Energy security in an all-Island context

Brian Ó Gallachóir, Associate Vice-President for Sustainability at University College Cork (UCC), assesses whether worrying electricity generation inadequacy necessitates an all-island focus on energy security.

Ó Gallachóir heralds the development of the all-island Single Electricity Market (SEM) as one of the “hidden giants” of greater all-island cooperation, 25 years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

In 1995, the North South Electricity Interconnector was restored after almost 20 years of inaction and since then several significant electricity and gas infrastructure projects have been developed on the island, ranging from the commissioning of the Moyle electricity interconnector to Scotland in 2021 to the approval in 2018 of a second North South Interconnector.

While benefits to consumers have been evident in the delivery of cost reductions per kWh, the all-island market has also been critical to providing timely warnings on supply risks via generation system adequacy reports.

“These reports significantly helped enable us to look at the challenge of meeting our electricity demands through electricity supply on an all-island basis in an efficient and cheaper way,” explains the Cork-based academic.

“That focus on efficiency leads to emissions reduction relative to what otherwise would have ensued. Similarly, efficiencies also lead to price reductions, relative to if these markets had continued to evolve separately.”

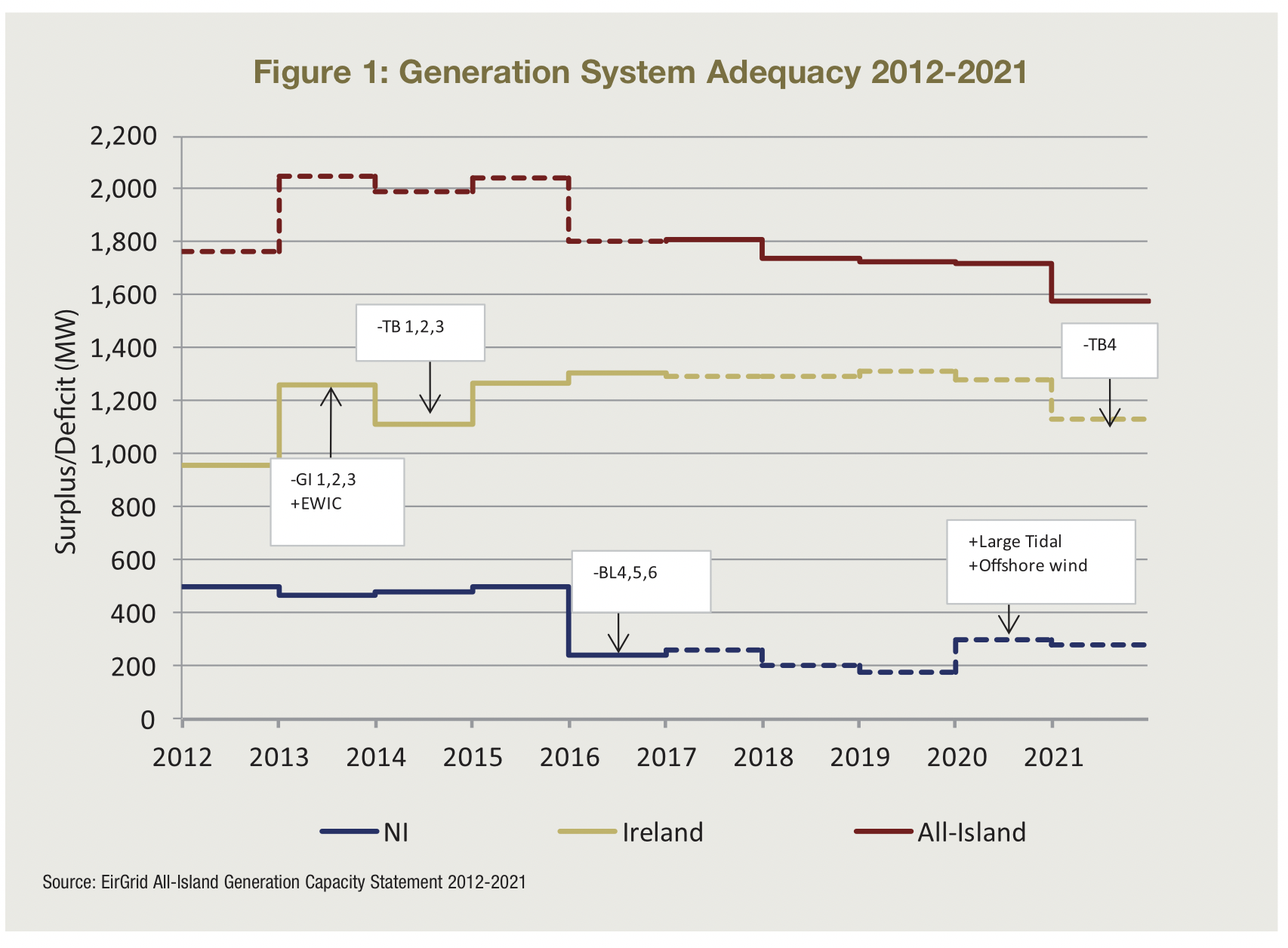

Significant infrastructure developments in the all-island electricity and gas networks have provided a high degree of reliability. The Generation System Adequacy report for 2012-2021 (Figure 1) shows large levels of surplus electricity on an all-island basis. However, the report also indicates tight margins for the North from 2016 onwards, providing an impetus to build and plan for the second interconnector.

“The signal at that time was important in terms of flagging what might be important,” says Ó Gallachóir, adding: “Rolling forward to 2017, we saw even starker warnings of the situation, but this time in both jurisdictions. This foresight has been very important in terms of informing the policymakers, the regulators, and the industry of the challenges ahead.”

In the past five years, energy policy developments have been significant. The transition of the SEM to the I-SEM as part of the European electricity market developments in 2018 was impacted by Brexit and in the last three years there have been strong policy developments relating to supply security, but also in terms of the energy transition to a low carbon future.

Both jurisdictions on the island share a number of ambitions in relation to net zero by 2050, including the target of an 80 per cent renewable energy share of electricity generation by 2030.

Key to achieving this ambition will be the increased focus on interconnection. The Greenlink Interconnector between County Wexford and Pembrokeshire, Wales is currently under construction with a commission date of 2024. The second North South Interconnector continues to face challenges but has a target commissioning date of 2026. Additionally, the Celtic Interconnector linking Ireland to continental Europe via France is set for commission in 2027, while the Lir Interconnector, connecting the North and Scotland, should be active by 2029.

One of the key achievements of the SEM has been the levels of variable, non-synchronous renewable electricity that has been integrated onto the all-island electricity network, which at times has breached 75 per cent. Ó Gallachóir explains that absorbing such levels of renewable generation on a small power system is “world-leading”, but points out that wind variability does mean there are instances when the share of wind-generated renewable electricity is low.

Security of supply

Highlighting the role of natural gas in providing energy security, the Associate Vice-President of Sustainability at UCC points to a period in early January 2021 of low winds and cold weather where the power system on the island compensated for the low levels of wind with increases in natural gas power.

“The level of flexibility and agility that our system has developed in order to deliver the growing amounts of wind energy that we have on the all-island system is another key feature that is sometimes hidden in our electricity supply mix,” he explains.

“It is important that we can maintain this going forward but it requires significant changes to electricity markets. There is a need to focus not just on the energy payments associated with the market make-up, but also the system services and capacity payments.”

Highlighting that auctions have not always delivered as much capacity remuneration contracts as required, which requires policymakers to rethink market support for new back-up generation capacity, he adds: “We have the theories in terms of how to support and remunerate for capacity, but unfortunately, we have not sufficiently delivered and this is why we have this short-term adequacy challenge.”

More challenging, Ó Gallachóir suggests, is the fact that many of the capacity remuneration contracts for additional gas-fired power plant which have been awarded, have not delivered on the amount of generation initially pledged that is required to be available at times of low wind speed.

This has led to a situation where in winter 2023/2024, the loss of load expectation is 21 hours. While this is less than the 50 hours recorded in winter 2022/2023, it is still well above the guideline of eight hours at most.

Ó Gallachóir explains that blackouts and brownouts have been avoided because of policy decision to extend older power plants that were scheduled to retire, and the procurement of temporary emergency electricity generation, which is more expensive, more carbon intensive, and does not represent a long-term solution to the challenge. Temporary electricity generation is in the main fuelled by natural gas.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent price hikes of imported natural gas shone a focus on Ireland’s reliance on fossil fuels to ensure energy security.

Although Ireland was relatively insulated from the physical risk to security of supply because of gas interconnections to Britain and a low Russian dependence, it is an outlier in the absence of gas storage.

Progress is, however, being made. The Government recently published an Energy Security Strategy, while in the North, the first caverns of the Islandmagee (County Antrim) natural gas storage facility are expected to be operational by 2026.

However, Ó Gallachóir says that in the context of progress of the all-island electricity market, the question has now been raised as to whether storage at an all-island level for gas should be considered.

Concluding, the academic raises some concern that the SEM and the benefits of an all-island approach – not least improved energy security – are underappreciated.

In the context of an ongoing demerger between EirGrid, the national electricity grid operator, and the System Operator for Northern Ireland (SONI), he says: “I would hope that as we move forward, we refocus our efforts on ensuring we look at energy security, not just through the lens of each jurisdiction, but on an all-island basis.”