Ireland’s EU referendums

A poll on a fiscal treaty would be the ninth EU-related referendum in Ireland. Stephen Dineen looks at the electorate’s track record.

The Government’s reluctance to hold a referendum on an EU fiscal compact is not surprising. Regardless of the amount of time, energy and cost involved, Ireland’s relationship with the EU at the polling booth has become complicated.

UCD political scientist Professor Richard Sinnott, an expert on Ireland’s voting behaviour in EU referendums, told eolas he believes any forthcoming EU referendum will differ from previous ones. The Irish referendum experience has been one of a country being the recipient of EU largesse “whereas in the upcoming one Ireland will be a recipient, or certainly be seen by some voters and campaigners, as a recipient of pain rather than largesse.” This will make it more difficult for the Government to win, “but it will also simplify the issues, because I think the issues will focus around that particular problem.”

Ireland’s early EU-related referendums were passed with strong majorities. Accession to the European Community was ratified 83:17 in 1972, and referendums on both the Single European Act (1987) and the Maastricht Treaty (1992) were passed comfortably. The Amsterdam Treaty referendum, held in 1998, was the first time that less than two-thirds of voters endorsed EU treaty change.

The political establishment was stunned in 2001 when the Nice Treaty was rejected. On a turnout of 35 per cent, the ‘No’ side had a majority of 76,000 votes (54:46). Research conducted after the referendum showed that the ‘No’ side won in part because of the low turnout and not any major shift in opinion about Ireland’s place in the EU. The anti-treaty camp included those dissatisfied with the EU policy-making processes, supportive of strengthening Irish neutrality and opposed to enlargement. Some voters were mobilised to choose on the basis of perceived implications for divisive policies such as abortion, with the ‘No’ side benefiting most. Older people and women were more likely to vote ‘No’. Late decision-making, particularly among eventual ‘No’ voters, was also a feature.

When the referendum was re-run in 2002, a large majority accepted the treaty (63:37). Despite a turnout of less than 50 per cent, the increase from 35 per cent to 49 per cent was explained, according to subsequent analysis, by greater enthusiasm for integration. The generational and gender effects on voting were absent and there was increased understanding of the treaty. The number of voters who claimed to have understood at least some of the issues involved rose from 36 per cent in 2001 to 61 per cent in 2002.

The Lisbon Treaty was the second treaty to be rejected, with 53 per cent voting ‘No’ in June 2008 on a turnout of 53 per cent (significantly higher than the first Nice Treaty referendum). Analysis of the result conducted for the Department of Foreign Affairs (by academics Sinnott, Elkink, O’Rourke and McBride) found that the outcome was determined by overall attitudes to EU integration, knowledge levels regarding the EU, incorrect perceptions of the treaty’s contents (about conscription, abortion and control of the corporation tax rate), disapproval of the loss of a permanent Commissioner, and domestic political factors.

Many who abstained cited low levels of understanding or lack of information, while the ‘No’ vote was composed of those with concerns about the EU’s position on wage rates, low levels of knowledge about the treaty, people opposed to the scope of EU decision-making and a rotating commissionership. The higher a person’s labour skill set, the less likely they were to vote ‘No’. People with more positive attitudes towards the EU voted ‘Yes’. Analysis also showed that satisfaction with the Government is neither necessary nor sufficient for winning such a poll.

Fifty-nine per cent of the electorate voted in October 2009 in the second Lisbon Treaty referendum, in a very different campaign. The ‘Yes’ camp retained nearly all its voters from the first vote, a quarter of previous ‘No’ voters switched and one-sixth of those who had abstained in 2008 voted ‘Yes’. The extensive unpopularity of the then government had only a limited effect.

Among those who were more likely to vote ‘Yes’ were those in upper middle class occupations, while the ‘No’ vote was characterised by those in lower middle class, skilled and unskilled working class occupations and small farmers. Sinnott and Johan A Elkink found that the outcome boiled down to people’s attitude on whether Irish membership of the EU was a good thing and whether a ‘Yes’ vote would result in improved economic prospects. Assurances that the country would have a permanent Commissioner and control of taxation also contributed.

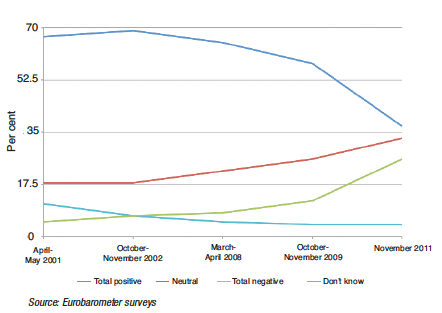

Public opinion and socio-economic conditions have changed considerably since the first Nice Treaty referendum in 2001 and also the second Lisbon Treaty poll in 2009. Eurobarometer polling, which has been conducted in member states since 1973, shows public opinion towards the EU has soured in a country that has traditionally had high satisfaction levels with membership.

Trust in the EU has halved since the time Ireland accepted the Lisbon Treaty (from 47 per cent to 24 per cent), with distrust increasing from 35 per cent to 60 per cent. In November 2011, only 34 per cent of the Irish public felt that the interests of Ireland were well taken into account by the EU, with 54 per cent disagreeing. The gap between those who see the EU as a positive thing and those who see it negatively has narrowed from 46 per cent in the autumn of 2009 to 11 per cent at present (see chart).

Sinnott believes a referendum on the fiscal compact should not be held on the same day as that on children’s rights or abolition of the Seanad. He believes such polls, particularly concerning children, could become quite fraught “depending on how the sides line up and what the Government wording of the referendum is,” and the airwaves could be “taken over” by that debate.

Referendum results (%)

| Turnout | Yes | No | |

| Accession to the European Communities (May 1972) | 71 | 83 | 17 |

| Single European Act (May 1978) | 44 | 70 | 30 |

| Maastricht Treaty (June 1992) | 57 | 69 | 31 |

| Amsterdam Treaty (May 1998) | 56 | 62 | 38 |

| Nice Treaty I (June 2001) | 35 | 46 | 54 |

| Nice Treaty II (October 2002) | 49 | 63 | 37 |

| Lisbon Treaty I (June 2008) | 53 | 47 | 53 |

| Lisbon Treaty II (October 2009) | 59 | 67 | 33 |

Ireland’s image of the EU