Digital transformation: An international perspective

Digital government approaches are the foundation for transforming a country, the OECD says. eolas analyses the organisation’s guidelines for such transformation, as well as international exemplars who have illuminated the path of transformation.

The OECD states that it works with member governments to “rethink their role, scope of activity and ways of working in light of digital technologies” and to make the move from e-government to digital government, differentiating the two by stating that e-government approaches prioritise technology as a solution, whereas digital government approaches prioritise “meeting the need of a user by re-engineering and re-designing services and processes” with technology as secondary.

The OECD’s Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies contains three pillars and 12 principles to “ensure the successful design, development, and implementation of digital government strategies to enable transformation”, as well as six dimensions of activity: a data-driven public sector; digital governance that is open by default; the use of government as a platform, “building an ecosystem to support and equip public servants to make policy and deliver services that encourages government to collaborate with citizens, businesses, civil society and others”; governance that is digital by design; user-driven design; and the design of proactive digital governance that “allows problems to be addressed from end to end rather than the otherwise piecemeal digitisation of component parts”.

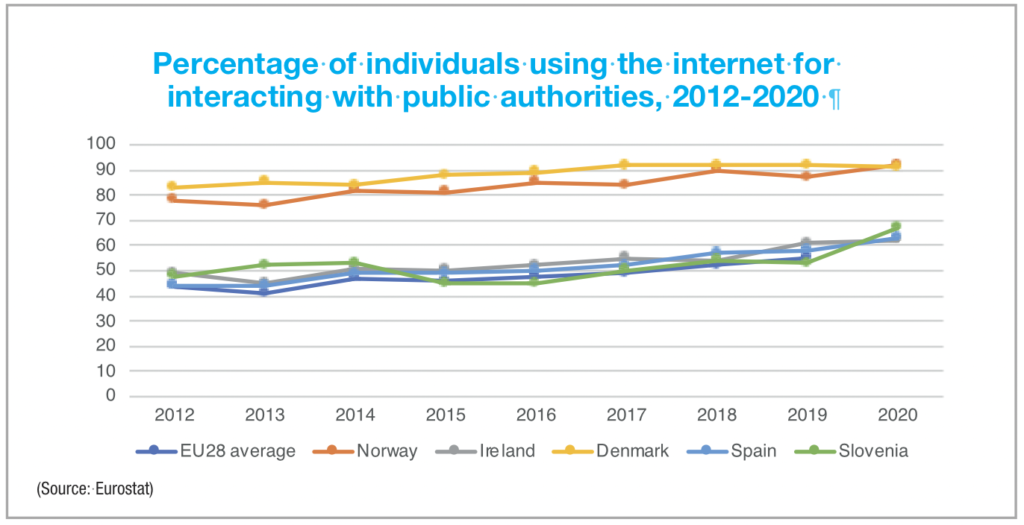

The effectiveness of such approaches is often measured via the metric of individuals using the internet for interacting with public authorities. Eurostat statistics show the average of the EU28 to have risen from 44 per cent in 2012 to 55 per cent in 2019, the last year to record statistics before the UK’s departure from the EU. Although not a member of the EU, Norway’s statistics are also included by Eurostat, and they show a notable rate, rising from 78 per cent in 2012 to 92 per cent in 2020; in comparison, Ireland has risen from 49 per cent in 2012 to 62 per cent in 2020.

Research by Elena Parmiggiani and Patrick Mikalef published in June 2022 states: “If we were to take a picture of everyday life in Norway, we would observe that almost every citizen in Norway adopts online banking; pays their bill online; interacts with public agencies through digital channels such as platforms, chatbots, and video-based meetings; performs their tax return electronically; and exchanges money seamlessly via mobile payment apps.” However, the research does also state that Norway has “struggle[d] to improve its performance in terms of digital public service delivery” but that its “healthcare sector has been an early attractor of significant investments toward a shared digital infrastructure (including data exchange standards and platforms) to share electronic patient records”. This has meant that Norwegian digitalisation has “so far been uneven but, overall, quite successful”.

Data-driven decision making is used in Norway for taxation and census purposes, and indeed Parmiggiani and Mikalef state their belief that Norway’s digital transformation began in 1967 with the creation of Folketrygdloven (the national insurance scheme), which provides a compulsory insurance scheme for all people in the country and considers factors such as age, health status, employment status, and maternity/paternity leave. Another example proffered is that of Altinn, a platform that began as a government portal for the mandatory reporting of companies’ financial statements, and is now used to support digital communication with the public administration for citizens and companies.

The Norwegian Government can now generate a citizen’s or organisation’s tax statement by integrating data across the national population registry and the national registry of business, banks, and insurance companies using Altinn. 2006 saw the adoption of the so-called ID-porten, a public authentication gateway that provides a standardised login and a flexible solution for different commercial electronic IDs to be used that facilitates the integration of services and user communication across public and private actors “to a degree that is almost unprecedented”. This is achieved because the “cross-silo integration it offers is possible because the Norwegian State is allowed to access citizen’s financial information with high granularity”, which “can only happen under the auspices of a trust-based (tillitsbasert, in Norwegian) system among State, citizens, and organisations”. Altinn, Parmiggiani and Mikalef write, “clearly illustrates that the public sector is a driver of digital transformation in Norway, as opposed to a simple adopter”.

Further afield, the example of New Zealand is often mooted as a country that has laid the groundwork over a long period and is now reaping the rewards of digital foresight. Having first used technology for government functions in 1996 and opening online government services in 2000, over one million citizens now interact with the government weekly through the Common Web Platform, a platform-as-a-service used to host government and public sector websites. The UN’s e-Government Development Index for 2022 ranks New Zealand fourth, the same as its 2020 rank, and its e-Participation Index ranks the country sixth. Ireland, in comparison, ranks 30th for development and 47th for participation, showing the progress that is both possible and left to be made up by a State with a similar population to New Zealand.