FinTech: A path to regulation

Despite substantive EU moves to regulate the FinTech sector, Ireland has yet to formulate its own domestic policy on the technology, including cryptocurrencies.

Over a decade since FinTech’s core platforms rose to prominence, the sector remains in a period of protracted infancy. Despite its nature as a recognised technology and financial tool, investors and advisors continue to exercise caution around what is still a vastly underregulated market. As a means of addressing this issue, an EU Directive implemented in January 2018 was transposed into Irish law as the European Union (Payment Services) Regulations 2018 (PSD2), placing authority with the Central Bank of Ireland around ensuring financial regulatory compliance.

The 2018 implementation of the EU Directive can be interpreted as a robust statutory recognition of the FinTech sector’s unprecedented growth over the past decade. Whilst providing legislation to support the operation of the single market in payment services, the 2009 European legislation which previously underpinned the governance of FinTech was devised at the time of its commercial advent, leading to ambiguity in its modern interpretation and uncertainty around elements of the technology as it continued to evolve into the present day.

Protecting the consumer

Such ambiguity and uncertainties have, to an extent, been addressed through the implementation of PSD2: the Directive has outlined a series of regulations and requirements for all payment service providers (PSPs) to follow into the future. With a broader scope than its PSD1 predecessor, the directive takes account of the rafts of new services introduced to the sector and is now applicable to each actor across the financial services sector, including e-money issuers, credit institutions, gambling companies and social media networks.

Beyond providing for the regulation of payment services, the introduction of PSD2 may also be viewed as a statutory reaction to market feedback. FinTech’s recent entry into the financial market and its usage of alternative business models has been criticised as making it more difficult for customers to ascertain how and if a company is regulated, and what statutory rights remain available. The notable lack of traditional advisory and customer service models was addressed by a series of regulations which place consumer rights as a priority, an example of which being the reduction of customer liability for non-authorised payments from €75 to €50, with consumers now entitled to an unconditional right to a refund for non-authorised direct debits.

In regard to the sharing of consumer data, Irish banks will be required to provide third-party service providers with access to customer data. In cases where a payment service is denied access to a customer’s payment account, the bank who issued the denial must explain the reasoning behind the denial via a Denial of Service Report to the Central Bank of Ireland. Alongside these consumer-protecting provisions, the PSD2 also banned surcharges for consumer debit and credit card payments, both in stores and online. Indeed, it can be argued that the PSD2’s combined objectives of enhancing competition, facilitating innovation, protecting customers, increasing security and contributing to a single EU market in retail payments all contribute to a process which may be understood as a regulated and monitored democratisation of currency.

Regulating disruption

Whilst the passage of PSD2 filled essential regulatory gaps regarding the protection of the consumer, considerable gaps remain in the regulation of cryptocurrency networks. Like many elements of financial technology, cryptocurrency, and particularly Bitcoin, is approaching its first decade in existence. However, the Irish Government has yet to respond to its growth with any specific regulations or public policy. Indeed, cryptocurrency has not achieved recognition as either ‘currency’ or ‘money’ in Ireland, with the Central Bank of Ireland continuing to warn against the technology, highlighting its lack of status as a legal tender and a substantive lack of government regulation. The warning similarly draws attention to the extreme market volatility of cryptocurrencies, an absence of protection and frequently misleading information. Encompassing the CBI’s warning is a simple statement: “You should not invest money you cannot afford to lose.”

A recognition of concerns around cryptocurrency, including concerns expressed by the CBI, has seen its beginnings in a discussion paper on Virtual Currencies and Blockchain Technology, published by the Department of Finance in March 2018. The paper provides a broad overview of cryptocurrency, tabling considerations as to how virtual currencies impact consumers and companies on several fronts, including consumer protection; EU regulations; data protection; taxation; and contract law. Whilst the document doesn’t outline the Irish Government’s official stance on virtual currencies, a proposal to create an intradepartmental working group to coordinate and monitor developments in Blockchain may represent the beginnings of a regulatory process in Ireland.

Whilst the discussion paper doesn’t signal a preference to any specific public policy, it does address a number of shared international concerns which may form the bedrock of any future Irish legislation. The document states that such concerns have largely been drawn from a 2014 report from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) entitled ‘Virtual Currencies – Key Definitions and Potential AML/CFT risks’. In regard to the consumer, concerns include the presence of refund policies, data protection laws, the presence of complaints process and more. Beyond consumer protection, the concerns outlined by FATF include a capital gains tax on profits for virtual currency investors; guidance in relation to tax and consumer protection matters for state bodies; anti-money laundering compliance for entrepreneurs and businesses; a clear regulatory environment for foreign investment; appropriate standards for accounting bodies; and clarity of data protection for legal bodies.

Opportunities

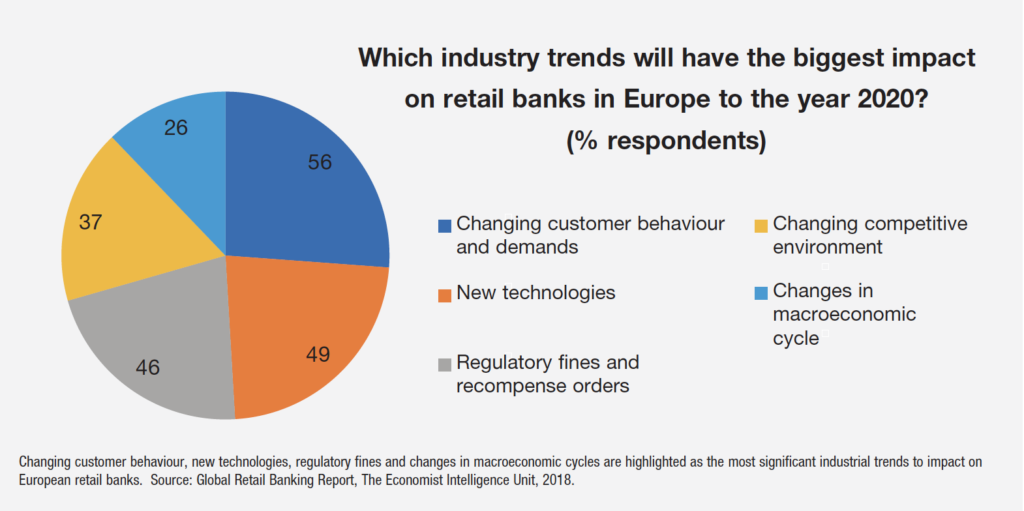

The Department of Finance’s recognition of opportunities granted by FinTech suggest a growing willingness of the State to move towards an official domestic policy around digital financial service providers and cryptocurrencies. Indeed, the discussion paper suggests that FinTech, and particularly Blockchain could assist Ireland in the delivery of its IFS2020 objectives “by fostering growth in the technology sector, while supporting indigenous companies and continuing to secure foreign investment”.

Indeed, the document assesses the collective value of the global currency market as roughly €320 billion at the beginning of February 2018, nearly four times the combined market capitalisation of the Irish Stock Exchange’s 20 largest companies, with the market value of bitcoin alone comparable to the market capitalisation of General Electric or McDonalds Corporation.