Enhancing Ireland’s criminal justice system

With a clear focus on community-based sanctions in the recently agreed Programme for Government, Securing Ireland’s Future, we in the Irish Penal Reform Trust (IPRT) recognise a huge opportunity to prioritise and deliver on longstanding commitments to improve and enhance our criminal justice system.

IPRT has long advocated for the ratification of the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture (OPCAT), an international human rights treaty that Ireland first signed in October 2007. This instrument would assist the State in preventing torture and other forms of ill-treatment in all places of detention, an objective that is ever more pressing in the context of severe prison overcrowding. The good news is that we are already part of the way there to take this important leap forward as the Oireachtas Justice Committee has already scrutinised and made clear recommendation to improve the draft Inspection of Places of Detention Bill 2022. IPRT believes that it is essential that this new Government prioritises and enacts this legislation within its first 12 months in office, ensuring that Ireland is no longer the only EU country yet to ratify OPCAT. This is important not only from an international reputational perspective but to ensure that the relevant statutory bodies are empowered to ensure that inhumane and degrading treatment is prevented from occurring behind the high prison walls and in other places of detention including prison escort vans and Garda custody as well as in mental health and social care settings.

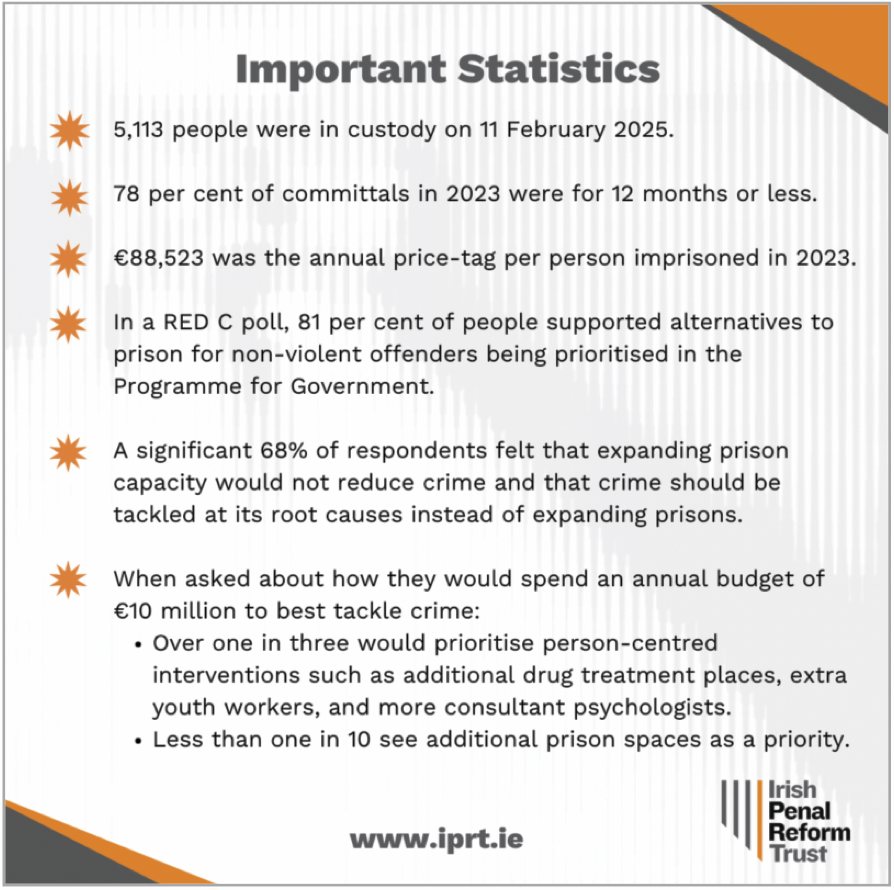

It is no secret that the penal system is under severe strain with record numbers of people in prison. Yet there are solutions that would not only address the overcrowding crisis but also tackle the underlying causes of criminality to the ultimate benefit of society. Over-reliance on imprisonment, especially for less serious and non-violent offences, has resulted in a significant number of people going to prison for short periods of time and it undermines rehabilitation efforts. Community sanctions and increased access to restorative justice, have a greater impact in reducing reoffending and are more cost-effective than imprisonment with its costly annual price-tag. These measures also align with public sentiment, with nationally representative public polling by RED C commissioned by IPRT in October 2024 finding that the vast majority of adults supported alternatives to prison for non-violent offenders being prioritised in the Programme for Government.

The new Government’s commitment to enact legislation to extend the use of community sanctions is welcome and will hopefully result in an updated and robust version of the Criminal Justice (Community Sanctions) Bill 2014 being enacted enshrining the principle of imprisonment as a last resort in law. A compelling example of how targeted legislative change providing alternative sanctions can directly reduce the prison population is the Fines (Payment and Recovery) Act 2014 which within the first two years of commencement, reduced the number of people committed to custody for non-payment of fines by approximately 80 per cent, as courts shifted toward non-custodial options for handling unpaid fines. While we unfortunately saw the number of people committed for non-payment of fines increase in 2023, it is a far cry from the thousands of people detained prior to the legislation coming into force.

While IPRT is encouraged by some of the progressive measures taken in recent years, we remain concerned about the much-lauded prison expansion of up to 1,500 spaces by 2030. As far back as 1985, the Whitaker Report (tasked with evaluating existing and future prison capacity) noted that “if prison places are available, they will tend to be filled”. Since then, multiple reports, including the 2013 Oireachtas Sub-Committee Report on Penal Reform, the Justice Committee’s 2018 report and the Strategic Review of Penal Policy in 2014, have all advocated for a cap or reduction in prison numbers to safe levels with a focus on increasing the number of open prison spaces. Yet the new commitment on prison expansion centres on building a closed prison at Thornton Hall. With a clear focus on more cost-effective community-based sanctions, and a welcome commitment to explore an open prison for women, IPRT would question the need for such a large-scale, costly institution. Evidence shows that increasing the size of and numbers in our prisons does not – and will not – reduce levels of crime.

At European level, other countries have been successful at closing traditional-style prisons and Ireland supported the European Council’s conclusions on the use of small-scale detention in June 2024. This concept is gaining traction at both the European and international level with a recent resolution passed by the UN Human Rights Council calling on States to introduce appropriate alternatives to traditional incarceration—such as small-scale detention — while prioritising non-custodial measures and options.

While prison and the criminal justice system is often perceived as falling squarely within the remit of the soon to be renamed Department of Justice, Home Affairs and Migration, if we dig deeper into who ends up in our prisons, we see that a whole-of-government approach is essential. We need to see more of the type of interdepartmental and interagency collaboration that produced the final report of the High-Level Taskforce on Mental Health and Addiction to divert people with complex needs away from the criminal justice system. IPRT believes a whole-of-government strategy for rehabilitation and reintegration could address many of the factors underpinning the issues faced by so many people that end up in our prison system. We look forward to working with the newly appointed Ministers and their officials and we remain optimistic that a more humane and progressive penal system is possible.

W: www.iprt.ie