Ireland 2040: Will it be implemented, and does it go far enough?

12 months on from the publication of Ireland 2040, we are in a slightly better position now to assess the two key questions surrounding the National Development Plan (NDP); Labour Party candidate in the upcoming local elections and SIPTU head of policy and equality Marie Sherlock asks: will it be implemented, and does it go far enough?

Despite the fanfare surrounding the stock of capital spending within the NDP of €116 billion, the flow of additional financial commitment in Ireland 2040 is relatively modest. Only €4.3 billion in additional cumulative exchequer spending is planned over the decade 2019-2027. This comes in a period where the current government is forecasting exchequer surpluses of up to €12.7 billion between 2020-2023.

Notwithstanding the considerable risks that do arise, and which will we get them anon, there seems a high probability that the money allocated to the NDP will get spent.

What is much less certain is the extent to which the 10-year spending plan can actually deliver on the goals of the Ireland 2040’s National Planning Framework (NPF).

Unlike previous capital plans and national spatial strategies, the 20-year spatial plan for the country; the National Planning Framework (NPF) was developed in tandem with a 10-year capital investment plan. Despite this major innovation in policy making, a gap remains between the ambition of the NPF and the funding and incentives provided for under the NDP. Arguably, housing and climate change action are the two clearest examples of this gap.

We are told that resolving the issues driving the current housing crisis lies at the heart of the plan. Yet the patchy detail in the plan nor the funding allocation for these initiatives nor the scale of housing envisaged convince that the plan can overcome the housing crisis.

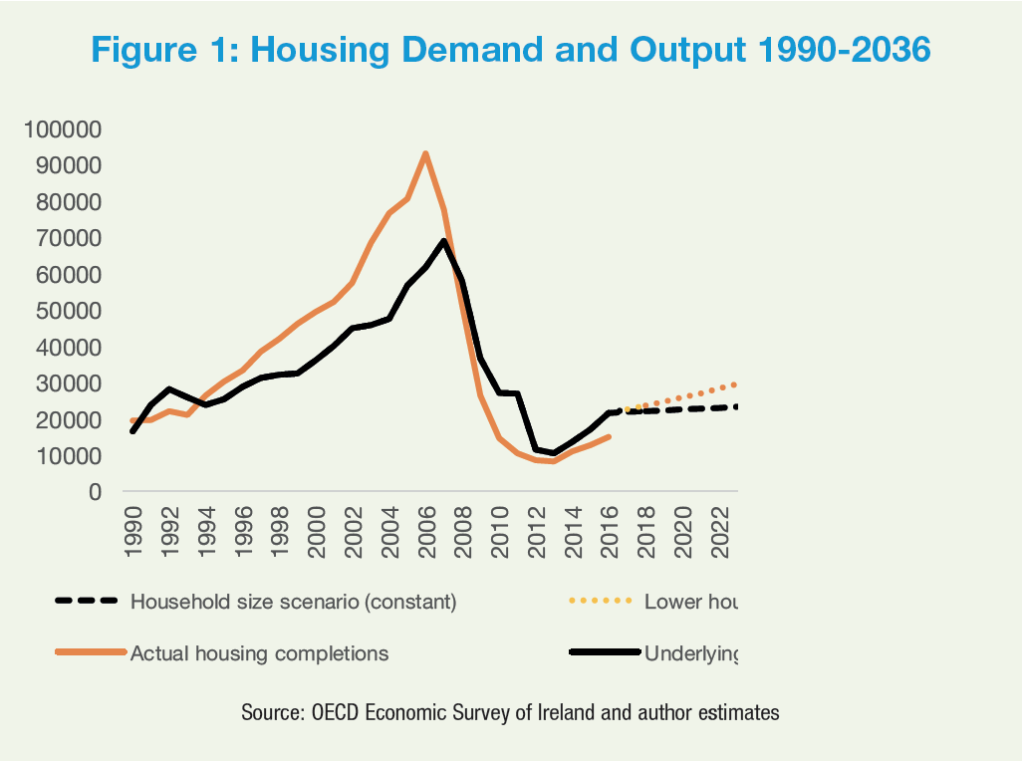

Twelve months on from NDP publication, we haven’t seen any significant additional detail to persuade that up to 35,000 housing units can be built by the private and public sector each year to meet future housing need over the next decade.

Provision is made in the NDP for the extension of the Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund (LIHAF) and the Urban Regeneration and Development fund to assist the development of private housing but these initiatives are expected to support the construction of just under 26,000 houses over the period of the plan, a figure that falls far short of the annual target.

The National Planning Framework identifies a need to deliver 550,000 houses between 2018 and 2040, with some 25,000 new houses required per annum to 2020 and somewhere between 30,000 to 35,000 houses each year to 2027.

Alternative analysis suggests a figure closer to 50,000 houses is required on an annual basis.

The chief factor behind this relates to estimates of housing formation. Ireland 2040 assumes average household size to marginally decline between 2018 and 2040. If the household formation size were to fall in line with the long term trend 1988-2016, then the housing requirement significantly rises.

Ultimately, it seems that the implementation of the 10-year funding plan will depend on the degree to which three key risks are realised; political, labour supply and operational.

Almost 60 per cent of the total NDP spend has been backloaded to the period 2023-2027. This happens to coincide with the early years of any new political and economic arrangement between the UK and the EU and by extension, the Republic of Ireland. As we write, the final outcome of Brexit remains unclear. Yet we are already seeing its impact on government spending decisions. The cost overrun in the National Children’s Hospital project combined with uncertainty about Brexit means the Government have already moved to delay funding other major health projects.

While capital expenditure will account for just over 11 per cent of gross voted government expenditure some five years into the NDP in 2023, there are concerns that the capital spending plan will become vulnerable in the event of a downturn. It has been signalled by government that all exchequer financed capital expenditure will be funded from within own resources from 2019 so in the event of a downturn there will be no guarantee of outlay for the NDP.

Construction labour shortages have been held up as a concern for delay in the implementation of the NDP. Given that 60 per cent of the NDP outlay is planned for post 2023, if private sector housing activity ramps up to the scale required around that same time, then there may be an escalation of labour supply shortages around that period. Furthermore, SIPTU analysis of working conditions in the sector suggests future difficulties in recruitment. On the ground, SIPTU members report that alternative employment opportunities that offer lower work intensity and more consistent and secure employment is crowding out labour supply into the construction sector.

In terms of operational challenges, unfortunately, no profile of additional current expenditure required to operate new capital projects has been made available. This poses a serious issue for the profiling of public finances into the future.

With the exception of the revised Common Appraisals Framework within the Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport along with projects covered by PPPs and Irish Water, it is not clear whether ongoing operational costs are assessed a priori in any other public funding costing and where it is included in the calculation, no standard methodology exists across departments and agencies.

In the event of downturn in the public finances, failure to factor in the associated operational and maintenances costs of a piece of infrastructure.

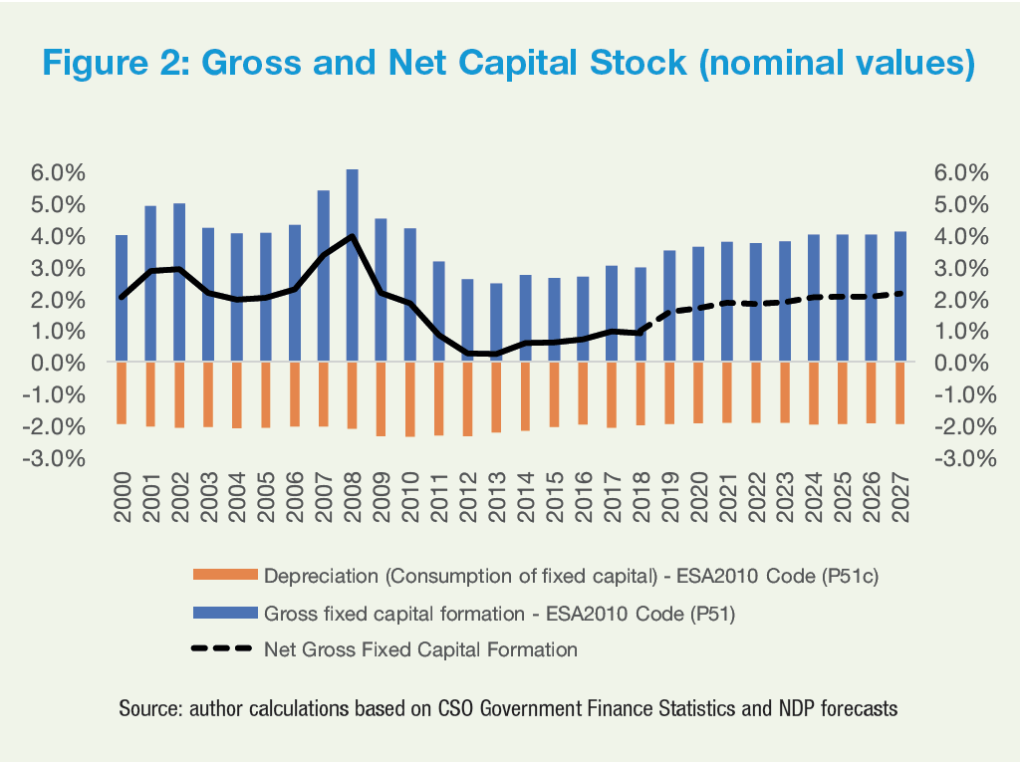

Finally, an integral part in the assessment of any spending plan is to identify its additionality. Such is the obsession with new infrastructure in Ireland that it is appears that little attention is given to the concept of upgrading and maintaining existing capital stock.

Estimates produced by IFAC in 2016 on capital expenditure during the worse years of the economic and financial crisis suggested that net new additions to the capital stock during that period were close to zero. Our estimates suggest that the actual net new capital stock will grow at less than half the rate of public investment over the period 2018-2027.

In that context, the NDP is likely to have much less of a dramatic impact on the expansion of public infrastructure over the next decade, than might otherwise appear.

This article is an edited version of a more detailed paper produced at the PPAN seminar, in 22 October 2018.