‘I can actually breathe now’: A visit to the new Limerick Female Prison

Ahead of its official opening in October 2023, Ciarán Galway visits the new Limerick Female Prison to speak with Governor Andrew McCarthy, members of staff, and prisoners about the new facilities, the experience of women in prison, and the challenges faced by those working and living there.

Situated on Mulgrave Street, south of the River Shannon in Limerick city, Príosún Luimnigh is the oldest functioning prison in Ireland. A closed, medium security facility, it is the committal prison for adult males in counties Clare, Limerick, and Tipperary, and females in the whole of Munster.

Limerick Female Prison is one of two female prisons in the State, the other being the Dóchas Centre within the Mountjoy Prison complex in Dublin. Until the new standalone prison was developed, Limerick Female Prison was simply a wing of the male prison. Comprising two long and narrow corridors, the old female prison was frequently overcrowded.

Walking through the outer gates, we mingle with the families – mostly women and children – and friends of visitors. We are required to leave all mobile phones behind in the locker room. Entering the control room through a heavy steel door parallel to the main gate, photo identification is mandatory. Beyond an antechamber of turnstiles and security scanners, we enter the prison proper and, skirting a wing of the male prison, approach the female prison via an access yard. Topped with razor wire and anti-climb barriers, high limestone walls form the prisons octagonal outer boundary, enclosing men and women alike. But that is where most shared architectural legacies end. In fact, Limerick Female Prison is unlike any other prison in Ireland.

According to Architects’ Journal, Limerick Female Prison is now most akin to a Scandinavian correctional facility. This is in stark contrast to the old female prison, which was completed in 1821. It was one of five now mostly replaced spoke-like wings emanating from an administrative nucleus; highly innovative in its day, but totally unsuited to the 21st century.

Inside

Entering the reception area of the female prison to our immediate left are several cells, which are purposely left vacant. Not unlike the rooms of college student accommodation, each cell has a desk, kettle, small television, a bed, and – in a major departure from traditional cells – a simple, but fully partitioned, toilet and shower. Some of the more typical features include the anti-ligature curtains and blinds, alongside a long mirror installed within the window itself. It is the default configuration known to the majority of the female prisoners in Limerick.

Traditional viewing hatches have been replaced with smart glass which is a default opaque diamond but becomes transparent at the touch of a coloured plastic fob. The same fob, mimicking the silhouette of a traditional key, unlocks each digitally enabled cell door (with a failsafe analogue backup).

These trauma informed features are intended to reduce noise, minimise disruption, and avoid retraumatising each cell’s inhabitant. It is a fact that 90 per cent of women within the Irish prison system have experienced serious trauma, while 80 per cent have experienced addiction challenges.

Overlooked by the cells and the gym, the open-air exercise yard is unlike any other in Ireland. A slightly curved rectangular central courtyard, with a meandering tarred path, it is dotted with adolescent trees and evergreen shrubs, while wooden benches line the perimeter. A large stone water feature bubbles in the background, the cascading water creating a relaxing aura. One section is dedicated to a small play area for visiting children.

“We call it an exercise garden because it is not a yard,” the Governor observes. “Everything here is geared towards the women feeling safe, happy, and creating a positive environment.” Indeed, in this space, the only hint of prison architecture is the security net which criss-crosses the sky above.

The ‘on protection’ female prisoners’ yard has been also designed with trauma in mind. The grey façade of the tall precast concrete wall which contains one side of the yard has been painted with a mural of a bright faceless bird, while plants line the base.

As we re-enter the building, prisoners and staff greet the Governor. He responds on a first name basis. If teleported into the centre of the oval atrium from the outside world, it might be difficult to immediately determine the exact function of the facility in which you had found yourself. The clinical atmosphere betrays the fact that it is a public facility. Perhaps a modern hospital, a cancer treatment centre, or a care facility.

Well-lit and spacious, it creates an ambience which blunts the reality. Gentle curving white interior walls are adorned with artwork from students at the Limerick School of Art and Design. A large atrium invites sunlight to spill in, illuminating both levels of the wing. An internal safety net, a ubiquitous feature of prisons worldwide, is conspicuously absent. Vibrant splashes of colour break up the monotony of the floor.

Given a choice of incarceration in one of the State’s prisons, Limerick Female Prison would inevitably be most people’s selection. However, even an aesthetically pleasing prison is still a prison, and no amount of architectural camouflage can change that the women here exist behind locked doors, sometimes in solitude for up to 23 hours a day.

The Governor

Just inside the prison walls, accompanied by a young Irish Prison Service (IPS) press manager, stands an archetypal prison officer; a steely exterior with a deadpan delivery. A native of County Cork, with an accent to prove it, Andrew McCarthy is Governor of Limerick Female Prison.

Joining the IPS in 1987, McCarthy was stationed in Mountjoy Prison for a very short period before transferring to Cork Prison, where he remained for almost three decades. “I had some of the funniest days of my life in Cork Prison,” he recalls. “We had the banter; it was absolutely brilliant. I was with between 25 and 30 prisoners in a small workshop, and never had an ounce of bother. Those prisoners rarely, if ever, returned because, for the first time in their lives, they had structure and they developed a work ethic.”

In 2016, he moved to Limerick Prison with the intention of returning to Cork, but found: “The challenges, and the camaraderie with the staff and with the prisoners here is second to none in Limerick.” As such, rather than a 12-minute commute, he opted to stay and “finish my time out here”.

Until McCarthy’s appointment, Limerick Female Prison did not have a standalone governor. With no governor and inadequate, overcrowded, and decrepit facilities, the female prisoners lacked access to the provision of many therapies and activities until the completion of the new prison.

Describing the old female prison as “a Dickensian facility”, McCarthy contextualises the construction of the new building. “What we wanted to create here, and what we put a lot of thought into, is a safe environment for the women so that when they go into their rooms at nighttime, it is their safe place. Everything we do is for the good of the women in our custody. By doing what we are doing, it is also making conditions better for the staff.”

Tackling the challenges faced by prison staff in the course of their careers, McCarthy is plainspoken. “Working in a prison can be one of the most rewarding jobs because it can be tough, but when you see people come in the state they do and then you watch them leave as a better person – many of them,” he says.

“On the other hand, you will have challenges along the way. It is not nice for a member of staff to check a cell at nighttime and to see that a prisoner has taken their own life inside the cell. No matter how good you are, or how tough you are, you take that home with you. One of the bonuses for me being in Limerick is that I have a long drive home in the evening, so the job is gone by the time I arrive.”

Trauma informed practice

Working in a female prison is different, the Governor asserts. “A raised voice can trigger a lot of emotion in here. You will very rarely hear a raised voice from a member of staff in here because we cannot have the trauma experienced by these women being triggered.

“Most of the women that come in here have suffered some form of trauma in the past, whether physical assault, sexual assault, or coercive behaviour, there is a whole realm of different forms of abuse and every one of them are represented in here. We needed to put a plan in place to help the women cope both inside prison and outside. For the moment, we have it right,” the Governor comments.

“We went through years with a one-size-fits-all approach in the Irish Prison Service. Male and female prisoners were treated the same. In reality, it does not work like that. The female need is different from the male need. Though I am not saying that male prisoners have not experienced trauma, because many of them have.”

Now, Limerick Female Prison offers a wide range of services to prisoners, from trauma informed education courses and psychology, to rape crisis intervention. “We implemented the trauma informed practice, and Bedford Row Family Project ran it for us and brought in outside agencies, such as ADAPT Domestic Abuse Services,” McCarthy outlines, adding: “We found that after a few weeks, a lot of the emotions were coming out when the women went back to their cells. As staff, we had to deal with that. We have ADAPT providing training to our staff now so that they are fully capable of dealing with that challenge.

“We also invited Coolmine Therapeutic Community in for one day a month. Coolmine is preparing the women for residential treatment at the end of their sentences. We address the trauma sphere on the inside and begin addressing addiction challenges, a process which is then completed on the outside with residential treatment delivered by Coolmine.

“For the first time ever, in Limerick, we are addressing the full spectrum of challenges faced by the female prisoners. We might not see instant results, but in six to 12 months, we anticipate drastic results in terms of reduced recidivism. While it will never totally dissipate, we are hoping that the work we are undertaking will ensure that many of these women will not return to prison.”

Prison experience

Beyond the centre are the enhanced prisoner suites which resemble immaculately kept studio apartments. Here we meet Martina. Martina is a life sentence prisoner who is 12 years into her sentence. In effect, Limerick Female Prison is her home.

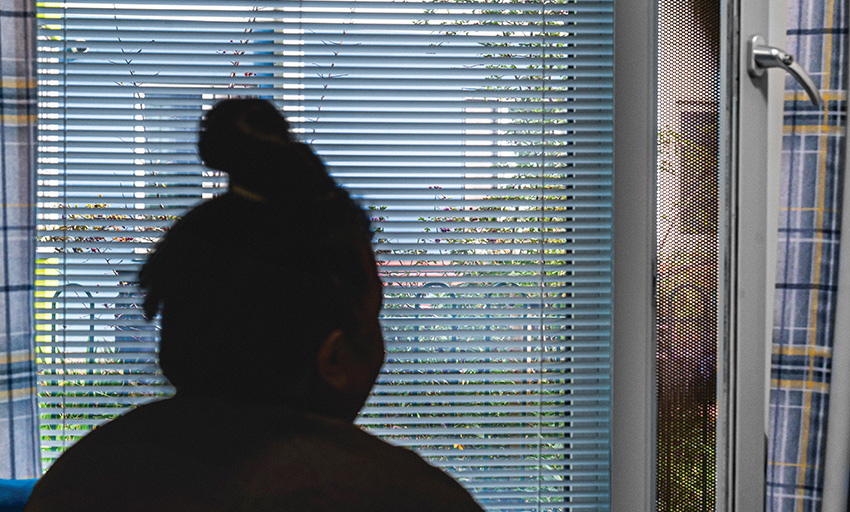

“We have windows to look out. It is like, ‘go to the window, Rachel, you can actually breathe now.’ To me, that is huge.”

Rachel, female life sentence prisoner

“I am 11 years and two months in Limerick. I was several months in the Dóchas Centre. I knew I was coming to Limerick, and you hear so many bad things – because this was my first time in prison – about Limerick Prison. ‘Oh, it is a real jail,’ people said. Coming to the gate was a daunting experience to say the least because I had all these images in my head, but I would say that in less than 24 hours it was all alleviated,” she explains.

At that time, she was a second-year undergraduate student of applied social science and community work degree at University College Cork, Martina anticipated that her education would be cut short. “When I arrived, the head governor, Governor Kennedy, asked if I had any concerns and I said that I would like to continue my studies. Straight away he told me to go to the head teacher. That has been ongoing now. I am just starting my social science master’s degree, but I received a postgraduate diploma in psychology recently.”

Discussing the most significant challenge of coming into prison for the first time, Martina recounts: “From my own experience, aside from the guilt, it was the loneliness. That is why I keep so busy, to get rid of that loneliness. By night time I be exhausted. I do 30 hours of study a week on top of everything else. I treat it like the outside and keep busy all the time.”

Speaking to the female experience of prison, she suggests that “women have different emotions; we express our emotions more” whereas, she contends that through interacting with male prisoners the opposite tends to be true for men. “We [women] cannot hold back. It is innate. It is the way we are. I know that the governors have taken that onboard and that is why they have brought in so many different programmes for us. Outside of general studies, there are several different programmes going on here; domestic violence, the rape crisis counsellor, and a gynaecologist who comes in to do group discussions with us.”

Discussing her future, Martina indicates that she has “always had hope”, adding: “I am 12 years in, and I am doing a life sentence. But I just treat this as my home now. I know that I am in prison and people say there must be something bad. I can genuinely tell you that the day I came to prison it changed my life forever. I see the effort that the staff make – most of the staff. I could not ask for better.

“Several years ago, there was a time when I felt very low – I had suicidal thoughts, I was arranging it in my head – and Ms Crowley and another female officer, Ms Dwyer helped me through that. I could go to them. I will always be indebted to the staff. Always.”

Discussing moments of loneliness and frustration, or coping with unwelcome news from her family outside, Martina is candid: “I sit back and say, ‘well look, this is my home for now.’ I do not know how long, and I do not think about it. It is better to not think about it and focus on what is happening to me now. I will be focused on my studies for the next eight months and then I will focus on whatever is next. Prison allowed me to face a lot of my challenges. It challenged me and I needed it.”

First impressions

Next door, Martina’s neighbour is a Cork woman, Rachel. “This is my third [time in prison], but I would not have been in here since 2010,” she begins, adding: “When I came in, I was all over the place in the old jail, before we came over here. The statement I used when I was in the old jail was that you leave your dignity at the gate, and you collect it on your way back out. This [new facility] is bigger, open, and nicer.”

Elaborating on her impression of the new female prison, Rachel is reflective: “When I came over here [to the new prison], I was asked a question about the new building. I was doing a group [session] and we had to pick out pictures. So, I picked out an old-fashioned picture of someone looking out a window. [The coordinator] asked what the picture meant to me. ‘For me,’ I said, ‘breath.’ I can actually breathe. We have windows to look out. It is like, ‘go to the window, Rachel, you can actually breathe now.’ To me, that is huge.”

“It is not our job to punish people. Punishment enough is coming in these gates and hearing a steel door close behind you every night at 19:00.” Martin Breen, Chief Officer

Four years into her life sentence, the Cork native discusses her experience of fellow prisoners coming and going. “It can be challenging when you hear that people are going home. It can be. But I just try to park it. I park a lot of things. That is my way of coping and how I get through every day. I know I am in here for a crime, so I am going to use it [the time] to further my education. I go higher and higher.”

On a weekly basis, Rachel works two days in the laundry – Wednesdays and Saturdays – while studying ICT, business studies, and maths. On top of that, she is a Red Cross facilitator and a Listener, a role she believes is “really needed in prison”.

Delivered by Samaritans volunteers and supported by the Irish Prison Service, the Listener scheme is a peer-support programme which aims to reduce instances of suicide and self-harm. Specially selected by the Samaritan volunteers, prisoners are trained to offer confidential emotional support to fellow prisoners who are struggling to cope or feeling suicidal.

“People coming in for their first time, or even if they are here a while, are vulnerable. I can understand where the vulnerability comes from. At the moment, I am with a girl and trying to help her as I go along, letting her know that she is not alone and there is support in here.

“For me, personally, when I came in, I was not looking for any support in that I did not know how to go about it. But I am here four years now, I have found out who I am, what kind of a person I am. But I worked hard on myself to do this.”

Looking as far ahead into the future as she allows herself, Rachel concludes: “My personal experience of coming to jail, with the officers and governors, [is that] they are very respectful. Very. And I am very respectful back. You can lean on them if you have a problem; we all have certain officers that we pick. Governor McCarthy took over as head governor and the courses that he has brought in for the women, including myself, are just fantastic.

“The course that is running with ADAPT about domestic abuse and sexual abuse is fantastic for the girls, even for myself, because it brings you right back. Tomorrow is our last day so the girls will receive a certificate. That will boost their confidence. Plus, Governor McCarthy has a lot more courses coming up for the women in here, again including myself.”

Chief Officer

Alongside Chief Clarke, Martin Breen is the Chief Officer in charge of Limerick Female Prison. “We supervise the day-to-day running of the new wing,” he begins, explaining: “We were both brought in specifically for the new wing. I spent the last five years in PSEC [Prison Service Escort Corp] and he [Chief Clarke] was in Portlaoise.”

Having joined the Irish Prison Service in 1989, the Laois man spent his first 10 years in Mountjoy Prison, before transferring to Limerick Prison in 1999. After a year working in Portlaoise Prison, he returned to Limerick in 2003 where he ascended to Acting Chief Officer. In 2018, he was promoted to Chief Officer and spent five years in charge of the Munster region with the Prison Service Escort Corp (PSEC), liaising with all court escorts from Cork and Limerick prisons around the rest of Munster and the State.

Quietly spoken and quick to smile, Breen’s 33 years of experience working in the Irish Prison Service are etched on his face. Having spent many years in the old female prison, he had always intended to return to Limerick. “Having witnessed this place being built, I was looking forward to coming in here. It is one million times better than where we came from. It is a fantastic facility. I am back in here in Limerick for the foreseeable,” he remarks.

Reflecting on the old prison, he emphasises its unsuitability as both a working and a living environment. “Now, you have seen the facility we have here. We have 56 beds and we have only one double cell at the moment. It is working. There is an air of calm around the place. It is noisy when it is unlocked; the noise travels. But there is an air of calm.

“The biggest challenge, or the biggest complaint we had from the women for the first two weeks when they first came over was that they were lonely. They [the prisoners] were in rooms on their own; they had never been in cells on their own. They were used to being doubled up and trebled up in cells. It was our [the staff’s] biggest worry too; that the loneliness would be too much to bear for some of them. The staff, to their credit, kept a good eye to make sure that everyone was safe, day and night, and the checks were done.”

With regard to his role as “the Governor’s eyes and ears”, he explains: “There is an Assistant Chief Officer in charge of the wing. If he has issues that he cannot deal with, he comes to me. If I cannot deal with them, I go the Governor, and vice versa. I have responsibility for the staff and the prisoners. I take that seriously. I look out for everyone.”

Describing the job as having evolved virtually beyond all recognition in three decades, he articulates his guiding principles: “We are not here to judge people. It is not our job to punish people. Punishment enough is coming in these gates and hearing a steel door close behind you every night at 19:00.

“While we are here, we look after them [the prisoners] as best as we can. In the 33 years, my number one rule has always been: be fair to people. Treat people the way you like to be treated yourself. I talk to the women on the landing the same way as I talk to you. Treat them as normal people. If they are entitled to something, give it to them. If you promise you are going to do something for someone then do it as best as you can. Do not make promises you cannot keep.”

Discussing the specific needs of female prisoners, the Chief Officer explains: “They are away from their children, their families, and their husbands. We also must remember that most of the women here are coming from experiences of domestic violence, sexual violence, physical violence on the streets, they are being pimped, they are trafficked into the country to steal or for prostitution. They have a distinct set of problems than the male prisoners. We must be cognisant of that.”

Linking with external services

Naomi O’Dwyer, the Integrated Sentence Management (ISM) Coordinator in Limerick Female Prison, radiates the rare energy of someone who genuinely loves their job. An ISM Coordinator is a prison officer who works with prisoners to provide a sentence plan which incorporates initial assessment, target setting for engagement with a range of prison-based services, and periodic reviews to measure progress.

Achieving this requires collaboration with prison management and the prison-based multi-disciplinary team, comprising the psychology service, the education service, the work training service, the chaplaincy service, the Probation Service, the resettlement service, the addiction service, and the prison healthcare team.

“Generally, once a prisoner is sentenced, we meet with them and set up a sentence plan for their time here, what we can achieve with them, and setting up supports in the community afterwards,” the Limerick native explains.

“Another element of the job is getting them [the prisoners] out on early release schemes, if we think they are suitable, where they can go out and work in the community three or five days a week. I must have very strong links with external services as well as internal services. I was working in Cork Prison for the last four years, with the male prisoners. I would have set up a lot of connections in Cork which I have brought into Limerick Prison for the females; we have a significant percentage of women from Cork in Limerick Female Prison.”

“I love it. I love working with the women. A female can achieve more with a woman; spending more time with them and supporting them better. There are different boundaries when you are a woman working with male prisoners.”

Elaborating on this theme, O’Dwyer articulates her perspective than an all-female prison is much more complex than an all-male prison setting. “When you walk into a female prison, it is louder, it is more vibrant. Women need more things every minute of each day. Much of this comes down to emotional support.

“Female prisoners require more attention because they are emotionally tied to the home. When they come in here, it is a lot harder for them. I am not saying that men do not miss their children, but the women carry more guilt around when they come in. Part of the research I did a few years ago found that when men come in, they tend to leave their baggage at the gate. They come in, do their sentence, and put their head down. Women do not tend to do that.”

Governor McCarthy echoes this sentiment. “When a women comes into custody, she is basically forgotten about,” he comments, before detailing: “The first thing a man does when he comes in is ring his partner, wife, mother, or sister, asking for clothes and money. Within a few hours the women are up to the gate. When a woman comes in, often no one answers the phone. She is left on her own. She has the worry then. Are my children being taken care of? Will I have a house when I get out? Is the mortgage being paid? Is the rent being paid? The man does not have that, the woman does, and we must deal with all that. That is reality. Women are basically a forgotten species when they come to prison. They are on their own.”

On the new prison infrastructure, the ISM Coordinator believes that it has been mutually beneficial for prisoners and staff alike. “For the prisoners alone, it is amazing to have the space, the light, everything they have here. The difference is amazing. The mental health of staff and prisoners is hugely improved because of the working conditions.

“I am still getting used to it because I was in the old female prison for 15 years. It is a very small area; literally two corridors for all the prisoners and the staff. It just makes it much harder, especially for staff because we are on top of each other, getting on each other’s nerves. When we are spaced out like we are now, it makes life a whole lot easier for everyone. It is running really well,” she concludes.

Ambitions

Completing our visit and speaking briefly on ambitions for his time as Governor of Limerick Female Prison, McCarthy provides a succinct response. “The simple answer is empty beds,” he insists. “If the same people are not coming back time and time again, that means we are doing our job.”

Indicating that he wishes to continue the work he has undertaken, expanding on the courses being made available to prisoners, he concludes: “I want to make Limerick Female Prison a university of life rather than a university of crime. That might sound clichéd but that is what we are trying to do here.

“You and I cannot fathom the chaotic lives these women have lived. I work with them every day and I still cannot get my head around some of the trauma that they have to deal with. Maybe it is a reflection on society. It is sad and you do feel sorry for many of them, but we just have to do our job and get on with it as best we can.”

*The names of the female life sentence prisoners have been changed.