Growing the real economy

The new Government faces “daunting but not insurmountable challenges on the economy”, according to ICTU’s economic advisor Paul Sweeney. He believes that policymakers must learn from history and avoid making the same mistakes again.

The new Government faces “daunting but not insurmountable challenges on the economy”, according to ICTU’s economic advisor Paul Sweeney. He believes that policymakers must learn from history and avoid making the same mistakes again.

The Celtic Tiger phase of growth was always temporary. It was rapid catch-up on Europe and we did so magnificently. There was a real boom for 15 years to 2001.

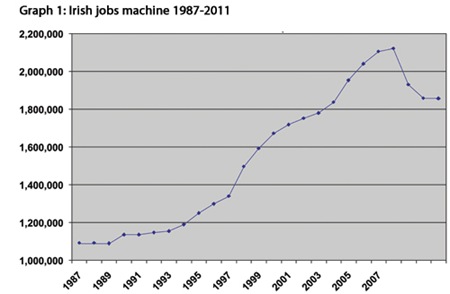

The strong economic growth lifted Ireland onto a modern plane. It was based on superb productivity growth in most sectors and on other real economic factors. This resulted in a phenomenal increase in jobs. There was almost a doubling in employment in a short period of 20 years, as graph 1 shows. This was an astounding achievement for a developed economy.

And incomes also grew, with take-home pay almost doubling, thanks in no small measure to massive cuts in direct taxes on incomes and corporate income. However, these cuts were sowing the seeds of destruction. Until 2001, the increases in wages, profits and jobs had been real, being based on productivity.

However, the seeds of the crash were sown from the late 1990s. In essence, these were the direct tax cuts, which went too far, deregulation and the naïve belief that “what was good for business was good for Ireland”. This was what the Financial Times called “Irish crony capitalism.” Any tax break, subsidy or de- regulation, however un-costed, was seen as good for business and as being good for Ireland, by many in business and by senior public servants.

Europe’s very low interest rates and liquidity meant that Irish banks were throwing huge loans at any buffoon. This should have been countered by a good regulation. But regulation was deeply unfashionable; foolishly seen as “anti- enterprise”.

Furthermore, pro-cyclical tax-cutting and a radical restructuring of the taxation system away from income tax to a dependency on consumption taxes, combined with un-costed and ultimately pro-cyclical and destructive tax breaks, went unchallenged, except by Congress. We were dismissed as party-poopers. Dissent was ignored. The effective tax rate on average industrial workers was cut from 23 per cent of income to just 11 per cent in the four years to 2001, by Charlie McCreevy. Being social partners did not have any weight as ‘Irish crony capitalism’ seemed to be working during the euphoria of the false boom of 2001- 2008.

The Government boosted the property boom-bust and ultimately it blew the gains of the boom. The recent Wright report on the Department of Finance asserts that the officials did warn, but produced no documentary evidence, beyond annual Cabinet memos which conveniently cannot be examined under FoI.

Ireland: the world’s worst performer

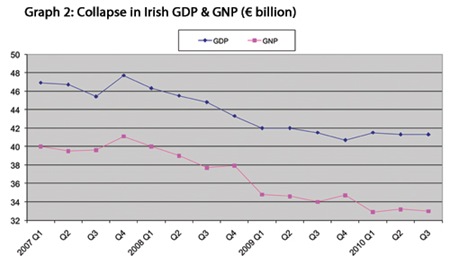

Ireland’s collapse in gross national product (GNP) was the worst in world. It is worse than Iceland on some numbers. For example, Ireland’s GNP has fallen by more than one-fifth since 2007 when it was €161 billion. GNP this year is down at €127 billion, which is slightly below that of 2003. We have suffered eight lost years of national income. In contrast, Iceland’s gross national product (GDP) fell by 7.9 per cent (our GDP fell by 14 per cent, but GNP is the better measure).

The governance system failed. Markets were so free that new rules were written by the key players for themselves. This was the result of the model of ‘shareholder value’ law for companies. But the regulators also failed, and government failed. There was lack of co-ordination, e.g. not having a financial regulator in the eurozone.

There are hard lessons to be learned. First, in spite of the anti-public sector rhetoric, governments are back in market, as big players. And they too made big mistakes – like the bondholder guarantee, de-regulation and privatisation. The bailouts are far from complete. Some banks, financials etc. should have been let fail. Many businesses are failing, including many good firms. The financial regulators finally woke up. Governments are cooperating internationally on tighter regulation and market rule-making.

Deflation has failed

National income has fallen massively by 21 per cent from peak. Prices are down but core hourly earnings are holding fairly steady in the private sector, though with reduced overtime and premium hours, overall earnings are down substantially. This indicates flexibility. Unemployment soared to 13.5 per cent and is only ‘stabilising’ because of mass emigration and falling participation.

As graph 2 shows, economic growth ceased in quarter four of 2007 and has being falling since, with small rises in quarter 4 of 2008 and quarter 4 of 2009. Growth of at least 2 per cent in GDP is normal in a developed economy. This graph of collapse in national income is extraordinary bad, unexpected, but worst of all, it was largely avoidable if proper policies been pursued during the boom years from 2001 to 2008.

The Irish economy in spring 2011 is characterised by: sustained high unemployment and high emigration, falling participation at work, reduced tax revenue, falling economic growth, plummeted consumer and business confidence, sustained high bond rates and a staggering banking crisis, which threatens to overwhelm the state itself.

The new Programme for Government is on the correct path, but some ideas are badly wrong. It is on the wrong path because keeping to the three, then four, and now five-year period of recovery risks deflating the economy into the ground. Continuing to front-load the ‘adjustment’ through some mitigation is planned by making cuts, with not much tax revenue. It will continuing initially with the increase in taxes on all earners, and not on high incomes, passive incomes and wealth. However, it is promised that this will change. It is deeply disappointing that it does not seek burden-sharing from all private bank bondholders. It has however, promised to undertake real reform of corporate governance. Whether it will focus on the core problem of the ‘shareholder value’ model of governance and company law remains to be seen.

The recession will not end when there are two quarters of bare economic growth but when there is a sustained rise in employment. The consensus is that this will not happen for many years.

The main reason is the deflationary policies. These have decimated domestic demand, sucking money out of the economy, especially from welfare recipients and lower and middle income earners, killing business confidence and the massive cuts in public investment are real policy errors. The strategic investment bank is in the right direction but is bureaucratically cumbersome.

The correct solutions would be to:

• lengthen the period of recovery and roll back front-loading;

• implement judicious cuts and taxes but tax “broad shoulders”;

• boost public investment substantially, by €2 billion a year for three years to lift demand and address our many needs;

• boost the solidarity bond, have auto- enrolment in pensions and personal retirement savings accounts in state pension funds, which will generate cash for the state;

• reform corporate governance i.e. Irish company law (which may occur); and

• negotiate and/or burden-share with bank bondholders and European partner states.

Confidence may return and lenders may lend again soon as the new Government has a more sophisticated plan, despite some continuing policy errors. There is greater recognition that the economy is a dynamic organism. It cannot be cut to death to “make it” grow.

In Ir

eland, tax compliance is not a “moral” issue, nor is it even a “civic” issue. The culture of tax evasion is pervasive. Tax avoidance by corporations is seen as a duty (to shareholders) which is even encouraged by promotion of Ireland’s low corporate taxation regime, as “the cornerstone of our industrial policy”. When the “cornerstone” of our industrial policy can be whipped away by others, then the edifice is poorly constructed. Ireland needs to move from adolescent to adult economic policies.

Finally, a new system of social solidarity encompassing the new Government, employers, unions and civil society would generate confidence and investment in the domestic economy, ensuring rapid recovery. Together, we can build on the considerable strengths of the real economy, while dealing with the fiscal and banking crisis, by stimulating demand and jobs.