Not working: Where have all the good jobs gone?

Labour economist and author David Blanchflower discusses how unemployment figures are becoming less important to wage growth and economic performance, believing underemployment to be the best and most accurate measure.

David Blanchflower, an economics professor at Dartmouth College and a former external member of the Bank of England’s interest rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), says that despite claims that many leading economies are at or reaching full employment, labour market slack is behind weak inflation and low wage growth.

Blanchflower believes that current forecasts of weak growth for many economies, such as Ireland’s and the UK’s, are too optimistic and bases his assumption on the fact that many economic forecasters appear not to have learned from errors of the past.

Defining these errors, Blanchflower focusses on the UK and points out that in 2008-09 central bankers missed the emergence of the recession and had still not recognised it nine months after it had started. “It wasn’t that they didn’t have any foresight, they didn’t actually have any hindsight and that raises a problem when considering the current economic outlook,” he says.

Another error, he believes, was the implementation of austerity, which he describes as an “unmitigated, reckless disaster” and which he says explains much of today’s fractured political and economic outlook, including Brexit.

“It looks to me that the mistakes that were made in 2008 are being repeated now and there is every prospect that the UK is already in recession,” he states.

Offering context to his argument, Blanchflower highlights that while some may believe that UK policy post-recession has been successful, the reality is that the recovery from the 2008 crash in the UK is the third slowest recovery ever, behind only the South Sea Bubble in 1720 and the Black Death 600 years ago.

Blanchflower points to the assumption that existing low unemployment levels means economic prosperity, recognising that the labour market has often been the major gauge of economic prosperity and that reaching full employment (3 per cent of the total labour force idle at any time) is often associated with economic boom.

In response, he poses the question: “If the UK and US are at full employment, how come so many people are hurting?”

The labour economist believes that much is do with overly optimistic forecasts. Using the example of the Bank of England’s August 2008 GDP projection based on market interest rate expectations, which projected no recession, despite the fact that EU economies had actually been in recession for about six months and the US’s longer still, Blanchflower highlights the UK GDP estimate for Q2 of 2008 as +0.2.

“That completely threw me, I had been saying the UK was in recession,” he admits.

“Actually, what happened was that the estimate didn’t get revised down to a negative until July 2009 and so you’d have to wait until then to recognise two successive quarters of negative growth in the data. What was first estimated as +0.2 growth actually became -0.7 growth and what turns out to be true is that the original estimates were horribly wrong because policy makers and statistical analysts are much too optimistic.

“The reason this is so relevant is because I think this is probably where we are currently and the figures are overly optimistic.”

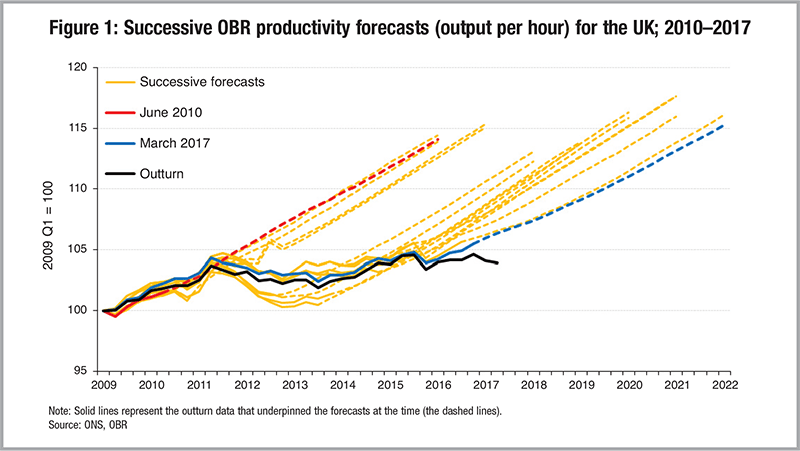

Turning to the period after the recession, he points out that the original OBR productivity forecasts for 2010–2017 and the subsequent 20 forecasts, based on outturn data, were far more optimistic than the eventual outcome (see figure 1).

Blanchflower believes that forecasting optimism is also diagnosable in the labour market.

“Despite the fact that output doesn’t pick-up and productivity doesn’t rise, you still keep saying it’s all going to be fantastic and it never turns out that way. You also say wage growth has been really weak but don’t worry, wages are all going to pick up because we’re nearly at full employment.”

Pointing to 23 successive MPC wage forecasts for the period 2014–20, Blanchflower highlights how “optimistic” forecasts have constantly been revised down. Taking 2015 as an example, the original forecast made in 2014 for 2015 was a 3.75 per cent increase in wage growth. The subsequent revisions were Q2: 3.5 per cent; Q3: 3.25 per cent; and Q4: 3.25 per cent. However, the outcome was much lower at 2.4 per cent. This is a similar story throughout the forecasts.

“What you see each time is that the same forecast is always being made despite the evidence to show that these were wrong 22 times.”

Blanchflower outlines that despite a pick up in wage growth in the UK and the US over recent years, wage growth has done nothing like what forecasters have predicted. Diagnosing this, he adds: “The assumption was that wage growth would mean revert and go back to 2008 levels, meaning wage growth in the order of 4–4.5 per cent. This is the forecast that has always been made but wage growth has not mean reverted.”

So why is the wage growth so weak? Blanchflower outlines that real wages in the UK are some 4.5 per cent below what they were in 2008 and that real wages are much less than they were for the same period, something which should not be the case if the UK was at full employment.

“Wage growth is expected to slow in the year ahead, according to the latest research from pay analysts XpertHR”, he says. “Pay awards over the past year have typically been worth 2.5 per cent but there is less optimism for the coming year, with a going rate of 2.1 per cent expected to emerge over the next 12 months, much less that the AWE Total Pay single month growth which averaged at 3.5 per cent but had many exclusions.

“Similar data in 2008 suggested that we were in recession and it appears to me that at the very least growth is going to be very weak.”

Underemployment

Blanchflower previously authored the book ‘The Wage Curve’ which looked at how the unemployment rate impacted wages and prior to 2008, the unemployment rate kept wages down because of the availability of other workers.

“It turns out that post-2008 my wage curve book is wrong,” he states. “The unemployment rate is now irrelevant for wage determination and what matters is the underemployment rate.

“If you want to explain the fact that a variable has not mean reverted you need to explain it with a variable that has also not mean reverted and so the new labour market variable is the underemployment rate.”

He adds: “It appears that instead of wages being impacted by things at the external margins, ie the labour market, they are now actually being impacted at the internal margin.

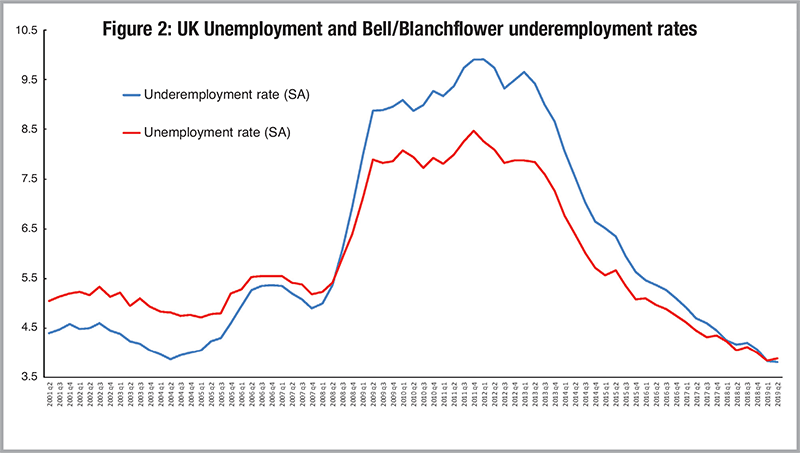

Blanchflower defines underemployment as a worker who carries out a set number of hours but would like to work more hours, believing these underemployed staff are inadvertently keeping the wages of those working their desired hours down.

“When recession hit in most countries the number people who said they wanted more hours, rose sharply and there was a fall in the number of hours that full-timers wanted their hours reduced by. Even though the unemployment rate has returned to its pre-recession levels in many advanced countries, underemployment in most has not.

“Underemployment replaces unemployment as the main influence on wages in the years since the great recession and this largely explains the lack of wage pressure and why central banks have been wrong.”

Blanchflower believes that a misunderstanding of labour markets is driving mistakes in economic growth predictions and that even though unemployment rates are at historic lows in many countries, this does still not suggest that those country’s labour markets are close to full employment.

“Underemployment replaces unemployment as the main measure of labour market slack in the post-recession years,” he states.

Blanchflower believes that a greater focus on business sentiment could be more valuable in assessing wage growth predictions than the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), which was over-estimated by central banks when wrongly raising rates. Taking the UK’s 2008 experience as an example, he points to various business surveys such as the Bank of England’s agents’ scores, an EU’s Commission sectoral survey of the UK and consumer perceptions which all show declines at a time when the recession had not yet been identified.

The academic draws comparisons with similar data occurring now of a steady decline of similar scores. “We’re now in a territory for many businesses that we haven’t been in since 2008. When this happened in 2008 it predicted that was coming was going to be horrible and that is a concern.

He concludes: “The phenomenon is that we have seen error upon error despite clear signs that structural change has occurred. There is a clear desire to seek business as usual but that is no longer where we are. I don’t think we’re at full employment and I think the NAIRU is likely to be untrue. If we were at full employment then wage growth would be taking off and it’s not.

“As it turns out, underemployment proves to be the most important variable and that’s an explanation to why people are hurting and why I think recessions are coming.”