly in low-carbon energy projects.

Capital is needed now, and lots of it. However, big investors are worried that the amounts are simply too high and that major utilities operating in Northern Ireland, the Republic and Scotland simply cannot accommodate such an outlay on their balance sheets. Research from Ernst & Young suggests that project finance from the banking sector and investment from infrastructure funds will not be able to make up the difference, amounting to what Barclays and Accenture are calling a “carbon capital chasm.” The investors holding the largest pool of capital – institutional investors such as pension funds – are usually only willing to accept very low risks, which is why they have so far generally chosen not to invest directly in low-carbon energy projects.

• A shift in finance and capital conditions has created a challenging backdrop to investments

The legacy of the credit crunch has had significant implications for debt finance, the availability of which has been constrained due to reduced liquidity in the banking sector and the need for banks to repair their balance sheets. Lending activity is also likely to be constrained by increased scrutiny and tighter due diligence requirements in the financial services industry. The cost of debt has increased, with project finance fees doubling in the last two years. Lending periods have reduced to around 6-7 years, posing a particular problem for large low-carbon infrastructure projects which will have much longer timescales and will therefore need to refinance.

In addition, it seems that the financial crisis has permanently dampened the risk appetite of investors at the global level, with the CBI’s 2009 Shape of Business report suggesting that a much lower profile will be shouldered in the future, including in the equity investor market. This will have implications far and wide in the economy, but will impact particularly badly on the renewable energy sector, whose risk-profile has long concerned funders who have forayed into the tech sector without the same fears.

• Low-carbon investments are perceived as too risky

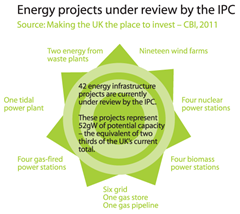

Difficult market conditions shouldn’t necessarily prevent investment; if there are returns to be made, investment will be forthcoming. However the view among investors is that low-carbon investments are faring less well than conventional investments because their returns are either not sufficiently attractive or are too uncertain. Many low-carbon technologies, even those close to commercialisation, have no track record for investors to go by, which makes them a riskier investment prospect. For example, Round 3 offshore wind will use next generation wind turbines which are larger than existing turbines and as yet untested. Add to this considerable policy risk, with planning permission a particular bête noire of the renewable industry (see exhibit above for a snapshot of projects stuck in the UK Government’s planning process). And of course the capital intensity of most low-carbon infrastructure investments means that there are long and often uncertain payback periods, leaving investors exposed during the construction phase of the project.

The solution

Importantly though, co-operation and strategic partnerships are being developed between governments and regulators across the three regions, and the work of bodies such as the IBEC- CBI Joint Business Council underpins these relationships to help deliver the end-goal of a more attractive investment environment. The Tri-Energy Project for example, of which this renewable mapping supplement is a part, was designed to help increase investment and collaboration in renewables via engagement with government, industry and academia. Getting it right is easier said than done; even Chris Huhne, Whitehall’s Energy Secretary and a leading proponent of global action on climate change, recently lamented that his department’s regulations were of “a Byzantine structure, onerous for business, unworkable for government, and inefficient where it counts.”

But getting it wrong will be much more costly, both now and in the future, on a number of fronts: substantial fines from missed targets; insecure energy supply for homes and businesses; and lost jobs and prosperity from missed investment. The good news from the CBI’s report however was that the industry itself as well as the financiers that were interviewed during the course of the study, saw no insurmountable barriers to investment. Rather they were convinced that provided governments plot the right course of action to encourage low carbon investment, their economies can successfully complete the transition.

For further information please contact: Kirsty McManus, Joint Business Council

Programme Manager.

kirsty.mcmanus@cbi.org.uk