Opinion polls through the crisis

Michael Marsh explains how the polls show a severe drop in support for Fianna Fáil after each unpopular financial decision.

In 2002 and again in 2007, the evidence from opinion polls and focus groups led Fianna Fáil strategists to follow James Carville’s advice and emphasise the economy in the election campaign, while that same evidence persuaded the Fine Gael handlers to avoid that topic. Fianna Fáil was going to be the clear winner if the contest came down to who was most competent to sustain the dream, or at least allow us to awaken gently.

In 2011, following a most rude awakening, the dream was well and truly over. The RTÉ-Lansdowne exit poll, and those carried out during the campaign indicated what is probably an unprecedented level of uncertainty among voters in 2011, but that uncertainty conceals a resolve that most voters made quite some time ago: they would not vote for Fianna Fáil. Many polls showed that the voters were very angry, and it is surely obvious that they have been angry for some time. Voters in last month’s election manifested a resemblance to Jane Austin’s Mr Darcy, who found it hard to forgive offences against him and in consequence his good opinion, once lost, was lost forever. Their faith in Fianna Fáil’s competence was withdrawn, perhaps permanently.

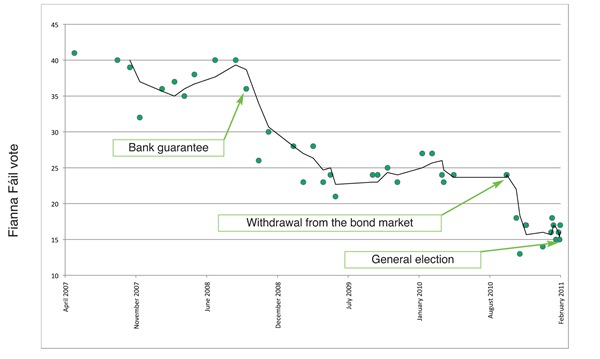

To understand why that party won only 17 per cent of the vote, having collected 41 per cent in 2002 and 2007, analysis has to start with two of the defining episodes of the Fianna Fáil led coalition. The first was the ill-fated bank guarantee of September 2008, and the second was the withdrawal from the bond markets at the end of September 2010 and the admission that the adjustment that would be required in the December 2010 Budget was close to twice what the voters had previously been led to expect.

The graph, which is based on all Red C polls from the 2007 election onwards (and includes the 2007 result) shows the dramatic fall in support for Fianna Fáil at each of these two points. Together, these two episodes account for almost all of the 24 percentage point decline in that party’s vote. There is no sign of support either rising or falling significantly between late September 2008 and September 2010, nor after late September 2010, apart from the sudden drop on both of those occasions.

There was no steady accumulation of discontent culminating in a final decision to vote for someone else. Good months were followed by bad months, as support fluctuated as if randomly around a new level established quickly after each crisis. Remarkably perhaps, even the (loudly denied) visit by the ECB-IMF ‘bail-out’ team had no effect. The party was down below 20 per cent and there it stayed.

One might say that the Fianna Fáil goose was thoroughly cooked five months before the election. The only question that remained was who would eat it.

There is not the space to show graphs for other parties here, but Fine Gael’s is initially the mirror image of that for Fianna Fáil, rising sharply immediately after the initial bank guarantee and then remaining stable. Only in the last six months does it diverge from the mirror image, support growing steadily rather than in a sudden movement. Perhaps too the rise is better linked to the arrival of the IMF rather than withdrawal from the bond markets. Labour’s trajectory is different again, though it too shows a sudden step up in September 2008. This was followed by a gradual rise culminating last autumn, and a decline that also seems to follow the bail-out. Finally, the rest: there the increase is almost all very recent, with growth following the news of our ‘loan facility’ last November.