Financing higher education

Underfunding of higher education is not only damaging the system, but also potentially forgoing opportunities offered under Brexit David Whelan reports.

The recent rankings by QS World University Rankings has shone a spotlight on under-investment in Ireland’s higher education system. Under austerity, cutting back on funding to Ireland’s colleges was recognised as an invisible cut. This problem was highlighted by Provost of Trinity College Dublin, Dr Patrick Prendergast, in response to the latest rankings when he said: “It appears easy for governments to reduce higher education spending because the cuts are often invisible at first and it can take several years for their damaging effects to become obvious. That day has now come. Today, we see the inevitable result of under investment.”

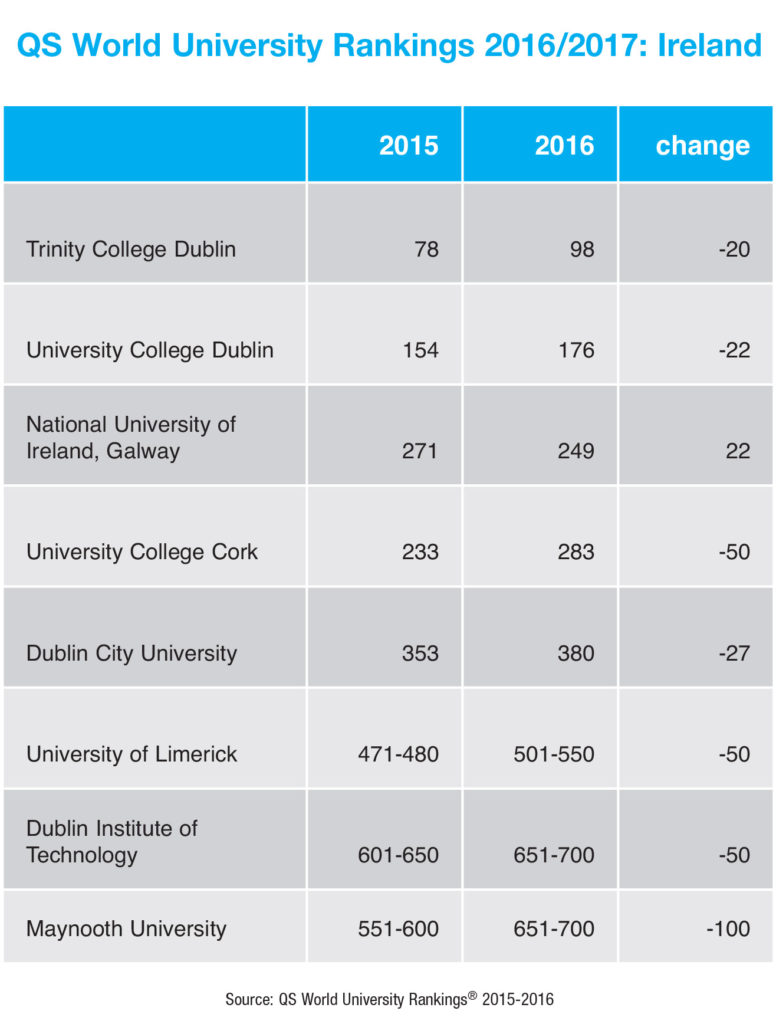

The rankings show that apart from the National University of Ireland, Galway, all of Ireland’s other universities fell in ranking in comparison to last year. Trinity College remains Ireland’s top-performing university at 98th place internationally, a fall of 20 places. The second highest ranked University in Ireland, UCD, fell 22 places to 176 and UCC fell places to 283. University Limerick fell out of the top 500 to the 501-550 bracket and both DIT and NUI Maynooth are now ranked between 651-700. NUI Galway climbed 22 places to 249 from 271.

The rankings slide brought into public consciousness a growing concern amongst the higher education sector in recent years. Aligned with the announcement both Prendergast and the President of UCD, Professor Andrew Deeks, released a joint statement outlining their concerns and urging the Government to implement the Cassells report.

They noted that declines suffered by the universities will have a long-term effect on investors, employers, prospective international students, academics and research. They also pointed to a soar in the student/staff ratio and an 18 per cent rise in student numbers, with warnings of a further 29 per cent increase up to 2028 from 2013 levels.

“As a small open economy which is heavily dependent on FDI and on the employment of highly educated staff, we cannot afford to fall behind our competitor countries in terms of investment in higher education,” the joint statement reads.

It adds: “As the presidents of the two highest ranked universities we now take the unusual step of calling jointly on the Government and opposition parties to implement the Cassells report. The political system must now make the difficult choices that are needed to improve the funding given to universities and in the manner in which this funding is distributed.”

In its final report published in July, the Peter Cassels-led expert group, tasked with outlining a funding strategy for the sector, stated higher education’s contribution to social and economic development was “severely threatened” under the current funding model and explained that that the latest increase in student numbers has been: “funded from internal efficiencies and by other cost cutting measures that, by and large, have been exhausted.”

In outlining the need for annual additional funding of €600 million by 2021 and €1 billion by 2030, a capital investment programme of €5.5 billion over the next 15 years and an additional €100 million towards a more effective system of student financial aid, the report suggested three options for extra funding including the scrapping of fees in favour of student loans based on employment income of a graduate, an increase in state funding of the sector from 64 per cent to 80 per cent and an entirely state-funded model.

The report has proven problematic for the minority Fine Gael Government. The unpopularity of an extra cost incurred on students for funding to the sector was highlighted by a national demonstration involving approximately 5,000 people in October. The volume of funding needed is also unlikely to be awarded solely from the State and a search for the political “consensus” outlined by Minister for Education Richard Bruton TD, suggests further delay in any implementation.

In October the Minister did announce an injection of €36.5 million for the sector this year, the first significant funding increase after almost a decade of cuts. However, critics argue that the three year funding package of €160 million falls far short of the funding required and plans to review a strategy for a bigger contribution from employers by April, still represents a significant delay. The review being carried out by the Department will coincide with the Oireachtas education committee’s assessment of the Cassells report.

The delay, as well as previous under-investment, has been pointed to as a hindrance not only to the current delivery of higher education services, but also the potential opportunities for the sector under Brexit. As Europe’s largest English-speaking nation after the withdrawal of the UK, Ireland stands to benefit from increased levels of academics, students and EU research funding. However, with the system in crisis, it has been questioned whether the current model would be fit to accommodate increased demand or interest.

Any change in the border scenario, where currently more than 2,500 students from Britain and Northern Ireland travel to the Republic to attend third-level education and 11,000 students travel in the opposite direction, threatens to disrupt a long-standing process, especially where a difference in fees exists.

However, one opportunity alluded to by senior figures in the sector is 15 per cent of the UK’s top researchers who are non-UK nationals and could eye Ireland as an attractive base.