Healthcare statistics

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Irish healthcare had already found itself at crisis point in terms of waiting times, capacity and staffing numbers. eolas explores the pre-pandemic statistics for waiting lists, hospital overcrowding and the health service workforce.

Waiting lists

The number of people on hospital waiting lists increased in January 2020, putting an end to months of trend reversal after the figures for August 2019 set the State record for the greatest number of patients waiting for treatment. In August, the number of outpatients stood at 564,829.

Increased government spending on the National Treatment Purchase Fund (NTPF) had begun to alleviate the backlog before figures for January indicated an increase in both inpatient and outpatient waiting list numbers. The outpatient list grew to 556,770 people for January, an increase of 3,336 on December, while the inpatient/day rate was 67,303 an increase of 740. Long-term outpatient waiting (18 months or more) numbers also rose from 102,924 to 107,040.

There was a large increase in the number of people on waiting lists given scheduled dates for their admissions – a 16.41 per cent increase from 17,211 in December 2019 to 20,033 in January 2020. Overall cases on waiting lists increased from 671,489 to 677,344. This is a significant surge in the context of the decline experienced in the fourth quarter of 2019, especially in December when the number outpatients waiting fell by 10,000.

The decrease in outpatient numbers was attributed to increased spending on the NTPF, which purchases treatments for public patients, often placing them in private settings. The NTPF’s 2020 budget is €100 million, a significant increase on the 2019 figure of €75 million. The fund has also been placed in charge of validations, the process by which it is determined whether or not people need to still be on waiting lists. The Irish Times revealed that the NTPF had carried out 75,000 validations in the final three months of 2019 after none had been carried out in the first nine months. 45,270 patients were removed from the outpatient list through this process, the majority of them because they did not respond to correspondence.

“In a submission to the Oireachtas Joint Health Committee in November 2019, the INMO said that in the last 10 years the Irish health service has “undergone unprecedented demand and changes have affected every aspect of the service, its clients, patients and staff”, especially during the period of 2009-2014 when health funding contracted by €4 billion in real terms. They also say that nursing and midwifery levels have not recovered to date from the 2007 staffing moratorium.”

Overcrowding

Annual figures from the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation (INMO) show overcrowding figures in Irish hospitals in 2019 to be the highest on record, with 118,367 patients left waiting for a bed after they had been admitted to a hospital.

The figures mark a 9 per cent annual increase from 2018, with September, October and November 2019 being the worst months for overcrowding recorded. 1,300 of those recorded waiting for a bed were under the age of 16. University Hospital Limerick was the worst hospital affected, with 14,000 patients left waiting on a bed after admittance there in 2019.

Following on from this, the INMO released figures showing the first full week of 2020 to be the worst across the seven days. A daily record of 760 patients was set during this week on both the Monday and the Tuesday. Once again, University Hospital Limerick was the worst affected hospital, with 322 people waiting across the seven days, followed by University Hospital Galway (212), Cork University Hospital and South Tipperary General Hospital (both 210).

The INMO has called for three measures to address the overcrowding crisis.

• “Restoration of recruitment powers to hospital groups, ending the recruitment freeze.”

• “Clarity on the 2020 funding for the previously agreed Safe Staffing Framework, which would set nursing numbers based on patient and health service needs.”

• “Rollout of the Sláintecare health reforms, which would offer more alternatives to acute hospitals.”

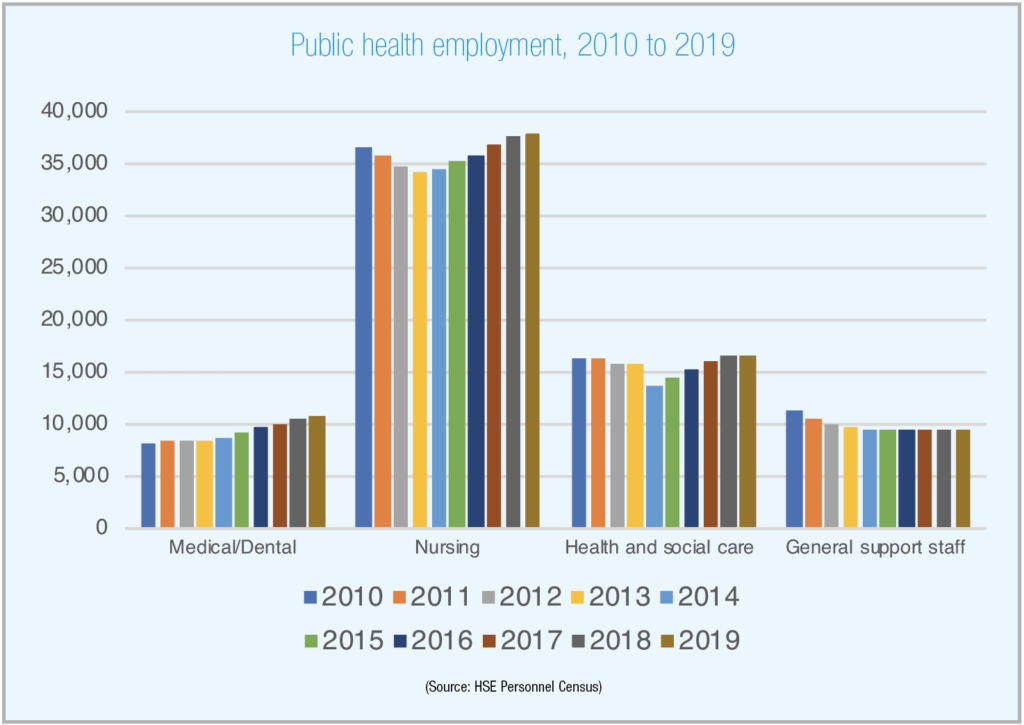

Workforce

In a submission to the Oireachtas Joint Health Committee in November 2019, the INMO said that in the last 10 years the Irish health service has “undergone unprecedented demand and changes have affected every aspect of the service, its clients, patients and staff”, especially during the period of 2009-2014 when health funding contracted by €4 billion in real terms. They also say that nursing and midwifery levels have not recovered to date from the 2007 staffing moratorium.

The shortage in nursing and midwifery “remains a real and worrying problem for the Irish heath service and for the workforce itself”. The whole time equivalent (WTE) employed at the time of the INMO’s submission stood at 37,843, 1,157 less than pre-2007 moratorium levels. The National Maternity Strategy determined that the minimum level of care for the health and safety of mothers and babies was an extra 200 midwifery WTE to be recruited across 2017 and 2018. However, midwifery WTE in Ireland has actually fallen since 2017 having stood at 1,461 in January 2017 and fallen to 1,399 by September 2019. This figure means that it is now the case that 262 WTE need to be recruited in order to meet the minimum requirements of a 2016 strategy.

The ongoing construction of the National Children’s Hospital is currently projected to add the need for 300 WTE children’s nurses, but the INMO points out that children’s nursing undergraduate and postgraduate programmes currently supply 225 WTE per year and will need to increase to meet the increased demands. They also suggest that contracts for these students be guaranteed in order to stem the flow of Irish nursing students emigrating.

|

The INMO closed their submission with the inclusion of eight measures to tackle the current workforce shortages. 1. Ending the recruitment pause. 2. In the medium term ensure an increased number of nurses and midwives are educated at undergraduate level. 3. Adequate funding and roll out of the Framework for Safe Nurse Staffing and Skill Mix in General and Specialist Medical and Surgical Care Settings in Ireland (National Framework). 4. Ensure that the growth of nursing and midwifery reflects the health care needs of the population, both now and into the future. 5. Develop clear and deliverable funded recruitment and retention strategies. 6. Develop a workforce strategy which will produce annual funded workforce plans. 7. Ensure that the working environment does not contribute to adverse outcomes for patients and staff alike. 8. Improve the supply of nurses and midwives by increasing undergraduate places and postgraduate places for specific disciplines in short supply. |

Sláintecare identifies the need for a further 900 nurses in the community, while the Capacity Review says that without reform of the health system, there will still be a need to recruit 700 public health nurses and 500 general practice nurses by 2031. At present, there are 210 undergraduate places for intellectual disability nurses, which the INMO says must increase in order to meet Sláintecare demands and “facilitate the person with an intellectual disability and their families, through all stages of their life, to take their rightful place as an Irish citizen”.