Northern economy at a ‘disadvantage’ in attracting multinational activity

Despite similar growth rates, a consistent 25 per cent gap in economic activity exists between both economies on the island says Department of Finance.

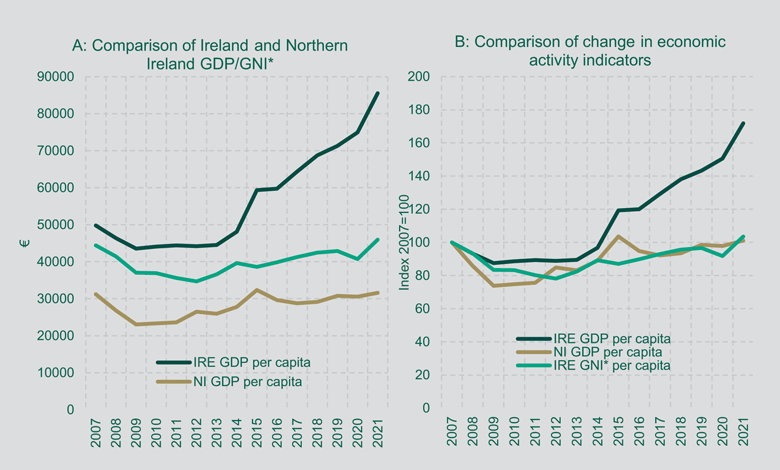

The identification of the large gap between GNI* per capita in the Republic and GDP per capita for the North is included in analysis carried out by the Department of Finance to explore the similarities and differences in economic structures between north and south.

Other key findings include a large qualification and higher education gap, higher comparative public spending in Ireland on health, education, and housing, as well as a lower labour force participation rate in Northern Ireland.

The analysis was carried out in the context of the Government’s Shared Island Fund’s commitment to at least €1 billion up to 2030 of cross-border investment, and seeks to examine the similarities and differences in economic structures in Ireland and Northern Ireland, as well as cross-border flows of trade, tourism, and commuting patterns.

The Republic’s GDP figure is recognisably distorted due to the inclusion of multinational activity and therefore often not used for comparison. Instead adjusted gross national income (GNI*) is the preferred indicator of the performance of Ireland’s domestic economy. When scaled by population for comparability, the Republic’s economic activity is estimated to be some 25 per cent greater than that of Northern Ireland.

This growth is underpinned by evident differences in the levels of post-financial crash growth. Between 2007 and 2021, Gross Value Added (GVA) per worker had barely increased in Northern Ireland when inflation is taken into consideration, whereas the Republic has witnessed accelerated growth since 2015. A “growing gap in the performance levels of the two economies, with Ireland increasingly outperforming Northern Ireland”, highlighted by GVA comparison is not as evident when multinational data is excluded in the Republic. However, productivity is still higher in Ireland relative to Northern Ireland using this measure.

Another significant difference in both economies relates to trends in the labour market. Northern Ireland and the Republic display a similar share of the total working-age population who were either in employment or actively seeking employment until the Covid-19 pandemic broke. The Republic’s labour force participation is tracked as having dropped briefly before rebounding strongly and rising to levels similar to pre-Celtic Tiger highs in 2008. In contrast, the North’s labour force participation was not hit as hard (aided by the UK Government’s furlough scheme and higher levels of public sector employment), but has not experienced the same recent increase in participation.

“This has resulted in a reasonably substantial gap in labour force participation opening since 2021,” the report states. Further analysis of this gap suggests that the North has a higher prevalence of disability and limiting health conditions amongst the population.

Focusing specifically on skills, the North has a much greater proportion of its population with no qualifications, a characteristic particularly evident in the oldest age category.

“Across the different age categories, Northern Ireland consistently has a higher proportion of its population than Ireland for whom finishing secondary school is the highest level of their educational achievement. The picture is the reverse when it comes to third level education with a consistently greater proportion of the working age Irish population achieving this level of education compared with their Northern Irish peers.”

Fiscal balance

Acknowledging the very different public finance structures in the two economies, the Department of Finance analysis surmises that the Republic’s income tax system is “more progressive”, ensuring that individuals on lower incomes take home more of their pre-tax income than those in the North, with the reverse occurring for those on higher incomes.

The North’s per-person public spending is higher than the Republic’s on social welfare, however, spending per person in the Republic is higher in the key areas of health, education, and housing.

Trade

Interestingly, in assessing the openness of both economies by comparing trade flows, the report estimates the North is about half as open as the Republic. The Republic’s trade (exports plus imports) is equivalent to twice the country’s total GDP, whereas, in the North, external sales and purchases (including to Great Britain) are similar to total GDP. Use of a stricter definition of international trade – excluding trade flows with Great Britain – sees the North’s openness further halved.

Trade flows from the North to the Republic are consistently higher than the opposite direction, most likely driven by Ireland’s connectedness to further markets for export and also because the Republic’s multinationals are a crucial driver. Trade flows between the two economies had displayed moderate growth between 2011 to 2020, but have risen sharply by some 30 per cent post-Brexit. Cross-border trade is broadly dispersed across sectors, however, both economies share a similarity in their international exports, with the chemicals and pharmaceuticals sector and the machinery and electrical equipment sector, dominating.

Alongside trade flows, cross-border connections in terms of commuter flows and household visits are also telling. Higher number of workers travel from the North to the Republic for work, than vice versa, driven by greater labour market opportunities and higher wages in the South.

Concluding, the Department’s report highlights that the greatest divergence in aggregate economic performance is defined by the inclusion of the large multinational sector in the Republic.

“Attractiveness to multinational activity is an area where Northern Ireland is at a disadvantage relative to Ireland with lower levels of educational attainment amongst the working age population alongside a higher tax rate on corporate profits,” it states.

However, the report acknowledges that the special trade status of Northern Ireland under the Protocol to the Withdrawal Agreement has had an impact on the expansion of cross-border trade, and suggests potential in this area for further development of linkages to increase economic outcomes on both sides of the border.