Global minimum corporation tax

The Biden presidency has reinvigorated efforts to reform the international corporate tax regime which could have significant repercussions for Ireland.

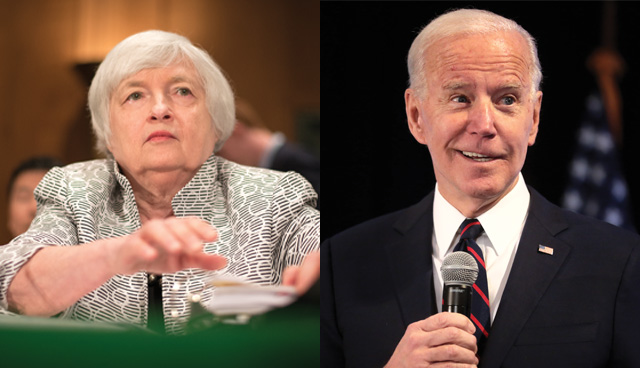

Addressing the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in early April 2021, US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen asserted that efforts to agree a global minimum corporate tax rate of 21 per cent could halt the “thirty-year race to the bottom on corporate tax rates”.

Yellen’s remarks on international priorities referred to efforts on behalf of some countries to use reduced rates of corporate tax as a tool of economic competitiveness in an effort to attract FDI.

“We are working with G20 nations to agree to a global minimum corporate tax rate that can stop the race to the bottom. Together we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations, and spurs innovation, growth, and prosperity,” Yellen said.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal in the same week, Yellen outlined: “This is the rock bottom of the race to the bottom: By choosing to compete on taxes, we’ve neglected to compete on the skill of our workers and the strength of our infrastructure. It’s a self-defeating competition, and neither President Biden nor I am interested in participating in it anymore. We want to change the game.”

Under Biden’s proposals, which have been shared with the 135 countries involved in the OECD BEPS negotiations, the taxes paid by multinationals would be based on their sales in each of the countries within which they operate. It is intended that this would inhibit tax avoidance and profit shifting. Meanwhile, the minimum global rate of 21 per cent could prevent the US from being undercut, stemming further losses to its tax revenue.

Speaking at a virtual meeting of the G20’s finance ministers in February, Yellen endorsed the OECD negotiations to reform the international corporate tax system. Two months later, the Treasury Secretary reiterated her support for an agreed OECD global minimum rate. “Destructive tax competition will only end when enough major economies stop undercutting one another and agree to a global minimum tax. Through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, we have been engaged in productive negotiations to achieve this,” she wrote.

This has revitalised the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project which seeks to mitigate the shifting of profits from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions by determining where tax is paid and setting a minimum rate. Pascal Saint-Amans, Director of the OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, suggested that the US proposals will “reboot” the stalled OECD negotiations.

GILTI

Domestically, the Biden administration intends to increase corporation tax to 28 per cent to provide revenue for a massive $2.3 trillion capital spending programme as the spearhead of the post-Covid recovery in the US.

Introduced under the previous Trump administration, the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) system taxes income that is earned outside of the US by US controlled foreign corporations. Intended to discourage US companies from offshoring business to low-tax jurisdictions, it is now recognised that 10.5 per cent was insufficient rate in disincentivising these companies. Biden’s proposals would increase the GILTI from minimum of 10.5 per cent to a minimum of 21 per cent.

If the Biden administration’s proposed changes to tax levying were implemented, it would mean that any company paying tax at a rate below the global minimum would be required to pay additional tax in each jurisdiction it operates in, in order to reach the 21 per cent threshold. Consequently, Ireland’s advantageous tax regime could be destabilised.

Although yet to progress through the House of Congress, the minimum tax rates set within the US will inevitably have repercussions for the OECD and Ireland.

While highlighting the fact that Ireland’s corporation tax rate has not changed since it was reduced from 32 per cent to 12.5 per cent in the 1999 Finance Act, Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe TD recognises that the context of the debate on corporate tax policy has now changed.

“What Ireland and other countries will do is put forward their case within with the OECD, and we’ll work inside that process to try and influence an outcome that recognises the role of small economies in the global economy,” he insists.