Hydrogen ‘essential’ to climate-neutral European economy

Hydrogen is “an essential component of the new, climate-neutral economy” writes European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans in a special report for COP27, during which hydrogen was heavily touted and a supply agreement with host Egypt was signed by the EU.

“In the current circumstances, investments in renewable hydrogen can also strengthen energy security and ensure industrial competitiveness,” Timmermans writes in his foreword to the report, Hydrogen: Enabling a zero-emission society, published by Hydrogen Europe. In the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and REPowerEU – the EU’s plan to end its dependence on Russian fossil fuels – the EU is aiming to produce 45 per cent of its energy from renewable sources by 2030, which would include 20 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen from an equal split of 10 million tonnes from both European production and extracontinental imports.

Hydrogen currently accounts for less than 2 per cent of Europe’s energy consumption and what hydrogen is produced is typically used to produce chemical products such as plastics and fertilisers. However, 99.3 per cent of this hydrogen production is completed through “conventional, polluting methods”. As part of the REPowerEU reforms, the EU announced a ‘full switch’ from the production of grey hydrogen to green. Indeed, the European electrolyser industry has committed to increasing its capacity tenfold to 17.5GW per year by 2025.

As the report was issued specifically for COP27, it was appropriate that the topic of hydrogen played such a heavy role in the discourse surrounding the event. This was, in part, due to the conference being hosted in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, which is one of the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) states eager to gain a foothold in the hydrogen market. Egypt is accompanied by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, whose Neom city-building project is said in the report to be “on track to sell carbon-free green hydrogen by 2026 for green ammonia producing, using 120 electrolysers to split hydrogen from water”.

The EU used the opportunity of the COP27 conference to announce the signing of a bilateral memorandum of understanding on hydrogen and renewable energy with its Egyptian host, which is on course to ensure that 100 per cent of national projects meet its green criteria by 2030, as it works towards achieving a 10 million tonnes importation target for 2030.

The memorandum will serve as a framework to support the long-term conditions of the hydrogen industry and trade between the EU and Egypt. Ultimately, the EU will contribute up to €35 million in support of Egypt’s Energy Wealth Initiative. This marks the latest in a series of hydrogen exchanges between Europe and the MENA region, with Germany having received its first shipment of low-carbon ammonia from the UAE in October 2022.

Hydrogen Europe estimates that 2022 levels of hydrogen demand currently stand between 8.4 and 8.7 million tonnes, with demand having more than tripled since 1975 according to the International Energy Agency and forecast to more than double from current levels by 2030.

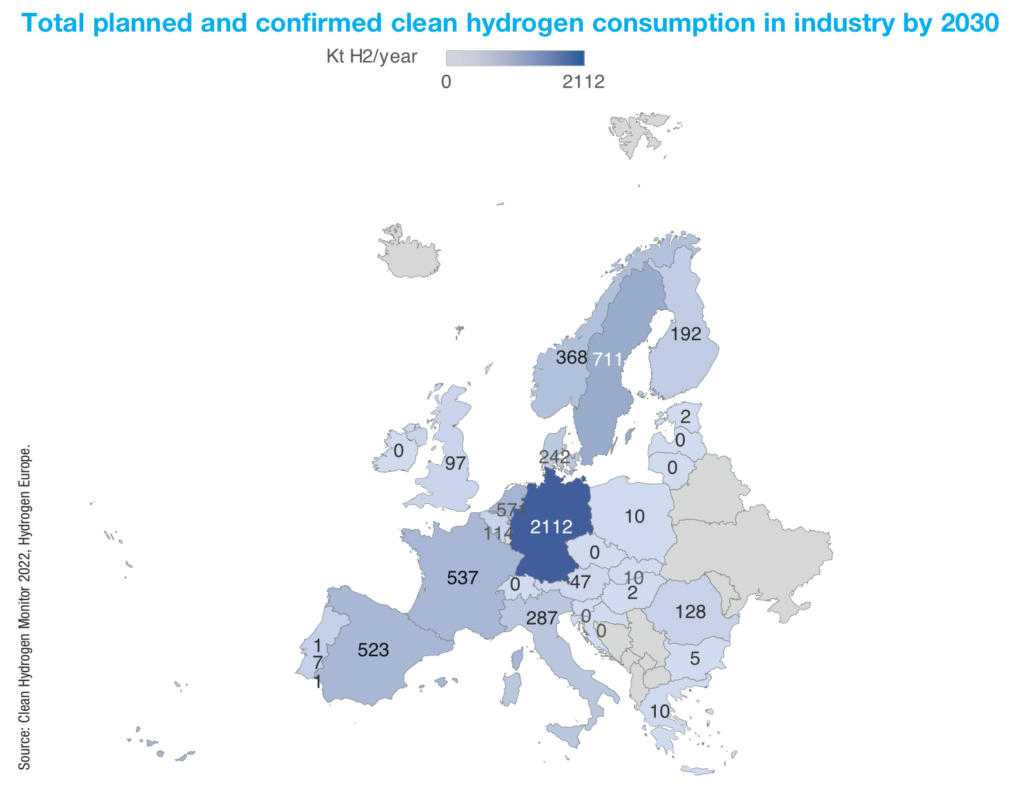

More than half of hydrogen consumption in the EU, EFTA, and the UK combined occurs in just four countries: Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Spain. Meeting REPowerEU goals will require investments between €86 billion and €126 billion, the European Commission estimates. Meanwhile, the Energy Transitions Commission projects that the decarbonisation process with hydrogen will require $15 trillion.

The European Hydrogen Backbone proposes the construction of 39,700km of hydrogen pipelines by 2040. It is anticipated that such widespread construction would play a role in reducing the price of the gas. The EU aims for green hydrogen to be available at a price of €2/kg by 2030. As things stand, the most affordable renewable hydrogen produced in the EU is produced in Portugal at a price of €3.50/kg.

Another key to such decreases in prices could be the extension of hydrogen production by thermolysis of sustainable biomass, which has no dependence on fossil fuels, with it stated by one producer in the report that the use of biomass allows for the production of hydrogen at costs of between €1.50/kg and €3/kg.

The decarbonisation of transport and other hard-to-abate industries will, of course, be central to both the European and global approaches to hydrogen implementation. Within the report, in a case study of French manufacturer Alstom, who designed, developed, and manufactured the first 100 per cent hydrogen train, it is estimated that 700 tonnes of CO2 – the yearly equivalent of 400 cars – would be saved annually for every train that is fuelled by green hydrogen.

For aviation, the report references the method of producing SAF fuel, which “employs a power to liquid (PTL) process, which relies on the supply of a sustainable carbon feedstock and the production of green hydrogen through electrolysis using renewable energy”. The carbon and hydrogen are then “converted to synthesis gas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, which in turn is converted to longer chain hydrocarbons for the production of jet fuel or SAF via the Fischer-Tropsch Process”.

European clean hydrogen capacity stood at just 162MW in August 2022, itself a notable increase from the 2019 level of 85MW, meaning that these plans are shelved for the time being.

In its European Hydrogen Strategy, the EU identified three development phases: kick-start, ramp up, and market growth. The kick-start phase has begun, and is expected to last until 2025, by which point “clean hydrogen will start to be competitive even without incentives in some production locations and industries”.

Achieving the 10 million tonnes of European production envisioned under REPowerEU will require up to 140GW of electrolysis capacity; announced projects already amount to 138GW according to the Clean Hydrogen Monitor.

For European hydrogen, the evidence will be apparent in the latter half of the 2020s. When the kick-start phase comes to an end and the ramp-up phase begins, it will become clear whether or not these plans have delivered real, built capacity.