Green economic growth

Environmental policies should be designed to promote innovation and must take account of their economic impact, the OECD’s Brendan Gillespie tells eolas.

Environmental developments over the last decade “are not moving at a sufficient scale to bring about transition to a low carbon and more resource efficient society,” according to Brendan Gillespie, Head of the OECD’s Environmental Performance and Information Division. Addressing the annual Environment Ireland conference he said “more ambitious” policies are needed. Policy-makers need to remember that “investment decisions have important implications in terms of locking in the economies in which they function.” For example, transport infrastructure has a lifespan of 250 years, building stock has a lifespan of 150 years and power stations have a lifespan of 70 to 80 years. Therefore “capital investments create a dependency whereby future choices are constrained by choices that have been made in the past.”

Green growth is the key, Gillespie told eolas, because it involves “integrating economic and environmental policy and ensuring that economic policies are environmentally sustainable and that environmental policies take account of their economic impacts.”

He defined green growth as a means of “catalysing investment, competition and innovation which will underpin sustained growth and give rise to new economic opportunities.”

Gillespie explained that in the current economic and financial crisis “governments are looking for new sources of growth and employment and there is a hope that environment issues could be the answer.”

Gillespie explained that in the current economic and financial crisis “governments are looking for new sources of growth and employment and there is a hope that environment issues could be the answer.”

Fossil fuel subsidies in Ireland are contrary to the green growth concept, Gillespie told delegates.

Referring to the subsidies for electricity production from peat and domestic aviation and the tax concessions for coal and fuel oil which are used by households and farmers, Gillespie said: “The OECD suggests that if all fossil fuel subsidies were removed, this would reduce greenhouse gases by 10 per cent.”

He acknowledged that these are difficult politically but stressed: “From a green growth perspective, these fossil fuel subsidies are providing incentives for increased use of energy and the associated pollution.”

In terms of a water tax, Gillespie added: “From the perspective of people outside Ireland, it’s quite puzzling to see that households are not charged for water. At the end of the day either tax-payers or consumers [have to pay for it]. From an economic policy point of view, it would be more rational to charge consumers because that provides incentives for more efficient use of water.”

A new growth model

Environmental resources and services are vital for economic and social development because “they provide inputs into the production process and sinks for waste and pollution.” However, these services and resources have not been sufficiently valued in economic terms, according to Gillespie.

There is growing risk of crossing planetary boundaries i.e. thresholds, beyond which there could be irreversible changes in natural and environmental resources.

Political judgement is needed when deciding what a reasonable boundary and its political implications might be. In that context, green growth is a “conjunction” of the recognition of the risk of crossing planetary boundaries and the global economic crisis. It is the basis for a new growth model, Gillespie believes.

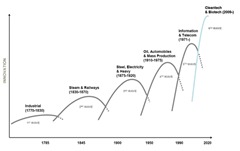

Because different technologies have played a key role in supporting different waves of economic development, such as steam and railways in the 1800s, (see graph) Gillespie stated that the question now is: “Whether environment and clean tech can be one of the drivers of a new economic growth?”

In ensuring polices that cater for green growth, Gillespie advised that “you need to be clear about the objective you are trying to achieve and you need to make sure that the benefits of the policy outweigh the costs.”

The cheapest way of achieving these objectives needs to be established.

He told eolas: “Increasingly, there’s recognition that one should try to design environmental policies in ways which create incentives for firms to find innovative new ways to achieve new objectives. Environmental policies shouldn’t prescribe the means for achieving the objectives but should give flexibility and incentives to achieve those objectives in new and least cost ways.”

Policies must also be designed in a manner that promotes innovation. This means they must contain a continuous incentive to innovate, be predictable (thereby reducing investor uncertainty), flexible (therefore not allowing limits on means to achieve the objective), stringent and targeted towards getting as close as possible to the real cause of the environmental problem.

“A range of different policy instruments are needed at different stages of the innovation cycle,” Gillespie recommended. This includes investment in R&D at the early stage, to more technology-specific instruments at the next stage, to finally removing the barriers to wider infusion of the technologies.

Gillespie added that the number of environmentally-related patents in Ireland as a share of the population is not very high compared to other countries and suggested that “some reflection could be given to how the broader innovation system in Ireland could strengthen its environmental component.”

He concluded by clarifying that “growth is not the same as GDP”. Instead, green growth looks at a broader range of measures such as the resource and pollution intensity of the economy in different sectors, how to take better account of changes to the stocks of natural resources, environmental quality of life and getting better measurement of the economic opportunities, such as trends in eco-innovation and the environmental goods and services industry.