‘Invisible’ cuts impact rankings

Universities have once again called for the State to provide additional resources following a decline in their world ranking standings but no action is expected until at least mid 2020.

An almost 50 place fall by Ireland’s top rated university in the world ranking standings has brought fresh pressure on the Government to resolve the need for a clear policy on the future funding of Ireland’s higher education sector.

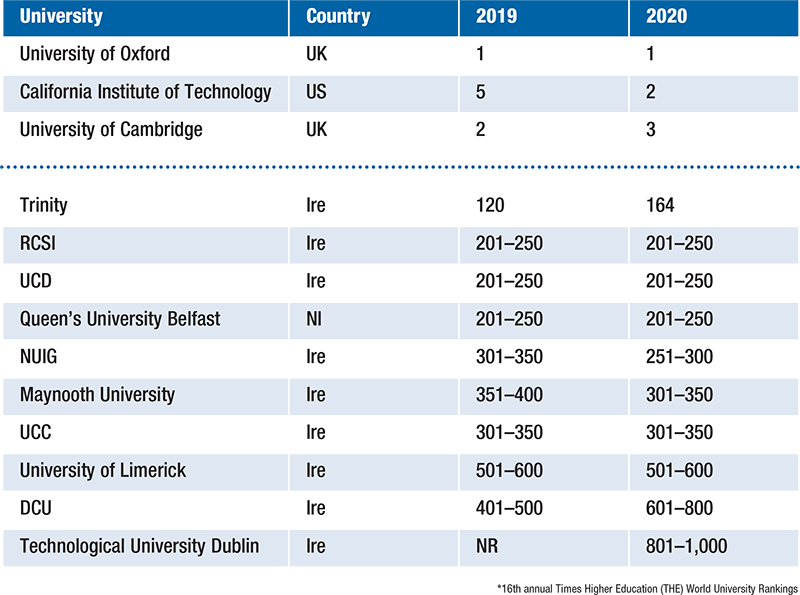

Times Higher Education rankings, which less than 10 years ago listed Trinity College Dublin and University College Dublin in the top 100 of its world university rankings, have moved Trinity down some 40 places to 164th place.

The drop marks an almost decade long decline in the reputations of Irish universities when compared to their counterparts and has been largely attributed to government underfunding in the sector.

The Times ranking, which places universities outside of the top 200 in bands of 50 or more, placed the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and UCD in the 201st–250th category. Both NUI Galway (251–300) and Maynooth University (301–350) moved up a rating bracket, while University College Cork (301–350), University of Limerick (501–600) and Technological University Dublin (801–1,000) retained their places.

Dublin City University fell in this year’s rankings from 401–500 to 601–800.

In 2018, Peter Cassells authored a report that set out three options for the future funding of Ireland’s higher education sector. Last year, the Government avoided taking a decision on policy by asking the EU to carry out an evaluation. An outcome is not expected until close to the end of 2020.

Cassell’s three options centred on: a state-funded system; increasing government expenditure in the sector; or an income-contingent loan system.

The EU’s Structural Reform Support Service has awarded the contract for the evaluation to a consortium, including a Dublin-based financial management consultant company. However, terms of reference for the consortium are broader than the Cassell’s recommendations and include balancing higher education funding with other options such as education and apprenticeships.

Austerity cuts to third level institutions following the financial crash have not been reversed despite strong evidence that university incomes are largely linked to their position in global rankings. It’s estimated that daily running costs in Irish institutions are some 43 per cent below 2010 levels.

The issue is long-standing, in 2016 the President of UCD and the Provost of Trinity felt compelled to issue a joint statement calling on the Government to address the “funding crisis” in higher education following a fall for both universities in the QS World University Rankings.

The pair pointed to the impact of decline in standings on investors, employers, prospective international students, academics and research and warned about the impact rising student numbers was having on student/staff ratios, a factor identified by the OECD in 2018 which found that Ireland was one of a small group of developed countries to have student-teacher ratios of more than 20 to one in third level.

“As a small open economy which is heavily dependent on FDI and on the employment of highly educated staff, we cannot afford to fall behind our competitor countries in terms of investment in higher education,” they said.

The most recent decline is also worrying in the context of Ireland’s long-term development plans. The National Development Plan and the National Planning Framework have raised questions around whether Ireland will retain the skill capability necessary to deliver on its ambitious plans.

In June, the QS World University Rankings painted a similar picture to those which have emerged from the Times Higher Education rankings. Trinity slipped further out of the top 100, down four places to 108th. However, UCD improved in stature, climbing eight places to 185th. NUI Galway (259) and UCC (310) both improved, while DCU (429) and University of Limerick (524) fell slightly. Both Maynooth University (724) and Technological University Dublin (788) remained in their previous positions.

The Department of Education has pointed to a 25 per cent increase in funding for the third-level since 2015, with further commitments under the ‘human capital initiative’, however critics say that the investment is not additional and is being used to meet rising student numbers and public sector pay increases.

Speaking to the Irish Times, Trinity’s Dean of Research, Linda Doyle said that while the college’s performance was steady, this was not good enough in a world where competitors are benefitting from sustained investment by their governments.

“There is no denying that continuing underinvestment in university education and research in Ireland is catching up with us,” she said.