Oversight and accountability now key to climate action

Independent Report Card on Government progress must be complemented by robust parliamentary scrutiny, according to Friends of the Earth Chief Executive, Oisín Coghlan.

Friends of the Earth recently published its third annual independent assessment of how well the Government is doing at fulfilling the climate and environmental commitments adopted in the 2020 Programme for Government. It was the most ambitious ever on climate action in particular but of that is of little value if it is not followed up with implementation and impact.

So how is the Government doing as judged against its own promises? Researchers from UCD compiled information on the nearly 300 climate and environmental commitments in the Programme for Government, from documentary sources and through 43 interviews with official and civil society stakeholders. The resulting 81-page compendium was used as the basis for scoring progress across nine categories by three academic experts from UCD, UCC and DCU.

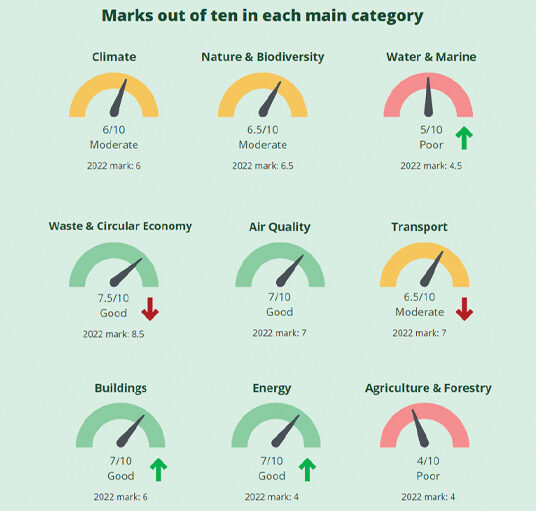

Overall, in 2023, the Government received a C+ grade for moderate progress, a small improvement on last year’s C grade. The detailed assessment marked the Government out of 10 in nine subject areas. The highest scores came in the categories of Waste and Circular Economy (7.5: down from 8.5 last year), Energy (7: a significant improvement from 4 last year) Buildings (7 – up from 6 last year) and Air Quality (7: same as last year). The lowest scoring categories were Agriculture and Forestry (4: same as last year), where the Government is now flirting with failure according to the judges, and Water and Marine (5: marginally up from 4.5 last year).

Commenting on the scores one of the judges, Paul Deane from UCC, said: “This year’s review gives us cause for hope but not a reason for celebration. Ireland’s greenhouse gas pollution has reduced marginally this year, but we are still massively addicted to fossil fuels. Many of the correct actions are being taken but just not at a speed that is quick enough or a scale that is large enough.”

The Chair of the assessment panel, Cara Augustenborg from UCD struck a hopeful note: “We are accustomed to hearing nothing but bad news when it comes to Ireland’s environmental record but taking a deep dive inside the Government’s work since 2020 provides clear evidence that progress is being made to improve Ireland’s environmental health in most areas.”

Diarmuid Torney, the judge from DCU added: “Overall delivery is slower than I would have liked to see approximately two thirds of the way through the Government’s term in office. Time is running short. There needs to be a real prioritisation of environment and climate over the remainder of the Government’s term.”

The experts for the first time identified some key commitments in the Programme for Government that are now in danger of not being achieved. These “critically endangered” commitments include the Government’s flagship climate commitment: on the current trajectory there is a real danger Ireland will not stay within the binding pollution limits of the first carbon budget and the sectoral emissions ceilings. Other “critically endangered” commitments include ones on agriculture and forestry, where the Government is still largely failing to achieve significant progress and drinking and waste water. Ireland’s water quality worsened in 2022 compared to 2021, with dangerous nitrate and phosphate concentrations in many of Ireland’s river sites, estuarine, and coastal water bodies.

This was the third year the independent expert assessment has been carried out and it has been gratifying to see the engagement from official stakeholders increase over time, as government departments have become keener to make sure the researchers and the judges are fully aware of any progress that has been made. It helps that the Report Card has generated significant media coverage each year.

But the specific areas of inadequate progress, the mixed bag of category scores and the “could do better” nature of an overall C+ grade show that civil society oversight and media scrutiny are not enough on their own to deliver the scale and pace of policy development and implementation we need to stay within the binding limits on pollution to 2025 and 2030 that have now been adopted by the Dáil, on a cross-party basis, under the 2021 climate law.

That is why it is very welcome that a crucial part of the climate law is about to come into action for the first time. In the coming weeks a Joint Oireachtas Committee will be summoning all the relevant Ministers to appear before it in under Section 14 of the Act. And not for a general update on progress and plans but to specifically respond to the EPA figures showing the state’s emissions are off track and to the recommendations from the Climate Change Advisory Council on how to close the emissions gap, sector by sector. The Ministers are obliged to outline the specific “corrective measures” they plan to take to reduce emissions fast enough to get back in line with the sectoral ceilings and the overall carbon budget limits.

Those Oireachtas hearings, chaired by Brian Leddin, are an essential exercise in parliamentary oversight and accountability that can push the next iteration of the Government’s Climate Action Plan, due before the end of the year, to be strong enough to get our emissions on track. As the scorecard judges could have put it this year: “A lot done, more to do.”