Looming tariffs could expose Ireland’s reliance on tax receipts

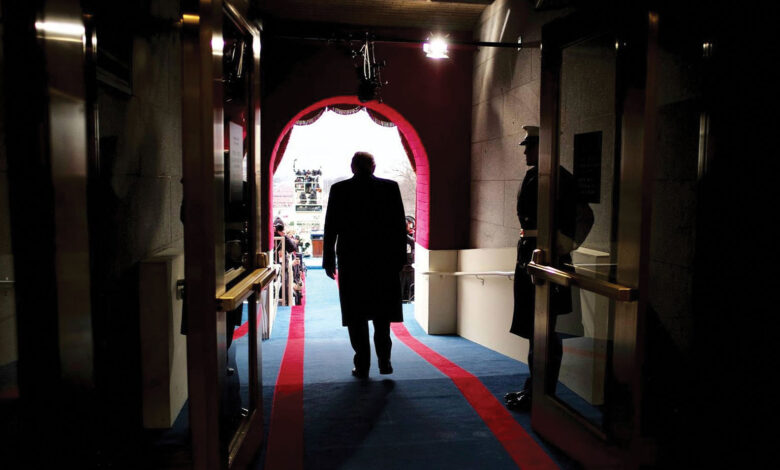

President-elect Donald Trump’s impending return to the White House on 20 January 2025 will put Ireland’s public finances at significant risk, should the 47th president deliver on his pre-election promises, writes Matthew O’Hara.

Trump has pledged to incentivise industries to bring production back to the United States, and to slash the corporate tax rate close to Irish levels (12.5 per cent). His policy of economic nationalism ‘America first’, could prove challenging to the incoming Irish Government, as Ireland’s long reliance on a low corporate tax rates has foreign direct investment (FDI) from US multinationals.

Weeks prior to Ireland’s general election 2024, Taoiseach Simon Harris TD warned that Trump’s return to the US presidency would send an “economic shock” to Ireland’s economy, and said before the general election that he was setting aside “significant funds”, to protect the country from potential tariffs.

Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin TD, whose party returned the most seats to Dáil Éireann, emphasised the need for all parties to move in a timely manner to discuss formation of government because of “pressing issues internationally”. He cited in particular, the inauguration of Trump in January 2025 and asserted that his return to the White House imposed “an effective deadline” on Ireland’s own government formation challenge.

There is consensus amongst Martin and Harris on the form a new government in time for 20 January 2025, Trump’s inauguration date.

Fears will only be compounded by a recent post on X by Howard Lutnick, the billionaire Chief Executive of Cantor Fitzgerald and Trump’s pick for Commerce Secretary which states: “It is nonsense that Ireland of all places runs a trade surplus at our expense. We do not make anything anymore. Even great American cars are made in Mexico. When we end this nonsense, America will truly be a great country again. You will be shocked.”

Ireland and US corporations

Ireland’s corporate tax income is expected to total €37.5 billion at the end of 2024, with American companies employing over 200,000 people in the State, and supporting 167,000 jobs indirectly, making Ireland America’s gateway into Europe.

Broadly speaking, corporation tax now accounts for 25 per cent of total tax revenue in Ireland, with just three big US companies accounting for nearly one in every eight euros of total tax collected in Ireland.

One of Trump’s key promises is a blanket 10 to 20 per cent tariff on imports and a lowering of the US corporation tax, currently at 21 per cent – the rate would be 15 per cent for companies that produce domestically in the US.

Over 1,000 US companies currently contribute to Ireland’s GDP, accounting for 13 per cent of the State’s GDP. There are fears amongst Irish and European leaders, that the more favourable the tax conditions and harsh trade tariffs are, could ultimately turn some of the FDI away.

A study undertaken by the Danish Industry Federation using a model developed by Oxford Economics estimated that 30,000 jobs in Ireland could be at risk in a “worst-case scenario”.

According to research professor at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Kiernan McQuinn, Trump’s re-election brings “considerable uncertainty”, to Ireland’s economic outlook and points out that if Trump’s policies are implemented, they “pose a threat to the traded sector of the economy, jobs and these revenues”.

Moreover, chief economist at the Institute of European Affairs, Dan O’Brien, went as far as calling the potential tariff on all goods shipped to the US the “biggest near-term risk” to the Irish (and European) economy.

What can we expect for future US-Ireland diplomatic relations?

After Trump’s inauguration, the attention of Ireland’s political and business leaders will turn to St Patrick’s Day in Washington, the key diplomatic event on the Irish political calendar ever since the Eisenhower administration.

With a second Trump term, the political and diplomatic challenges for Ireland’s leadership will be to cultivate as close a relationship as possible with the incoming administration in order to advance Irish interests, while also walking a tightrope whereby they do not jeopardise existing relationships within the EU or compromising Irish foreign policy principles.

Former Irish ambassador to the US Dan Mulhall states that establishing relationships with the Trump team will be an immediate priority. “Every EU country has the same challenge, how to relate to Trump and his team,” he says.

In Trump’s first administration, there was a significant cohort of Irish Americans around Trump, several of whom smoothed the way for communication between Dublin and the White House.

Indeed, some Irish-American names have been suggested for Trump’s new cabinet. According to Ted Smyth, a former Irish diplomat who went on to work in corporate America and has connections amongst Irish-political networks, the names touted for the inner circle around Trump include Robert O’Brien and Senator Bill Hagerty, although it is unclear if they will play a role in the new administration given that Trump has already put forward several nominations for cabinet positions which are pending US Senate approval.

However, attempting to cosy up to Trump’s administration is not without political dangers, especially if the US pursues policies which are unpopular and damaging to the EU’s and, in turn, Ireland’s interests.

Consensus amongst most political commentators is that former Taoisigh, including Enda Kenny and Leo Varadkar, pulled off a reasonably successful balancing act in asserting EU-Irish principles while maintaining good favour with President-elect Trump.

Moreover, should Trump impose tariffs, Ireland is currently in “a good position economically”, with significant buffers built up in cash balances, ongoing budget surpluses and the Government’s saving funds, according to a series of consultations, led by the Secretary General of the Department of Taoiseach John Callinan. He also notes that Ireland will have to work “intensively” with EU partners to mitigate potential downsides.

While a second Trump presidency creates uncertainty for Ireland’s economy and politicians, similar projections were made about the severe impact an ‘America first’ economic isolationist policy would have in the Irish economy – but prior to Covid-19, US-Irish relations remained largely the same.

Mulhall has echoed that Trump “has a certain regard for Ireland”, adding that “he has the connection with Doonbeg, that’s a very positive thing”, a reference to the Trump-owned golf resort in County Clare.

“I take the view that this is a very challenging moment for Ireland and the EU, but we should not work ourselves into a fit of despair. We will find a way to cope,” Mulhall asserted.